Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus (HRSV) is a common viral infection that primarily affects the respiratory system, particularly in infants and young children. HRSV is a leading cause of upper and lower respiratory tract infections (RTIs), which can progress to acute lower respiratory tract infections (ALRTIs). The virus gets its name from its ability to cause infected cells to merge, forming some large structures called Syncytia. These syncytia contribute to the severity of the illness by disrupting normal lung function. The virus spreads through objects (transmission through fomites) and by direct contact with infected secretions. Most of the infections result in mild and cold-like symptoms. Self-care measures are needed to relieve any discomfort.

Only 1 to 2% of the cases progress to more severe conditions, including pneumonia and bronchitis, often necessitating hospitalization. The heterogeneity of the ailments caused by HRSV relies on the host’s risk factors. These factors are preterm birth, chronic lung diseases, immunosuppression, and congenital heart diseases.

How common is Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus?

The virus causes a minimum of 3.4 million hospital admissions annually in the United States. HRSV is considered highly infectious. It can affect nearly 70% of babies before the first year of their life. It can also infect older adults. Worldwide, 200,000 deaths are estimated annually.1Durigon, E. L., Botosso, V. F., & de Oliveira, D. B. L. (2017). Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Biology, Epidemiology, and Control. Human Virology in Latin America: From Biology to Control, 235-254.

Increased healthcare costs and high hospitalization rates make HRSV infection a significant public health problem globally.2Nair, H., Nokes, D. J., Gessner, B. D., Dherani, M., Madhi, S. A., Singleton, R. J., … & Campbell, H. (2010). Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 375(9725), 1545-1555. Annual epidemics usually occur during winter in temperate climates and during the rainy season in tropical climates.3Bohmwald, K., Espinoza, J. A., Rey-Jurado, E., Gómez, R. S., González, P. A., Bueno, S. M., … & Kalergis, A. M. (2016, August). Human respiratory syncytial virus: infection and pathology. In Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (Vol. 37, No. 04, pp. 522-537). Thieme Medical Publishers.

Causes of Human Respiratory syncytial Infection

HRSV enters the body by the mouth, nose, or eyes. It can spread quickly through the air by infected respiratory droplets. Your children can become infected when someone with HRSV sneezes or coughs near you. It can also pass to other persons through direct contact, like shaking hands or kissing the face of a child with RSV. For four hours, this virus can live on solid and hard objects like toys, crib rails, and countertops. You can pick up the virus if you touch your eyes, mouth, or nose after touching the contaminated objects. The infected persons are highly contagious during their first week of infection. The virus can continue to spread in infants and immunosuppressed people even after the symptoms disappear. The virus can spread for up to four weeks.4Jain, H., Schweitzer, J. W., & Justice, N. A. (2023). Respiratory syncytial virus infection. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

