Infective endocarditis is a life-threatening disease mostly caused by bacterial infection of the lining of valves and chambers of the heart. It can also be caused by fungi. The symptoms are variable. Treatment involves antibiotic therapy and, sometimes, even surgery. Without treatment, the valves and chambers of the heart are damaged irreversibly.

What is Infective Endocarditis?

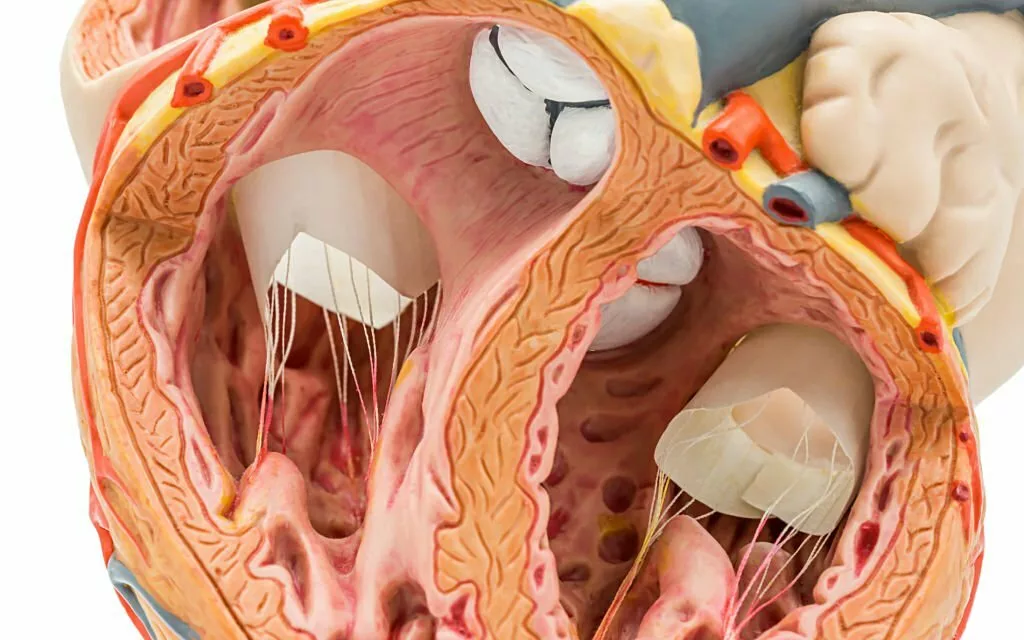

Endocarditis means “inflammation of endocardium.” Infective endocarditis refers to the inflammation of the heart’s inner lining, the endocardium, and often involves the valves that partition the heart’s four chambers. This condition is commonly bacterial in origin and exhibits a diverse range of symptoms and potential outcomes.1Yallowitz, A. W., & Decker, L. C. (2023). Infectious Endocarditis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

