Engraftment Syndrome (ES) is a potentially serious post-transplant complication that occurs during the early phase of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). It can happen in both autologous stem cell transplant (where your own cells are used) and allogeneic stem cell transplant (where the donor’s cells are used). This phase usually corresponds with the initial rise in neutrophil counts following their depletion from high-dose chemotherapy or radiation. This may be an indication that the transplant is working, but at times it may cause an extreme inflammatory reaction within the body.1Spitzer TR. (2001). Engraftment syndrome: double-edged sword of hematopoietic cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 27(1), 1–2.

Engraftment syndrome is a non-infectious condition that is caused by a surge of pro-inflammatory cytokines (or chemical messengers that support communication among the cells during the immune response). The outcome is fever, skin rash after transplant, pulmonary edema, gastrointestinal symptoms, liver enzymes abnormalities, kidney dysfunction, and even weight gain due to the capillary leak syndrome

In contrast to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), in ES, the immune cells of the donor do not attack the host. Rather, it is better described as friendly fire (an overreaction of your own body to the engraftment process).

This condition can be seen in both autologous and allogeneic transplants, though it’s reported more frequently in autologous settings, particularly among patients with multiple myeloma or lymphoma. It is also frequently underdiagnosed, largely because its symptoms overlap with other post-transplant complications, especially infections and GVHD.

Why Does Engraftment Syndrome Happen?

The new cells begin to settle into the bone marrow and start producing healthy blood cells after a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). While this is a positive sign of engraftment, it can also lead to immunological imbalance. As the immune system reboots, it may launch an exaggerated inflammatory response, releasing a surge of cytokines.2Carreras E, Díaz-Ricart M. (2011). The role of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of HSCT-associated syndromes. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 46(2), 149-156.

Why would your body do that? The new cells are being introduced into an environment previously damaged by chemotherapy or radiation. The immune system detects changes and tries to “fix” what it perceives as inflammation or danger, even though the transplant is supposed to help. The following contributing factors are involved:

- Fast recovery of neutrophils, which is related to granulocyte-CSF administration.

- Prior infection or tissue damage is a trigger for the immune system to cause an excessive response.

- Some transplant regimes, particularly those involving peripheral blood stem cells or HLA-mismatched donors, carry a higher risk of triggering this syndrome.

Timing and Onset of Engraftment Syndrome

The time of symptoms is an important hint in the case of engraftment syndrome. ES is generally observed at the peri-engraftment phase, and this normally occurs between the 7th and the 14th days after the transplantation, as the neutrophils of the patient are returning to normal levels (ANC > 500/l).3Maiolino A, Biasoli I, Lima J, Portugal R, Pulcheri W. (2003). Engraftment syndrome following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Haematol, 110(4), 190–195.

Throughout the period, the immune system is gearing up, and inflammation markers are at their highest. It occurs when the patients are crossing the aplastic phase (where the blood counts are very low) and enter the engraftment period. This timeline helps distinguish ES from other transplant-related complications. For instance:

- Infections can happen anytime, but often earlier or later

- In allogeneic transplants, GVHD usually occurs after day 20

Knowing this window enables the doctors and caregivers to recognize oncoming signs of ES and, hence, quickly respond to them, which is crucial in subsequent complication reduction and better recovery.