Pathophysiology or Viral Infection Cycle

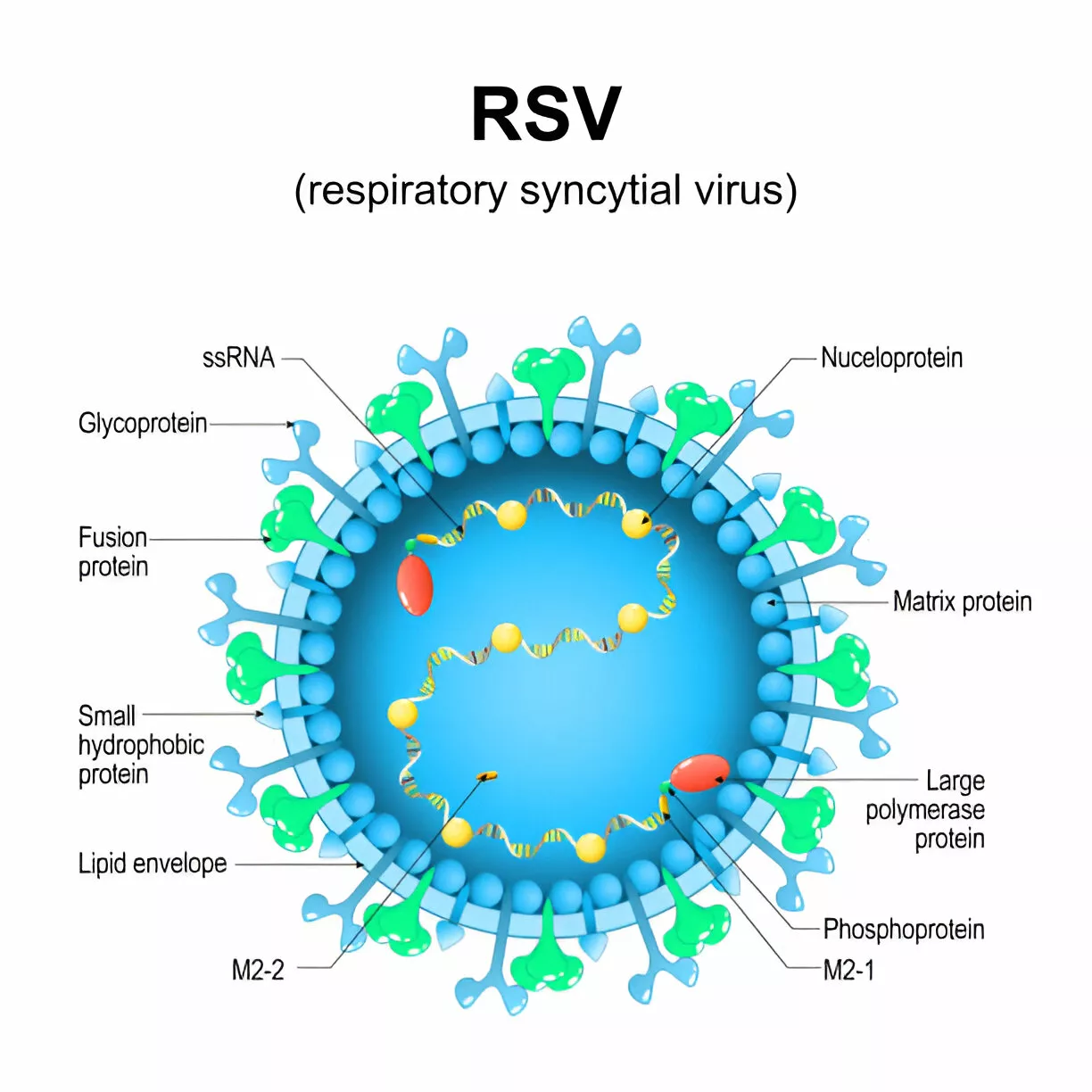

RSV is an enveloped, single-stranded, non-segmented RNA with negative polarity from the paramyxoviridae family. It possesses three integral membrane proteins. These are:

- A short hydrophobic protein (SH)

- The Fusion protein (F)

- The receptor attachment glycoprotein (G)

The SH protein forms a pentameric ion channel, while the F protein is responsible for fusion. The G protein is involved in the attachment of the host cell.5Gan, S. W., Tan, E., Lin, X., Yu, D., Wang, J., Tan, G. M. Y., … & Torres, J. (2012). The small hydrophobic protein of the human respiratory syncytial virus forms pentameric ion channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287(29), 24671-24689.

HRSV spreads from person to person through respiratory droplets. The incubation period after the inoculation ranges from two to eight days. The mean incubation period of HRSV is four to six days. This period depends on host factors like age. The stages of HRSV infection are:

Attachment & Entry

It rapidly spreads into the respiratory tract after entry and attachment with the conjunctival mucosa or nasopharyngeal mucosa. Here, it targets its favored growth medium. The medium is apical ciliated-epithelial cells. The virus binds to cellular receptors through RSV-G glycoprotein. After binding, it uses RSV-F fusion glycoprotein for fusion with the host’s cell membrane.

Replication

The virus inserts its nucleocapsid into the host cell and starts its intracellular replication. This stage is crucial for amplifying the viral load.