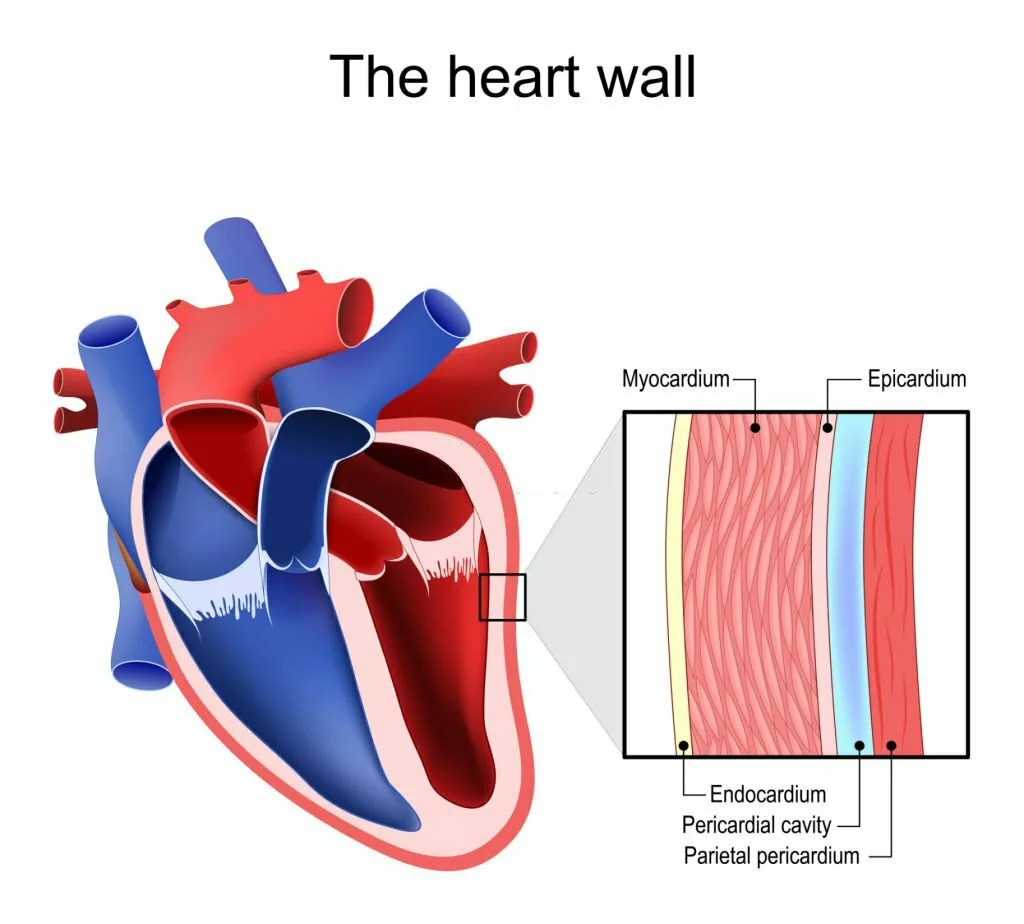

Layers of Heart and Endocarditis

The heart wall comprises three layers. The outermost layer is the epicardium, the middle layer, which contains most of the muscle, is the myocardium, and the innermost layer is the endocardium. The endocardium lines the chambers of the heart and its valves. Thus, infective endocarditis is the term for the inflammation and infection of the innermost endocardium layer. Since the endocardium is in direct contact with the blood present in the heart, bacteria and other organisms that are present in the blood can cause infection.

Causes of Infective Endocarditis

The predominant cause of infective endocarditis is bacterial infection. Most cases of infectious endocarditis result from infections caused by gram-positive bacteria, namely streptococci, staphylococci, and enterococci. Collectively, these three groups contribute to almost 90% of all cases, with Staphylococcus aureus accounting for approximately 30% of cases, specifically in developed countries.2Barnett R. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016 Sep 17;388(10050):1148.

These bacteria typically reside in various areas of our body, including the skin, mouth, gut, respiratory system, and urinary tract, as a part of the body’s normal flora. Any activity that releases these bacteria into the bloodstream, such as routine actions like brushing teeth, eating, or flossing, can potentially lead to infective endocarditis. In some cases, it may also arise due to an underlying health condition.

Once the bacteria is in the blood, it is circulated to the heart. Healthy heart valves and endocardium are very resistant to infection, so infective endocarditis is less likely.

If diseases like rheumatic fever have already damaged the valves or if prosthetic valves are in place, the risk of developing infective endocarditis increases. Other organisms, such as fungi, can also cause infective endocarditis. Candida albicans is the most common cause of non-bacterial infective endocarditis3Morelli, M. K., Veve, M. P., Lorson, W., & Shorman, M. A. (2021). Candida spp. Infective endocarditis: Characteristics and outcomes of twenty patients with a focus on injection drug use as a predisposing risk factor. Mycoses, 64(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13200.

Risk Factors of Infective Endocarditis?

Endocarditis is more common in males than in females4Elamragy, A. A., Meshaal, M. S., El-Kholy, A. A., & Rizk, H. H. (2020). Gender differences in clinical features and complications of infective endocarditis: 11-year experience of a single institute in Egypt. The Egyptian heart journal (EHJ): official bulletin of the Egyptian Society of Cardiology, 72(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-020-0039-6. People who are older than 60 make up almost 25% of diagnosed cases of infective endocarditis. The following conditions also increase the risk of infective endocarditis in people:

- Diseases of heart valves like Rheumatic fever, mitral valve prolapse, and aortic valve sclerosis.