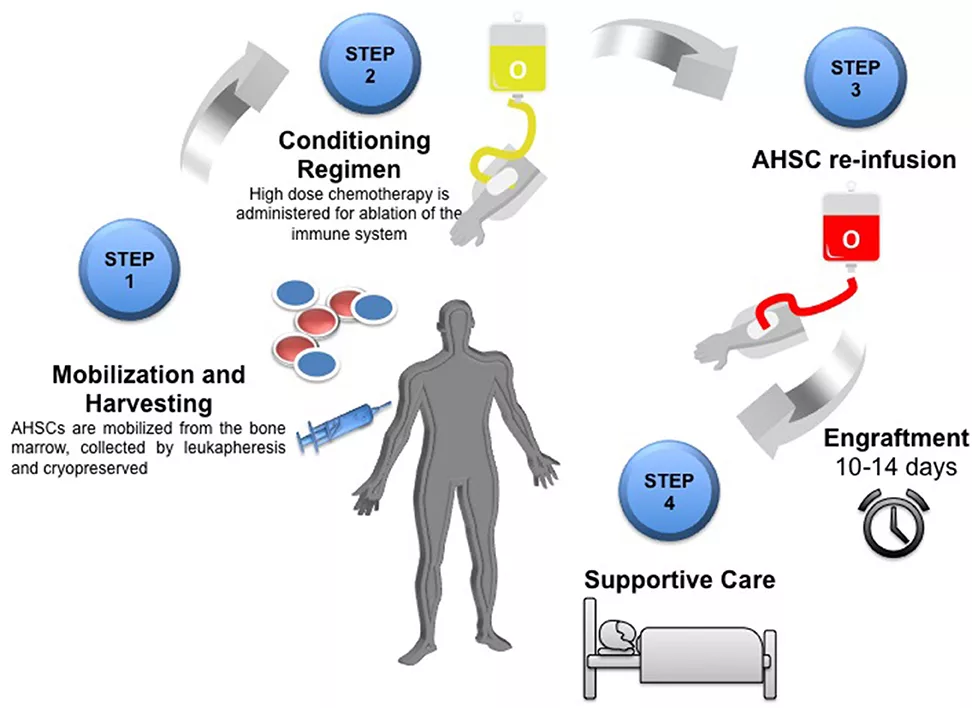

Image Source: Adapted from Achiron, A., & Doniger, G. M. (2020). Autologous Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Neurological Diseases – A Review. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 556141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.556141

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Symptoms of Engraftment Syndrome

Engraftment syndrome typically presents with a constellation of symptoms that flare up rapidly over 24–48 hours. These include:4Takanashi M, Arai S, Nakamura Y, Kanda Y. (2003). Symptoms and risk factors of engraftment syndrome in autologous and allogeneic transplantation. Int J Hematol, 78(4), 386–392.

- Fever above 38°C (100.4°F), often without infection

- Weight gain after transplant, often 2.5 percent or higher because of fluid retention.

- Patchy or generalized rash, usually on the trunk or the limbs

- Symptoms of the lungs, e.g., lack of oxygen or shortness of breath

- It can be associated with capillary leak and is characterized by hypotension

- Abnormal liver functions or a slight rise in bilirubin levels

- Gastrointestinal symptoms post‑transplant (e.g., diarrhea)

Severity & Progression of Symptoms:

Engraftment syndrome can also be quite severe. It may present with mild and self-limiting symptoms. In other cases, they rapidly develop into life-threatening symptoms such as:5Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, Kim S, Seol M, Lee YS. (2005). Engraftment syndrome after stem cell transplantation: Clinical manifestations and risk factors. Leuk Res, 29(3), 277–282.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Multi-organ failure

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

The onset of mild fever might develop into respiratory failure within a few hours unless detected. This is why it is common to treat ES with proactive ICU-level monitoring, especially in high-risk patients.

Factors influencing severity include:

- Speed of neutrophil recovery

- Conditioning regimen intensity

- Type of stem cell source (peripheral blood stem cells carry a higher risk)

How Long Do Symptoms Last?

Overall, the ES symptoms are acute and do not last long, more precisely, 2 to 5 days, with the appropriate intervention. A substantial improvement with corticosteroids is usually seen within 24 hours. Symptoms can, however, continue or be aggravated without prompt treatment, which will result in organ damage.6Chaudhry MS, et al. (2016). Engraftment syndrome: A unique post-transplant complication. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther, 9(2), 66–71. The recovery schedules depend on:

- The diagnosis speed

- Steroid responsiveness

- Presence of secondary issues such as infections or organ dysfunction

Most of the patients recover to their normal levels quite fast when the ES subsides. In case it is treated early and aggressively, long-lasting effects are unlikely.