Assembly & Release

The newly formed RNA genomes and viral proteins are assembled into virions and packaged into vesicles. After this, the virions bud off from the host cell. This process allows the virus to escape into the extracellular matrix. There, it can infect other cells.

Immune Response

When RSV infects a human, it triggers the individual’s immune response. This response activates different types of immune cells, which can damage the cells lining the respiratory airways. Activation of cytotoxic T and humoral cells causes necrosis in respiratory epithelial cells. As these infected cells die, they can lead to downstream outcomes of small airway plugging or obstruction by cellular debris, DNA, and mucus accumulation in the area. In most severe cases, the blockage can extend to the tiny air sacs in the lungs (alveoli). Moreover, the damage can lead to problems like ciliary dysfunction, decreased lung compliance, impaired mucus clearance, and airway edema.6Schmidt, M. E., & Varga, S. M. (2020). Cytokines and CD8 T cell immunity during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Cytokine, 133, 154481.

Symptoms of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus

The signs and symptoms of the HRSV infection generally appear within four to six days after contact with the virus. The initial symptoms include:

- Dry cough

- Sore throat

- Headache

- Low-grade fever

- Congested or runny nose (rhinorrhea)

- Fever

- Respiratory distress

- Reduced appetite7Sweetman, L. L., Ng, Y. T., Butler, I. J., & Bodensteiner, J. B. (2005). Neurologic complications associated with respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatric neurology, 32(5), 307-310.

Infants are most severely affected. They exhibit these symptoms:

- Struggle to breathe (chest muscle and skin pull inward in each breath)

- Rapid breathing

- Shallow and short breathing

- Severe cough

- Lethargy (unusual tiredness)

- Poor feeding

- Irritability

In severe forms, HRSV infection can expand to the lower part of the respiratory tract. Hence, it causes bronchiolitis or pneumonia. The signs include:

- Severe alveolitis (inflammation of the lung alveoli)

- High fever

- Wheezing

- Severe cough

- Difficulty in breathing

- Rapid breathing

Most of the adults and children recover in one or two weeks. In contrast, some may experience repeated wheeziness. Life-threatening infections or severe infections can require a long hospital stay.8Navas, L., Wang, E., de Carvalho, V., & Robinson, J. (1992). Improved outcome of respiratory syncytial virus infection in a high-risk hospitalized population of Canadian children. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada. The Journal of Pediatrics, 121(3), 348-354.

Risk Factors & Complications

Children and adults can get an infection more than once. More commonly, children who attend childcare centers and whose siblings attend school are at a greater risk of exposure and infection.

People who are at increased risk of severe HRSV infection include:

- Premature infants (6 months old or younger)

- Children with chronic lung disorders

- Kids with congenital heart disorders

- Adults or infants with a weak immune system due to cancer treatments

- Adults with severe lung or heart disorders

- Children with neuromuscular disorders, including muscular dystrophy

- Older adults (more than 65 years old)

Complications of the HRSV include:

- Middle ear infection

- Asthma

- Repeated infection

Extrapulmonary complications that occur due to HRSV infection are the following:

- Myocarditis

- Pericardial infection

- Hyponatremia

- Hepatitis

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Seizures

- Apneas

- Encephalitis

- Status epilepticus

- Strabismus

- Encephalopathy9Welliver, R. C. (2003). Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. The Journal of Pediatrics, 143(5), 112-117.

Diagnosis of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus

The diagnosis of HRSV infection is usually clinical and does not require confirmatory tests. The diagnosis begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination. The healthcare provider will look at the symptoms and duration of the illness. He will ask for any potential exposure to the virus. Imaging or testing for HRSV is discouraged until its presence can alter medical decisions.

Specific tests for RSV infection help distinguish it from other disorders. These tests are recommended only in severe cases of high-risk patients. These tests are typically available in two commonly utilized methods.