- Prosthetic valves, i.e., artificial valves in the heart after surgery

- Birth defects of the heart

- A previous episode of bacterial endocarditis

- Having cardiac devices like a Pacemaker

- Suppressed immune system functioning in diseases like HIV

- Drug abuse

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Dental procedures

- Insertion of catheters or needles

Signs and Symptoms of Infective Endocarditis

The symptoms of endocarditis are as follows:

- Fever

- Night sweats or chills

- Rash

- Pain and tenderness

- Sore throat

- Weightloss

- Poor appetite

- Muscle and joint pains

- Nausea, vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Cough

- Nasal congestion

- Headache

Clinical Signs:

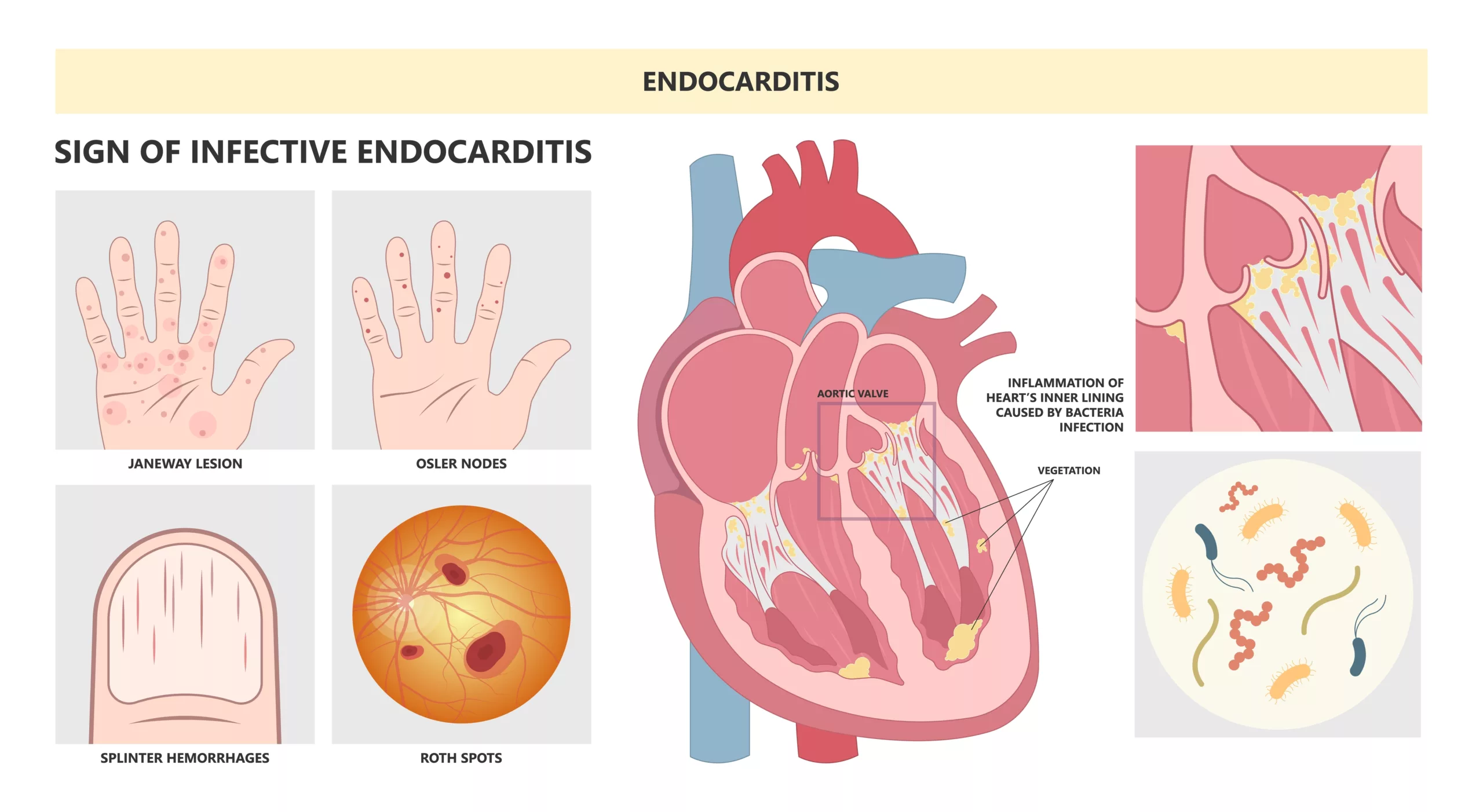

Some clinical signs consistent with Infective endocarditis include the following:

Heart Murmur

An abnormal sound in the heart is heard during a physical examination.