Diagnosis of Engraftment Syndrome

Clinical Criteria for Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of ES is largely clinical, based on the combination of characteristic signs and their timing. The most popular criterion belongs to Spitzer (2001,) who suggests the following:7Spitzer TR. (2001). Engraftment syndrome: an increasingly recognized transplant complication. Bone Marrow Transplant, 27(9), 893–898.

- Major criteria:

- Non-infectious fever

- Skin rash

- Hypoxia or Pulmonary infiltrates

- Minor criteria:

- Weight gain (>2.5%)

- Liver dysfunction

- Renal dysfunction

- Transient encephalopathy

Only ≥3 major criteria or 2 major + 1 minor during the engraftment window (usually days 7–14) are needed to make a diagnosis. Importantly, infectious causes must be ruled out first.

Diagnostic Tests & Biomarkers:

ES does not have any specific laboratory tests, but supportive results include:8Jacobsohn DA, Vogelsang GB. (2007). Acute graft-versus-host disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2, 35.

- Increased C-reactive protein (CRP) or ferritin

- The raised level of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-alpha)

- Abnormal liver enzymes

- Normal cultures (to exclude infection)

Blood tests help confirm the inflammatory nature and rule out other causes. Biomarkers are an area of ongoing research for earlier, more accurate detection.

Role of Imaging & Other Tools:

Imaging can help us to assess the extent of organ involvement:9Schuster MG, Cleveland J, Gill VJ. (2004). Diagnostic use of imaging in transplant complications. Curr Opin Oncol, 16(2), 121–125.

- Chest X-rays or CT scans show if there are pulmonary infiltrates or fluid buildup in the lungs.

- Ultrasound can detect fluid in the abdomen or around the lungs.

- MRI is a good tool if you have neurological symptoms. MRI can help rule out CNS infections.

The combination of clinical judgment with these tools differentiates ES from conditions like pneumonia or GVHD and guides the treatment approach.

Engraftment Syndrome vs Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD)

Key Differences Between Engraftment Syndrome & GVHD:

While both engraftment syndrome and GVHD involve inflammatory responses post-transplant, they are fundamentally different conditions with distinct causes, timelines, and treatments.10Carreras E, et al. (2011). Distinguishing engraftment syndrome from GVHD: importance of early diagnostic markers. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 46(4), 469–475.

| Feature | Engraftment Syndrome | GVHD |

| Cause | Cytokine storm during neutrophil recovery | Donor T-cells attacking the recipient tissues |

| Onset | Day 7–14 post-transplant | Usually, after day 20 |

| Affects | Skin, lungs, GI tract (transiently) | Skin, liver, GI tract (can be chronic) |

| Response to steroids | Rapid and dramatic | Variable, often prolonged treatment |

| Common in | Both autologous and allogeneic transplants | Only in allogeneic transplants |

Understanding these differences can help avoid misdiagnosis and ensure patients get the right treatment at the right time.

Overlapping Symptoms & Diagnostic Challenges:

Despite their differences, ES and GVHD often present with similar symptoms: fever, rash, fluid retention, and gastrointestinal distress. This overlap makes diagnosis tricky, especially when trying to quickly determine the cause of a patient’s deterioration post-transplant.11Atkins HL, et al. (2003). Engraftment syndrome: diagnostic dilemmas in early post-transplant care. J Clin Oncol, 21(6), 1115–1120.

Doctors often use a process of elimination, combined with timing and response to treatment. If a patient shows improvement with steroids within 24–48 hours, ES is more likely. Lack of improvement might indicate GVHD or another condition. Other diagnostic pitfalls include:

- Fever in neutropenic patients, which could be infection or ES

- Skin rashes, which may look identical in GVHD and ES

- Respiratory issues, possibly caused by ES-related capillary leakage or infections

Distinguishing ES from GVHD early is not just academic—it saves lives.

Treatment Options for Engraftment Syndrome

Corticosteroid Therapy:

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for managing engraftment syndrome. The methylprednisolone is the most frequently used steroid, which is usually given in a dose of 1–2 mg/kg/day.12Saliba RM, et al. (2002). Corticosteroids for the treatment of engraftment syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant, 30(6), 425–429.