Rapid Antigen Test:

The antigen test is an inexpensive, specific, and quick test. An antigen test requires nasal secretions for a specimen. This test confirms the presence of the virus. Nevertheless, the sensitivity of this test is only 80%.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR):

PCR is the most commonly used test. It identifies the HRSV RNA in the respiratory specimens. PCR testing is more useful in more severe cases and in those cases where symptoms are atypical. It has more sensitivity and specificity than antigen tests. The disadvantages of the PCR test include the requirement of the specialized equipment used to process it and the cost of the test.

Radiographic Imaging:

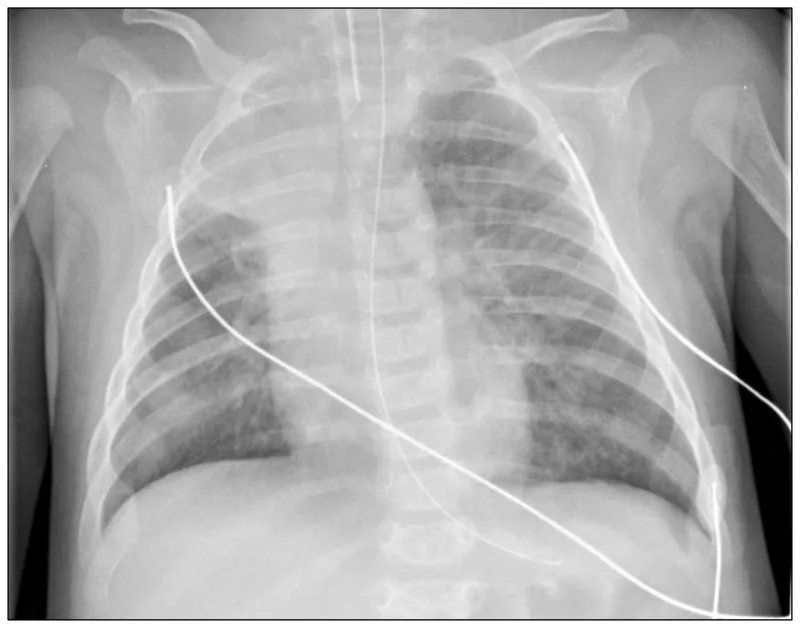

The radiological findings of the HRSV are similar to bronchiolitis.

Chest X-ray

The common chest X-ray findings of the infection include:

- Atelectasis, also known as lung collapse, is frequently observed in children with HRSV infections.

- Hyperinflation can also be present but does not strongly correlate with other clinical outcomes.

- Consolidation: consolidation patterns are also a common finding. It indicates areas of lung tissues filled with liquid instead of air.

The other common findings include peribronchial thickening, pneumothorax, and pleural effusion.10Jain, H., Schweitzer, J. W., & Justice, N. A. (2023). Respiratory syncytial virus infection. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

Treatment & Management of HRSV Infection

Treatment of HRSV falls into three major categories. These are supportive care, immune prophylaxis, and antiviral medications. The mainstream of HRSV cases requires no specific medical interference. Many treatments throughout history have been ineffective in curing the ailment. However, therapeutic interventions and vaccines for HRSV remain a target of deep scientific attention.

Supportive Care:

Supportive care is the mainstay of the treatment. It comprises lubrication and nasal suction to provide comfort from nasal congestion. Patients require assisted hydration in case of severe dehydration. The assistance can be through a nasogastric tube, by mouth, or intravenously. Patients require antipyretics for fever and oxygen for patients suffering from hypoxia. In case of respiratory failure, ventilator support is a must. Depending on the condition, mechanical ventilation, intubation, and high-flow nasal cannula can be done. Patients who are at risk for moderate to severe disorders require immediate hospitalization. Patients who require supplemental fluids and respiratory support also need intensive care at the hospital.

Pharmacological Management:

Bronchodilators

Sometimes used to relieve wheezing, though their efficacy in HRSV is variable.

Corticosteroids

Rarely recommended except in severe cases or underlying asthma.

Immune Prophylaxis

Immune prophylaxis for HRSV exists in the form of palivizumab. It is a humanized murine monoclonal antibody that has activity against the virus’s membrane fusion protein. Palivizumab should be given monthly during the RSV season, but it is somewhat expensive.