Osler’s Nodes

Painful, tender nodules in the pads of fingers or toes.

Janeway Lesions

Non-tender, small, red, or hemorrhagic spots on the palms or soles of the feet. Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes are found in less than 10% of cases of infective endocarditis. In the pre-antibiotic era, they were presenting 40 to 50% of the cases.5Hirai T, Koster M. Osler’s nodes, Janeway lesions, and splinter hemorrhages. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Sep 6;2013:bcr2013009759. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009759. PMID: 24014557; PMCID: PMC3794095.

Roth Spots

Retinal hemorrhages with a white or pale center and a hemorrhagic border.

Petechiae

Small red or purple spots on the skin, especially in the conjunctiva (whites of the eyes) or inside the mouth.

Clubbing of Fingers

Changes in the shape of the fingertips or nails.

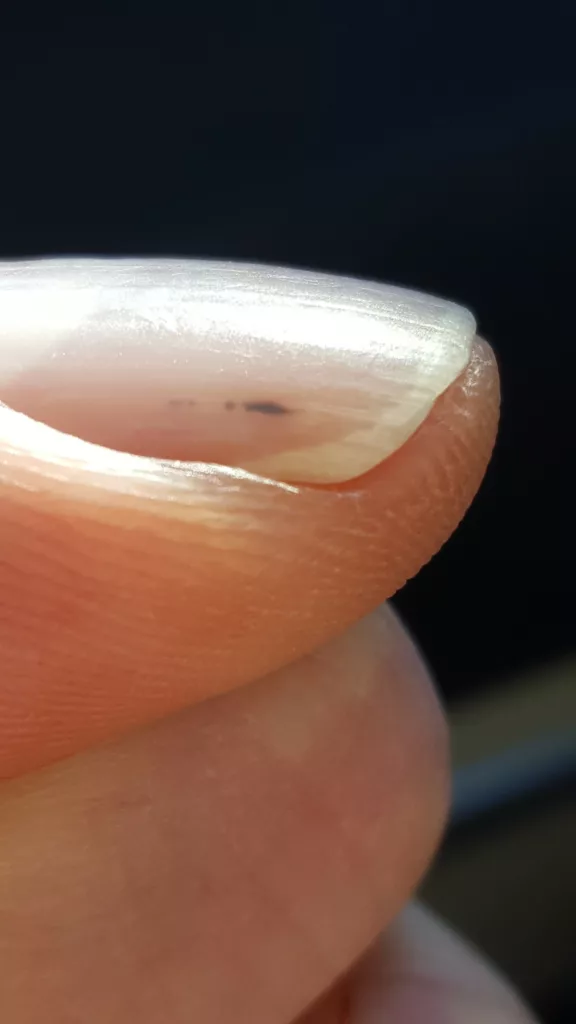

Splinter Hemorrhages

The presence of slender red streaks beneath the fingernails.

Complications & Risks

The symptoms of infective endocarditis, dependent on the causative organism, can lead to various complications.

Vegetation Formation

Bacteria lodged in the heart valves have the potential to generate sizable growths, referred to as vegetation. These vegetations are composed of bacterial clusters and blood clots. Their presence within the heart can lead to serious complications.

Risk of Emboli

One critical risk associated with these vegetation is their ability to dislodge and travel through the bloodstream as emboli. As they move through the blood vessels, they have the potential to cause blockages in vital areas.

