What is Bullous Pemphigoid?

Bullous Pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune bullous disorder. It is a rare skin condition in which large fluid-filled blisters are formed. It usually occurs on skin areas prone to flexion, like the armpits, upper thigh, and abdomen. Moreover, it is most seen in older patients in their 8th decade.1Nousari, Hossein C., and Grant J. Anhalt. “Pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid.” The Lancet 354.9179 (1999): 667-672

Epidemiology of Bullous pemphigoid

As mentioned earlier, this disease is mostly seen in the elderly. However, rare case reports show its prevalence in children and adolescents.2Schwieger-Briel, Agnes, et al. “Bullous pemphigoid in infants: characteristics, diagnosis and treatment.” Orphanet journal of rare diseases 9 (2014): 1-12. This affects women more than men under 75 years, but after that, it affects men more, so there is no gender predilection.

The incidence of Bullous pemphigoid has increased in the past decade as a result of multiple comorbidities, an increase in life expectancy of an aging population, an escalation in the use of drugs that may trigger this disease, and better laboratory techniques and clinical diagnosis that differentiate the non-bullous and bullous presentations with accuracy.

Epidemiological studies demonstrate that it is more commonly seen in Europeans than in the Asian population.3Alpsoy, Erkan, Ayse Akman-Karakas, and Soner Uzun. “Geographic variations in the epidemiology of two autoimmune bullous diseases: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid.” Archives of Dermatological Research 307 (2015): 291-298.

Signs and Symptoms of Bullous Pemphigoid

Following are some of the symptoms that a healthcare provider can observe in a patient suffering from BP. However, symptoms may vary from individual to individual. Here is an elaboration of its distinct features.

- Non-bullous phase: The patient may experience nonspecific rash and itching weeks or months before blisters form, which may remain the only sign of the disease.

- The hallmark of Bullous Pemphigoid is large fluid-filled blisters or bullae greater than 1cm in diameter that eventually form crusted erosion. Nevertheless, despite their large size, these bullae are not very fragile.

- There are also eczematous lesions or hive-like, red, and pruritic rash.

- Notably, these blisters manifest along the folds and creases of the skin like the lower abdomen, arms, legs, groin, mouth, and armpits.

- The skin around the blisters may display variation in appearance, appearing normal or darker than normal, like red, purple, or shades of brown.

- Smaller blisters in the mouth and other suspectable mucous membranes may manifest in 10 to 25% of cases.4Schiavo, Ada Lo, et al. “Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies.” Clinics in Dermatology 31.4 (2013): 391-399.

Bullous pemphigoid lesions are seen on a patient’s leg.

Causes of Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune disease caused by a malfunction of the human immune system. Typically, the body produces antibodies to combat dangerous bacteria, viruses, and other potentially harmful foreign organisms. However, for unknown reasons, the body sometimes develops antibodies targeting a particular tissue.

Contributing Factors:

Although the reason for the development of BP is not clear yet, some contributing factors are linked to the occurrence of this disease.

Medication

Prescription of some medicines, such as etanercept (Enbrel), sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), furosemide (Lasix), and penicillin, may lead to the onset of the disease.

Old age

Mostly, Bullous Pemphigoid manifests in the 8th decade of life. However, healthcare providers observe some rare infantile and adolescent cases.

Light and radiation

Besides, medication ultraviolet light therapy for treating skin diseases and radiotherapy for treating cancers can trigger Bullous Pemphigoid.

Medical Conditions

Lastly, some medical disorders like psoriasis, lichen planus, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and multiple sclerosis can also trigger Bullous Pemphigoid.

Pathophysiology of Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder. Its pathophysiology involves an immune-mediated process in which the normal adhesion between the epidermis (the outer layer of the skin) and the underlying dermis is disrupted.

Auto-immune Response :

In this condition, an integral part of the skin structure is disrupted. IgG autoantibodies are formed that target the basement membrane zone of the skin. The immune system mistakenly recognizes and targets proteins Bullous Pemphigoid Antigen 180 (BP180, Collagen XVII) and Bullous Pemphigoid antigen 230 (BP230), both are essential for adhesion between the epidermis and dermis.5Di Zenzo, G., Marazza, G., & Borradori, L. (2006). Bullous Pemphigoid: Physiopathology, Clinical Features and Management. Advances in Dermatology, 23, 257-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yadr.2007.07.013

Inflammatory Cellular Immune Response:

Next, autoantibodies attached to the structural proteins BP180 and BP230 start an inflammatory response, which triggers the recruitment of eosinophils and neutrophils to the affected area. The inflammation causes space between the epidermis and dermis, forming a fluid-filled blister.