Antiviral Medications

Ribavirin is the antiviral medication approved against RSV in the United States. Ribavirin is a nucleoside analog, and administration is in aerosolized form. The use of this medicine in HRSV is still controversial. It is due to the expense, question of efficacy, and danger to exposure to healthcare providers. Usually, ribavirin is discouraged, but its use can be considered depending on the case.11Foolad, F., Aitken, S. L., Shigle, T. L., Prayag, A., Ghantoji, S., Ariza-Heredia, E., & Chemaly, R. F. (2019). Oral versus aerosolized ribavirin for treating respiratory syncytial virus infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 68(10), 1641-1649.

There are many other treatment modalities for HRSV. These comprise racemic epinephrine, antibiotics, hypertonic saline, albuterol, steroids, and physical chest therapy. However, experts do not recommend the repetitive use of these treatments at all.

Prevention

HRSV can infect anyone, but young infants, premature babies, and older adults with lung and heart diseases and weak immune systems are at high risk of severe infection.

There are two main preferences to help prevent young children from getting severe HRSV infection. One is the antibody product, and the other is the HRSV vaccine for pregnant people. You and your healthcare provider can discuss the best option to safeguard your child.

Beyfortus (Antibody Product Nirsevimab)

A monoclonal antibody for RSV is nirsevimab. Nirsevimab requires a single dose administration during the HRSV season or a month before. This product is for children younger than eight months and those born during or entering the first HRSV season. It is less expensive but can be more effective. The HRSV season typically lasts from November to March in the United States. The season varies in Hawaii, Florida, and other U.S. island territories. Rarely, when the child is not eligible for it, or nirsevimab is not available, palivizumab may be acceptable. However, the vaccine involves monthly shots during the whole HRSV season.

HRSV Vaccine during Pregnancy

Abrysvo is the FDA-approved vaccine for pregnant women to prevent HRSV in infants from birth to 6 months of age. Only a single dose shot of this vaccine is given from 32 weeks to 36 weeks of pregnancy from September to January.12Patel, D., Chawla, J., & Blavo, C. (2024). Use of the Abrysvo Vaccine in Pregnancy to Prevent Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Infants: A Review. Cureus, 16(8).

Vaccine for Older Adults

Arexvy and Abrysvo are two FDA-approved vaccines for adults aged 60 or older. These vaccines can prevent RSV infection in older adults, especially those with medical conditions. Talk to your healthcare professional about getting the RSV vaccine, mainly when you are at high risk of viral infection. Both vaccines are a single-dose shot.13Ruckwardt, T. J. (2023). The road to approved vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus. NPJ vaccines, 8(1), 138.

Precautions

Some precautions can help you to avoid RSV infection and its spread. These are:

- Cover your nose and mouth when you sneeze or cough.

- Limit your baby’s contact with people suffering from colds, coughs, or fevers.

- Teach your child to wash their hands after each activity. Tell them the importance of hand washing.

- Use your own glass when you or someone else is sick around you. Do not share drinking glasses with others.

- Ensure the doorknobs, handles, bathroom and kitchen countertops are clean.

- Throw used tissues in the trash box right away.

- Wash your child’s toys regularly, specifically when your child or his/her playmate is sick.

- Do not smoke next to your child. Babies exposed to tobacco have a high risk of getting RSV. Do not smoke inside your house or car.

- Stay away from others if you are sick.

- Take steps for cleaner air, such as purifying indoor air and bringing fresh outside air.

RSV versus HMPV

The Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV) is related to RSV, and both are members of the paramyxoviridae family. They share many clinical characteristics but differ in their epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options.

HMPV is a single-stranded RNA virus. Symptoms of HMPV can mirror those of RSV. It has a similar pattern of transmission as RSV. RSV is known to infect and spread more efficiently than HMPV. RSV primarily targets ciliated cells’ respiratory tracts and releases more effective viral particles, while HMPV is associated with the formation of filamentous extensions that facilitate cell-to-cell spread. HMPV tends to affect slightly older children than RSV. Both viruses circulate during similar seasonal periods, predominantly in early spring and winter. There are limited treatment options for both viruses. There is no vaccine for HMPV, and HSV can last longer than HMPV.14Adams, O., Weis, J., Jasinska, K., Vogel, M., & Tenenbaum, T. (2015). Comparison of human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and rhinovirus respiratory tract infections in young children admitted to hospital. Journal of Medical Virology, 87(2), 275-280.