Neurological Complications

If an embolus obstructs blood vessels supplying the brain, it can result in a stroke. The occurrence of a stroke is a serious and potentially life-altering complication of infective endocarditis, as the disruption of blood flow to the brain can lead to various neurological symptoms and, in severe cases, long-term consequences or even be fatal.6Merkler, A. E., Chu, S. Y., Lerario, M. P., Navi, B. B., & Kamel, H. (2015). Temporal relationship between infective endocarditis and stroke. Neurology, 85(6), 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001835

Heart & Organ Involvement

If the blood vessels supplying the heart are blocked, it can result in a heart attack.7Calero-Núñez, S., Ferrer Bleda, V., Corbí-Pascual, M., Córdoba-Soriano, J. G., Fuentes-Manso, R., Tercero-Martínez, A., Jiménez-Mazuecos, J., & Barrionuevo Sánchez, M. I. (2018). Myocardial infarction associated with infective endocarditis: a case series. European Heart Journal. Case reports, 2(1), yty032. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/yty032

Heart valve perforation and subsequent leakage can occur, along with potential arterial infections. Additionally, the condition may affect various organs, such as the lungs, kidneys, and spleen. The involvement of organs may lead to Septic Shock8Parra, J. A., Hernández, L., Muñoz, P., Blanco, G., Rodríguez-Álvarez, R., Vilar, D. R., de Alarcón, A., Goenaga, M. A., Moreno, M., Fariñas, M. C., & Spanish Collaboration on Endocarditis-Grupo de Apoyo al Manejo de la Endocarditis Infecciosa en España (GAMES) (2018). Detection of spleen, kidney, and liver infarcts by abdominal computed tomography does not affect the outcome in patients with left-side infective endocarditis. Medicine, 97(33), e11952. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011952. Thus, infective endocarditis can have several consequences, which can be destructive.

Types of Infective Endocarditis

There are two major types of bacterial endocarditis9Vilcant, V., & Hai, O. (2023). Bacterial Endocarditis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing..

Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis

It develops slowly over a period of weeks and months. This type of endocarditis is most commonly caused by Streptococcus Viridians. It affects the already damaged heart valves. Moreover, it is often accompanied by high-grade fever. It does not destroy the valves completely. However, its treatment lies in antibiotic therapy only.

Acute Endocarditis

It develops suddenly and becomes life-threatening if not treated promptly. Acute endocarditis is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus. It affects the heart of illegal drug abusers. The fever is usually low-grade. It has the tendency to destroy the heart completely. It requires antibiotic therapy as well as surgery.

Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis

A doctor may suspect infective endocarditis if the following features are present in clinical examination:

- Fever

- Murmur in heart

- Reddish spots on palms, soles, fingers, and toes.

- Hemorrhages in the nail bed.

- Roth spot in the retina

- A history of drug abuse

- A history of dental, surgical, or medical procedures.

In diagnosing infective endocarditis, a comprehensive evaluation is necessary due to its nonspecific symptoms. Differential diagnosis is crucial to rule out potentially life-threatening cardiopulmonary conditions such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia in patients with chest pain or dyspnea. Rapid assessment following established protocols is required for patients presenting with severe sepsis. For those with chest pain or trouble breathing, doctors might start with a simple heart test called an electrocardiogram (ECG) to check for heart problems. In endocarditis, this test usually looks normal.

Laboratory Workup:

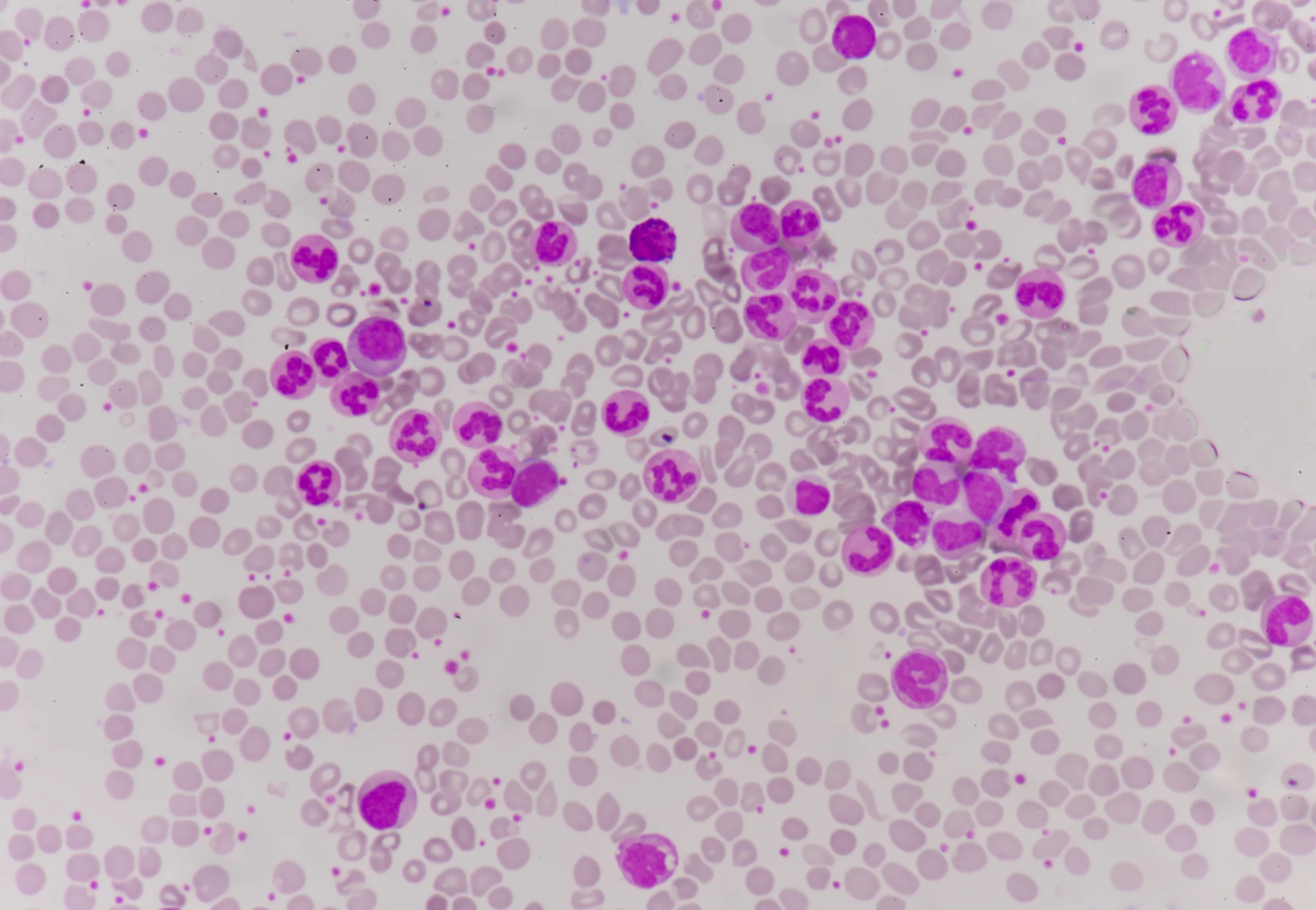

- Complete Blood Count: Often reveals leukocytosis, an indicator of an infectious process. Subacute cases may display normocytic anemia.

- Inflammatory Markers: ESR and CRP elevation is seen in about 60% of cases.10Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG, Bayer AS, Karchmer AW, Olaison L, Pappas PA, Moreillon P, Chambers ST, Chu VH, Falcó V, Holland DJ, Jones P, Klein JL, Raymond NJ, Read KM, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Wang A, Woods CW, Cabell CH., International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) Investigators. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 09;169(5):463-73.

Imaging Studies:

- Transesophageal electrocardiogram: It shows lesions on the heart valves or supporting structures. In a transesophageal echocardiogram, the physician or trained staff passes the ultrasound probe into the esophagus through the mouth. A transthoracic echocardiogram is another option. It is performed by placing the probe on the chest wall. Some conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, past chest surgeries, being overweight, or having artificial heart valves might make it hard to see the heart properly using the TTE. Although Transesophageal echocardiogram is invasive, it provides accurate results.

- Contrast-enhanced CT scans: CT angiograms may be needed to investigate pulmonary issues or arterial embolization.