Complement Activation:

After that, the complement system, which is part of the immune system, activates. It enhances the inflammatory response, releasing inflammatory mediators that further damage the tissue, exacerbating the immune response and blister formation.

Bullae Stage of Bullous Pemphigoid:

Finally, the activation of an auto-immune response, inflammatory cell infiltration, secretion of proteases, and activation of the complement system interfere with the adhesion of the basement membrane, leading to bullae formation.

Understanding the pathophysiology of Bullous Pemphigoid is crucial for developing a treatment plan for the disease.

How Is Bullous Pemphigoid Diagnosed?

There are no well-established criteria for diagnosis of Bullous Pemphigoid. However, combining clinical findings and laboratory tests can help confirm the disease.

Clinical Findings:

Firstly, healthcare providers will perform a detailed physical examination and medical history. They will look for key clinical findings, such as large fluid-filled bullae, blisters, itching, and the distribution of the lesions.

Secondly, they must differentiate the lesions from other skin diseases that present similarly, such as pemphigus vulgaris, dermatitis herpetiformis, and epidermolysis bullosa. All these have different treatment plans and courses of action, so correct diagnosis is crucial.

Laboratory Tests:

Laboratory investigations are crucial in confirming the diagnosis and understanding the underlying immunopathogenesis. A comprehensive physical examination is essential before ordering tests.

Conduct a Complete Blood Count

This can provide important insights into the patient’s overall well-being. Furthermore, this diagnostic workup can also diagnose any underlying medical conditions and complications. Even though this test is not specific to BP, it can show a high eosinophil count, indicating a high inflammatory or allergic response.

Undertake the Serological test (ELISA)

ELISA is an Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay that detects autoantibodies targeting proteins in the basement membrane zone of the skin, such as BP180 (Collagen XVII) and BP230. The presence of these two autoantibodies confirms the diagnosis.