Final Remarks

HRSV is a significant pathogen. It is a highly contagious virus that primarily affects respiratory infection globally, especially in infants and young children. It is a leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia. HRSV is responsible for a substantial burden on healthcare systems during seasonal outbreaks as it can lead to severe respiratory distress requiring hospitalization. Ongoing research into effective vaccine and antiviral treatments continues to be essential for reducing the burden of the virus. Understanding the nature of HRSV, its transmission mode, and its clinical manifestations is crucial to avoiding this viral infection and its impact on you. Timely diagnosis, effective clinical management, and robust preventive measures are essential for addressing the challenges posed by HRSV. Public health initiatives promoting good hygiene practices, such as avoiding close contact with infected people and frequent hand washing, can play a vital role in reducing the transmission of the virus. Get the vaccine if you are pregnant or above 65 years.

Refrences

- 1Durigon, E. L., Botosso, V. F., & de Oliveira, D. B. L. (2017). Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Biology, Epidemiology, and Control. Human Virology in Latin America: From Biology to Control, 235-254.

- 2Nair, H., Nokes, D. J., Gessner, B. D., Dherani, M., Madhi, S. A., Singleton, R. J., … & Campbell, H. (2010). Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 375(9725), 1545-1555.

- 3Bohmwald, K., Espinoza, J. A., Rey-Jurado, E., Gómez, R. S., González, P. A., Bueno, S. M., … & Kalergis, A. M. (2016, August). Human respiratory syncytial virus: infection and pathology. In Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (Vol. 37, No. 04, pp. 522-537). Thieme Medical Publishers.

- 4Jain, H., Schweitzer, J. W., & Justice, N. A. (2023). Respiratory syncytial virus infection. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- 5Gan, S. W., Tan, E., Lin, X., Yu, D., Wang, J., Tan, G. M. Y., … & Torres, J. (2012). The small hydrophobic protein of the human respiratory syncytial virus forms pentameric ion channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287(29), 24671-24689.

- 6Schmidt, M. E., & Varga, S. M. (2020). Cytokines and CD8 T cell immunity during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Cytokine, 133, 154481.

- 7Sweetman, L. L., Ng, Y. T., Butler, I. J., & Bodensteiner, J. B. (2005). Neurologic complications associated with respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatric neurology, 32(5), 307-310.

- 8Navas, L., Wang, E., de Carvalho, V., & Robinson, J. (1992). Improved outcome of respiratory syncytial virus infection in a high-risk hospitalized population of Canadian children. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada. The Journal of Pediatrics, 121(3), 348-354.

- 9Welliver, R. C. (2003). Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. The Journal of Pediatrics, 143(5), 112-117.

- 10Jain, H., Schweitzer, J. W., & Justice, N. A. (2023). Respiratory syncytial virus infection. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- 11Foolad, F., Aitken, S. L., Shigle, T. L., Prayag, A., Ghantoji, S., Ariza-Heredia, E., & Chemaly, R. F. (2019). Oral versus aerosolized ribavirin for treating respiratory syncytial virus infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 68(10), 1641-1649.

- 12Patel, D., Chawla, J., & Blavo, C. (2024). Use of the Abrysvo Vaccine in Pregnancy to Prevent Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Infants: A Review. Cureus, 16(8).

- 13Ruckwardt, T. J. (2023). The road to approved vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus. NPJ vaccines, 8(1), 138.

- 14Adams, O., Weis, J., Jasinska, K., Vogel, M., & Tenenbaum, T. (2015). Comparison of human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and rhinovirus respiratory tract infections in young children admitted to hospital. Journal of Medical Virology, 87(2), 275-280.