Blood Culture:

Blood cultures are crucial in diagnosing infective endocarditis as they detect live bacteria and their susceptibility. To ensure accuracy, at least three sets of blood cultures, taken at 30-minute intervals from a peripheral vein, are needed. It’s important to avoid using central venous catheters to reduce contamination risks. These cultures should be collected before starting antibiotics. In infective endocarditis, continuous bacteremia leads to consistent positive blood cultures, so even one positive culture should be viewed carefully for diagnosis. It’s important to inform the lab of the suspected infection during sample collection.

However, the blood culture may not always be positive. It is because of the possibility that the person has taken antibiotics before giving the blood sample, which reduces the number of bacteria enough that they become undetectable. Another explanation can be that endocarditis is not because of any organism or infection. This condition is called non-infective endocarditis.

Dukes Criteria for Infective Endocarditis

The Duke criterion serves as a diagnostic guideline for identifying infective endocarditis based on a combination of major and minor criteria. These criteria incorporate clinical, echocardiographic, and biological indicators, along with blood culture and serology outcomes.

The diagnosis of infective endocarditis follows the Duke criteria, involving a set of major and minor criteria.11Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 21;36(44):3075-3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. Epub 2015 Aug 29. PMID: 26320109. To establish a diagnosis:

- Two major and one minor criterion or

- One major and three minor criteria or

- Five minor criteria are required.

Major & Minor Criteria for Infective Endocarditis Diagnosis

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

– Positive blood cultures for typical microorganisms:

|

– Predisposing heart conditions or intravenous drug use |

| – Evidence of endocardial involvement | – Fever (≥38°C) |

| – Positive echocardiogram for IE | – Vascular phenomena: arterial emboli, pulmonary infarcts, etc. |

| – Immunologic phenomena: Osler nodes, Roth spots, and more | |

| – Microbiologic evidence: Positive blood culture but not meeting a major criterion as noted above or serologic evidence of active infection with an organism consistent with IE. |

Non-infective Endocarditis

Non-infective endocarditis is characterized by the presence of vegetation on the heart valves. The key distinction between infective and non-infective endocarditis lies in the absence of microorganisms in the latter. Symptoms manifest only when the vegetation dislodges, forming emboli that can obstruct arteries throughout the body. Diagnosis typically involves an echocardiogram and blood cultures. Also known as nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), the primary treatment for this condition is anticoagulant therapy.12van der Burg, M. C., Balder, J. W., van den Brand, J. J. G., van Gulik, S., & Fiolet, A. T. L. (2021). Niet-bacteriële trombotische endocarditis [Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde, 165, D5816.

Treatment of Infective Endocarditis

The following treatments can be recommended by the doctor for the patient with infective endocarditis:

Medical Therapy

The mainstay treatment of infective endocarditis is antibiotic therapy. Blood cultures single out the organism causing the infection. It helps in giving targeted antibiotics to the organism. Initially, broad-spectrum antibiotics are often administered to provide coverage for a wide range of organisms. Typically, they administer antibiotics intravenously for a minimum of 6 weeks to ensure a complete recovery from the infection. The physician monitors the symptoms to see the effectiveness of therapy. Repeated blood cultures are also done.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is frequently necessary in cases of infective endocarditis involving vegetation, heart valve damage, or infected prosthetic valves. Infective endocarditis surgery aims to control infection, prevent or treat complications related to heart valve damage, and replace or reconstruct damaged tissue. The timing of surgery varies based on the severity of the infection, with urgent procedures often required for critical conditions. Factors prompting urgent surgery include issues like abscesses around the aortic valve, extensive valve damage from certain fungal infections, heart failure resulting from valve problems, large vegetations prone to dislodging, mitral valve stenosis, and valvular regurgitation. Surgical procedures may involve debridement, valve repair, reconstruction using pericardial tissue, or valve replacement with artificial ones in severely damaged cases.

Certain individuals may not be suitable candidates for surgery due to factors such as chronic medical issues, age-related frailty, or compromised immune systems. Healthcare providers follow established guidelines and use assessments, including blood tests and imaging, to determine the need for surgery and plan appropriate procedures based on the type and severity of heart valve damage.