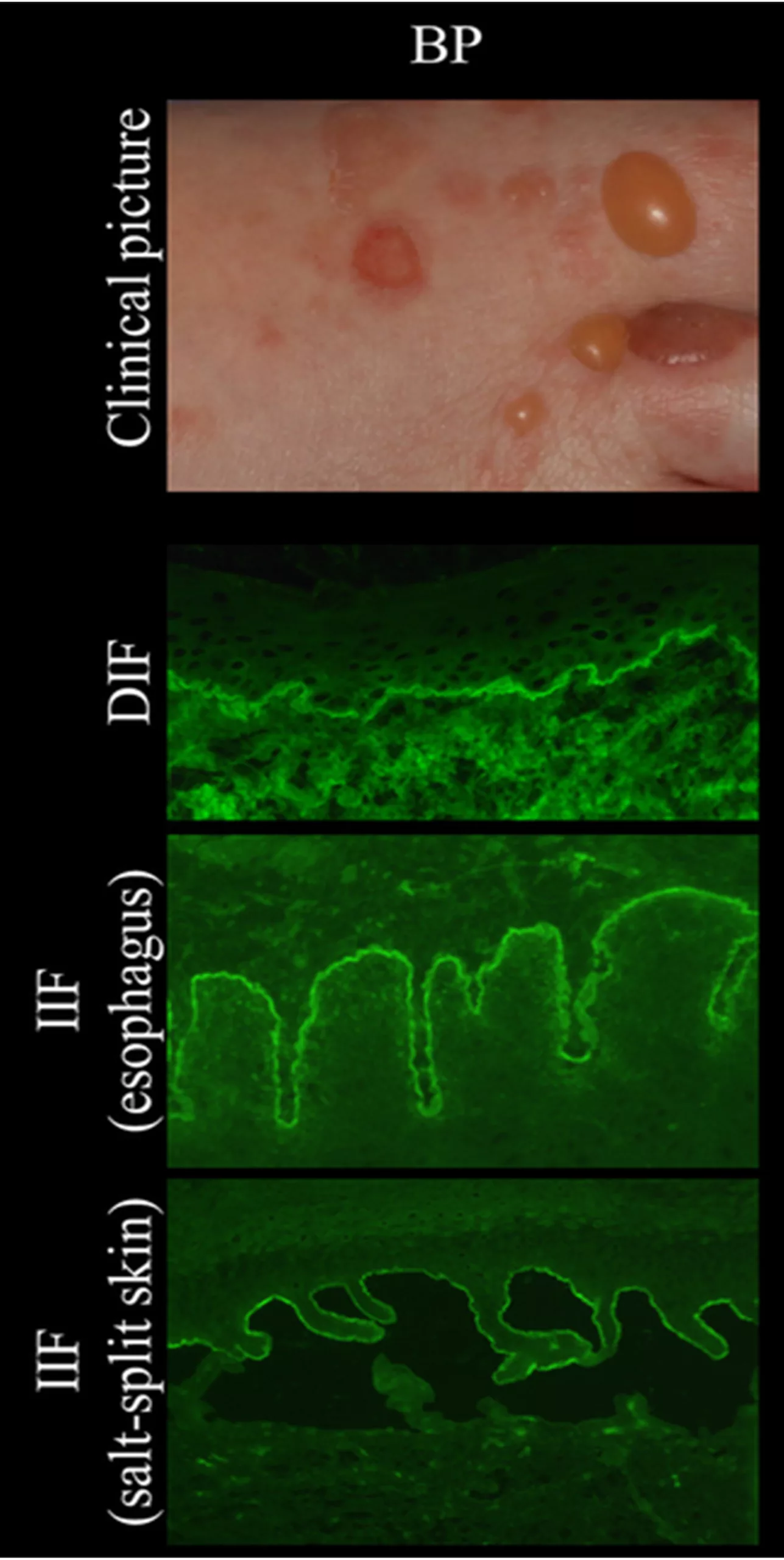

Direct Immunofluorescence (DIF)

Linear deposition of IgG antibodies along the skin’s basement membrane in the skin biopsy sample confirms autoimmune disease.

Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF)

Serum testing may reveal the presence of autoantibodies against BP180 (Collagen XVII) and BP230 antigens, confirming the diagnosis.

Serum levels of Inflammatory markers

Analyze C-reactive protein (CRP) and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) to determine the underlying inflammatory process. The rise in CRP levels indicates inflammation in the body, which is seen in active BP. Similarly, the increase in the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate also suggests an underlying inflammatory response.

Perform skin biopsy

During this procedure, a small section of the blister, the edge of the blister, and normal skin are surgically removed and examined under a microscope.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Analyzing the biopsy specimen typically reveals the characteristics of BP, including subepidermal blistering, eosinophilic infiltration within the blister cavity and the underlying dermis, and linear deposition of immunoglobulins and complement components along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy.

Other investigations

Carry out chest X-rays and or abdominal ultrasounds to assess the potential complications caused by BP. Patients with BP may develop pneumonia or gastrointestinal problems.

The patient’s history, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and histopathological examination confirm the diagnosis of Bullous Pemphigoid.

Treatment

The main focus of treatment in Bullous Pemphigoid is relieving the symptoms of the disease, reducing inflammation, controlling autoimmune response, and minimizing the side effects of the medicines. Doctors may give a combination of medicines depending on the severity of the disease. The treatment will be as follows.

Administering Topical Corticosteroids

For mild cases, topical corticosteroids are given. These high-potency corticosteroids are applied directly to the lesion, reducing inflammation and blister formation.

Systemic corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids, like prednisolone, are given, but continuously long use can have side effects like diabetes, weak bones, high blood pressure, and a risk of infections. These are usually used when corticosteroids alone are not enough or not well tolerated. Gradual tapering is necessary to minimize side effects.

Immunosuppressive drugs

These drugs inhibit the production of the body’s white blood cells, suppressing immunity. Examples include azathioprine, mycophenolate, mofetil, and methotrexate.

Rituximab

If signs and symptoms involve the eyes and upper digestive tract, Rituximab is given. This monoclonal antibody therapy targets B cells involved in the autoimmune response.

Combination of antibiotics

Some evidence suggests that Tetracycline and Nicotinamide may effectively reduce inflammation and autoantibody production.

Symptomatic treatment

Prescription of pain relief medicines and anti-histamines can reduce itching and discomfort.

Wound Care

Proper wound care, including gentle cleansing and non-adherent dressings, is essential to prevent infection and promote healing of blisters and erosions.

Is this condition Contagious?