The speed of response is one of the most promising factors about corticosteroid therapy. Many signs start to improve 24 to 48 hours after the start of steroid treatment, such as fever, rash, and respiratory distress.

Upon control of the symptoms, tapering of steroids usually commences at day 3 to 5 on clinical improvement. But this tapering needs to be closely monitored to prevent rebound inflammation or side effects of steroids, e.g., hyperglycemia, higher risk of infections, or mood swings.

Supportive & Adjunct Therapies:

Along with steroids, supportive care may include:13Pérez-Simón JA, et al. (2005). Supportive therapy in engraftment syndrome: current practice. Haematologica, 90(12), 1600–1604.

- Diuretics are used for fluid overload

- Oxygen therapy or ventilation if the patient is in respiratory distress

- Antibiotics (empirically) until the infection is ruled out

- Correction of Electrolyte imbalance and hydration

Some centers use tocilizumab which is a monoclonal antibody. It can reduce a cytokine, interlukine 6 (IL-6), involved in causing inflammation. However, this remains experimental.

Monitoring Response and Changing Treatment Plans:

After initiating treatment, patients are closely observed for:14Bajwa RPS, et al. (2016). Management of Engraftment Syndrome: Experience from a Tertiary Care Center. Transplant Proc, 48(10), 3550–3554.

- Improvement in fever and rash

- Stabilization of oxygen levels

- Decrease in inflammatory parameters

When symptoms continue after 48 hours or when they are not resolved, the clinicians can:

- Re-evaluate for GVHD or infection

- A dose adjustment for steroids or the use of second-line agents

- Admit patients to the ICU, where they can receive intensive support

Further follow-up should be ensured for a long period to prevent organ damage or steroid complications.

Prognosis of Engraftment Syndrome

Is Engraftment Syndrome Fatal?

Engraftment syndrome (ES) can be alarming, especially as symptoms often develop rapidly. Understandably, one of the first questions patients and caregivers ask is: Can it be fatal?

The answer is yes, but with important context. While ES can become life-threatening in severe cases, the majority of patients recover fully when the condition is recognized early and treated promptly.15Fuji S, et al. (2012). Clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis after engraftment syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 18(12), 1818–1825.

The majority of individuals have a full recovery, especially if they are treated at an early stage using corticosteroids. Nevertheless, in other situations, the syndrome may develop quickly and result in multi-organ dysfunction, and there is a great danger of death when such a patient is not hospitalized in an ICU.

Long-Term Prognosis & Recovery:

Here’s the good news: once engraftment syndrome resolves, it typically doesn’t come back. That makes it a very different beast from conditions like chronic GVHD or certain infections that can linger or recur.16Armand P, et al. (2007). Prognostic implications of engraftment syndrome in stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant, 40(5), 433–439.

The long-term outlook depends on a few factors:

- How early the condition was treated

- Whether there was organ involvement (lungs, kidneys, liver)

- Overall transplant success and absence of other complications

Patients who recover from ES often continue with their post-transplant recovery as planned. Many report feeling back to their “pre-syndrome” health within 1 to 2 weeks, assuming there are no secondary complications.

Follow-up in some rare cases, where damage to the organs was noted, may include pulmonary rehab or nephrology consults. The majority of patients recover their immune system and lead a normal life, although they are monitored regularly in the first year after the transplantation.

Prevention & Risk Reduction Strategies

Can Engraftment Syndrome Be Prevented?

Although there are no sure measures to avoid engraftment syndrome, physicians can minimize the risk by monitoring it carefully and acting in time.17Hahn T, et al. (2008). Prevention strategies for engraftment syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma, 49(9), 1705–1713.

Preventive strategies may include:

- Close clinical observation during the engraftment window (days 7–14)

- Prophylactic corticosteroids in high-risk individuals

- Limiting fluid overload during transplant conditioning and early recovery

- Early empirical treatment of unexplained fevers or rashes with steroids in the absence of other causative factors.

Presently, certain transplant centers have established protocols to begin low-dose steroids on a prophylaxis basis for high-risk patients.