Prevention of Infective Endocarditis

The best way to prevent infective endocarditis is to maintain good oral hygiene because the mouth is the major source of the spread of infection to the blood. 13Lockhart, P. B., Chu, V., Zhao, J., Gohs, F., Thornhill, M. H., Pihlstrom, B., Mougeot, F. B., Rose, G. A., Sun, Y. P., Napenas, J., Munz, S., Farrehi, P. M., Sollecito, T., Sankar, V., & O’Gara, P. T. (2023). Oral hygiene and infective endocarditis: a case-control study. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 136(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2023.02.020 As a result, it is advisable to brush and floss regularly and to seek dental care every six months from a specialist.

It is especially important for high-risk individuals. Preventing infection by healthy habits is better than taking prophylactic antibiotics.

To sum it up, Infective endocarditis is the infection of the endocardium, commonly caused by bacteria and, sometimes, fungi. It commonly occurs in individuals with damaged heart valves or artificial valves. It is also common in individuals with congenital heart diseases. The mainstay treatment is antibiotic therapy for six weeks. However, if not treated promptly, it can be life-threatening.

Refrences

- 1Yallowitz, A. W., & Decker, L. C. (2023). Infectious Endocarditis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- 2Barnett R. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016 Sep 17;388(10050):1148.

- 3Morelli, M. K., Veve, M. P., Lorson, W., & Shorman, M. A. (2021). Candida spp. Infective endocarditis: Characteristics and outcomes of twenty patients with a focus on injection drug use as a predisposing risk factor. Mycoses, 64(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13200

- 4Elamragy, A. A., Meshaal, M. S., El-Kholy, A. A., & Rizk, H. H. (2020). Gender differences in clinical features and complications of infective endocarditis: 11-year experience of a single institute in Egypt. The Egyptian heart journal (EHJ): official bulletin of the Egyptian Society of Cardiology, 72(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-020-0039-6

- 5Hirai T, Koster M. Osler’s nodes, Janeway lesions, and splinter hemorrhages. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Sep 6;2013:bcr2013009759. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009759. PMID: 24014557; PMCID: PMC3794095.

- 6Merkler, A. E., Chu, S. Y., Lerario, M. P., Navi, B. B., & Kamel, H. (2015). Temporal relationship between infective endocarditis and stroke. Neurology, 85(6), 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001835

- 7Calero-Núñez, S., Ferrer Bleda, V., Corbí-Pascual, M., Córdoba-Soriano, J. G., Fuentes-Manso, R., Tercero-Martínez, A., Jiménez-Mazuecos, J., & Barrionuevo Sánchez, M. I. (2018). Myocardial infarction associated with infective endocarditis: a case series. European Heart Journal. Case reports, 2(1), yty032. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/yty032

- 8Parra, J. A., Hernández, L., Muñoz, P., Blanco, G., Rodríguez-Álvarez, R., Vilar, D. R., de Alarcón, A., Goenaga, M. A., Moreno, M., Fariñas, M. C., & Spanish Collaboration on Endocarditis-Grupo de Apoyo al Manejo de la Endocarditis Infecciosa en España (GAMES) (2018). Detection of spleen, kidney, and liver infarcts by abdominal computed tomography does not affect the outcome in patients with left-side infective endocarditis. Medicine, 97(33), e11952. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011952

- 9Vilcant, V., & Hai, O. (2023). Bacterial Endocarditis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- 10Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG, Bayer AS, Karchmer AW, Olaison L, Pappas PA, Moreillon P, Chambers ST, Chu VH, Falcó V, Holland DJ, Jones P, Klein JL, Raymond NJ, Read KM, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Wang A, Woods CW, Cabell CH., International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS) Investigators. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 09;169(5):463-73.

- 11Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 21;36(44):3075-3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. Epub 2015 Aug 29. PMID: 26320109.

- 12van der Burg, M. C., Balder, J. W., van den Brand, J. J. G., van Gulik, S., & Fiolet, A. T. L. (2021). Niet-bacteriële trombotische endocarditis [Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde, 165, D5816.

- 13Lockhart, P. B., Chu, V., Zhao, J., Gohs, F., Thornhill, M. H., Pihlstrom, B., Mougeot, F. B., Rose, G. A., Sun, Y. P., Napenas, J., Munz, S., Farrehi, P. M., Sollecito, T., Sankar, V., & O’Gara, P. T. (2023). Oral hygiene and infective endocarditis: a case-control study. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology, 136(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2023.02.020