Contagiousness of Bullous Pemphigoid is a great concern for the patient and the caregivers. It is not contagious as it is caused by an autoimmune disorder characterized by the production of autoantibodies against the skin’s basement membrane. BP may seem like an infectious skin disease due to blisters, but it does not spread by direct contact or airborne transmission. The autoimmune mechanism of BP differentiates it from other infectious diseases.6Kasperkiewicz, Michael, Detlef Zillikens, and Enno Schmidt. “Pemphigoid diseases: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.” Autoimmunity 45.1 (2012): 55-70.

Life Expectancy and Mortality

Bullous Pemphigoid (BP) can vary greatly in severity, and individual cases may have different outcomes. Generally, timely diagnosis and proper treatment can lead to a favorable prognosis. However, in severe cases with more areas affected by the disease, the prognosis can be poor and can lead to early death.7Langan, S. M., et al. “Mortality of Bullous Pemphigoid in the UK: A Population-Based Cohort Study.” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 167, no. 4, 2012, pp. 818-824. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11045.x.

Bullous pemphigoid vs Pemphigus Vulgaris

The immune system normally fights infections, but in pemphigus and pemphigoid, the immune system forms antibodies against normal body structures in the skin, causing blisters.

The diagnosis of skin diseases needs to be accurate so that appropriate treatment can be given. There is a difference between pemphigus and pemphigoid.8Kayani, Mahaz, and Arif M. Aslam. “Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris.” bmj 357 (2017).

Pemphigus is characterized by shallow ulcers or fragile blisters that break open quickly.

Pemphigoid presents with stronger or “tense” blisters that don’t open easily. Those with pemphigoid are also more likely to have hot, red, and itchy hive spots.

| Pemphigus Vulgaris | Bullous pemphigoid | |

| Age | Usually 40 – 60 years. | Above 70 years. |

| Time Course | Chronic, relapse | Chronic, relapse |

| Symptoms | Painful | Itchy |

| Mucosal Involvement | Often seen | Only in 10-30% of cases |

| Blisters | These form within the epidermal layers and are often in the lowest section | These form beneath the epidermis |

| Bullae | Fragile, flaccid, and already ruptured. | Bullae tense |

| Antibodies | Autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 and 3. | Hemidesmosome antigens BP180 (Collage XVII) and BP230 |

| Nikolsky sign* | Positive | Negative |

| Histology | Tombstone appearance of the basal layer | Eosinophil infiltration |

| Direct Immunofluorescence | Net-like IgG | Linear IgG |

| Prognosis | Poor | Good |

*Nikolsky sign: This is a skin finding in which the top layer of skin slips away from the lower layers when rubbed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Bullous Pemphigoid is an autoimmune disorder characterized by large fluid-filled blisters on the skin. The exact cause of the disease is unknown. Diagnosis relies on clinical evaluation, lab tests, and histopathology. Despite the chronic nature of the disease, good treatment options are available, which improve the patient’s life. Still, some severe cases can be difficult to manage. Ongoing research aims to enhance understanding and refine therapies for better patient outcomes.

Refrences

- 1Nousari, Hossein C., and Grant J. Anhalt. “Pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid.” The Lancet 354.9179 (1999): 667-672

- 2Schwieger-Briel, Agnes, et al. “Bullous pemphigoid in infants: characteristics, diagnosis and treatment.” Orphanet journal of rare diseases 9 (2014): 1-12.

- 3Alpsoy, Erkan, Ayse Akman-Karakas, and Soner Uzun. “Geographic variations in the epidemiology of two autoimmune bullous diseases: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid.” Archives of Dermatological Research 307 (2015): 291-298.

- 4Schiavo, Ada Lo, et al. “Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies.” Clinics in Dermatology 31.4 (2013): 391-399.

- 5Di Zenzo, G., Marazza, G., & Borradori, L. (2006). Bullous Pemphigoid: Physiopathology, Clinical Features and Management. Advances in Dermatology, 23, 257-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yadr.2007.07.013

- 6Kasperkiewicz, Michael, Detlef Zillikens, and Enno Schmidt. “Pemphigoid diseases: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.” Autoimmunity 45.1 (2012): 55-70.

- 7Langan, S. M., et al. “Mortality of Bullous Pemphigoid in the UK: A Population-Based Cohort Study.” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 167, no. 4, 2012, pp. 818-824. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11045.x.

- 8Kayani, Mahaz, and Arif M. Aslam. “Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris.” bmj 357 (2017).