There is no guarantee of prevention, but at the same time, detecting the transplant complications at the early stage is the most potent tool against ES. Mostly, healthcare teams detect the syndrome before it can enter a perilous phase.

Role of the Healthcare Team in Risk Management:

Your medical team is not merely dosing medicines; they are your first line of defense against such complications as engraftment syndrome. Every participant in the transplant care team plays a very important role:18Flowers ME, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA. (2011). Multidisciplinary care in stem cell transplantation. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 8(7), 433–440.

- Transplant doctors observe lab values and clinical symptoms in neutrophil recovery

- First symptoms, which are usually fever or rash, are often the first to be noticed by nurses.

- Pharmacists adjust doses of drugs and deal with immunosuppressants

- ICU and pulmonary teams start immediately to manage when respiratory symptoms arise

It is an interdisciplinary approach that makes early diagnosis and treatment so efficient.

Conclusion

Engraftment syndrome is a complicated yet treatable problem of stem cell transplantation. Its symptoms could resemble those of other conditions, such as GVHD or infection, but early identification and treatment with corticosteroids can result in recovery. It is the clearest case of “better safe than sorry” in the health sector-diagnosis that is effective to combat a condition before it becomes a health emergency.

Knowledge on how and why engraftment syndrome arises, the distinctions between this and other conditions, and the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures can empower clinicians and patients both. Engraftment syndrome can be overcome with careful watch, active treatment, and education.

Refrences

- 1Spitzer TR. (2001). Engraftment syndrome: double-edged sword of hematopoietic cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 27(1), 1–2.

- 2Carreras E, Díaz-Ricart M. (2011). The role of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of HSCT-associated syndromes. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 46(2), 149-156.

- 3Maiolino A, Biasoli I, Lima J, Portugal R, Pulcheri W. (2003). Engraftment syndrome following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Haematol, 110(4), 190–195.

- 4Takanashi M, Arai S, Nakamura Y, Kanda Y. (2003). Symptoms and risk factors of engraftment syndrome in autologous and allogeneic transplantation. Int J Hematol, 78(4), 386–392.

- 5Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, Kim S, Seol M, Lee YS. (2005). Engraftment syndrome after stem cell transplantation: Clinical manifestations and risk factors. Leuk Res, 29(3), 277–282.

- 6Chaudhry MS, et al. (2016). Engraftment syndrome: A unique post-transplant complication. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther, 9(2), 66–71.

- 7Spitzer TR. (2001). Engraftment syndrome: an increasingly recognized transplant complication. Bone Marrow Transplant, 27(9), 893–898.

- 8Jacobsohn DA, Vogelsang GB. (2007). Acute graft-versus-host disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2, 35.

- 9Schuster MG, Cleveland J, Gill VJ. (2004). Diagnostic use of imaging in transplant complications. Curr Opin Oncol, 16(2), 121–125.

- 10Carreras E, et al. (2011). Distinguishing engraftment syndrome from GVHD: importance of early diagnostic markers. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 46(4), 469–475.

- 11Atkins HL, et al. (2003). Engraftment syndrome: diagnostic dilemmas in early post-transplant care. J Clin Oncol, 21(6), 1115–1120.

- 12Saliba RM, et al. (2002). Corticosteroids for the treatment of engraftment syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant, 30(6), 425–429.

- 13Pérez-Simón JA, et al. (2005). Supportive therapy in engraftment syndrome: current practice. Haematologica, 90(12), 1600–1604.

- 14Bajwa RPS, et al. (2016). Management of Engraftment Syndrome: Experience from a Tertiary Care Center. Transplant Proc, 48(10), 3550–3554.

- 15Fuji S, et al. (2012). Clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis after engraftment syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 18(12), 1818–1825.

- 16Armand P, et al. (2007). Prognostic implications of engraftment syndrome in stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant, 40(5), 433–439.

- 17Hahn T, et al. (2008). Prevention strategies for engraftment syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma, 49(9), 1705–1713.

- 18Flowers ME, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA. (2011). Multidisciplinary care in stem cell transplantation. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 8(7), 433–440.