What is Fat Embolism Syndrome?

Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a condition in which fat particles get into your bloodstream and block blood flow. The blockage can affect various body parts, including the lungs, brain, skin, and others. Fat embolism syndrome is a clinical phenomenon characterized by the systemic dissemination of fat emboli within the systemic circulation. The dissipation of fat emboli disrupts the capillary bed and affects microcirculation, causing a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Fat embolism refers to the presence of fat particles in the microcirculation, while FES is the systemic manifestation of these fat emboli, resulting in widespread symptoms.1Luff, D., & Hewson, D. W. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome. BJA education, 21(9), 322-328.

Fat emboli are most commonly associated with fractures of long bones in the lower part of the body, including the tibia (shinbone), pelvis, and femur (thighbone). Fat emboli are generally resolved independently but sometimes can result in FES. FES is a rare condition that is typically not considered severe. However, in its severity, it is linked with neurocognitive deficit, respiratory failure, and even death.

FES can be seen in 3 to 4% of individuals with fractures in one long bone. The percentage is higher, up to 15%, in those with many long bone fractures. It is a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. However, prompt recognition is important so that the best possible therapy can be started immediately.2Weinhouse, G. L., & Parsons, P. F. G. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome. http..//www. uptodate, com, 2012-10-15/2013-05-20.

Causes & Risk Factors of FES

FES can affect anyone, although it is relatively uncommon in children. It is most likely to occur when a person experiences a significant injury to their pelvis or any other long bone. In about 95% of the cases, the leading cause is a fracture of the long bones. Fat particles enter the bloodstream and often lodge in small blood vessels, known as capillaries, near the skin’s surface. This can result in a rash and other mild symptoms.3Kosova, E., Bergmark, B., & Piazza, G. (2015). Fat embolism syndrome. Circulation, 131(3), 317-320.

Traumatic Causes:

- Massive soft tissue damage

- Crush injury

- Prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Severe burn involving more than 50% of body surface area

- Bone marrow transplantation

- Liposuction

- Median sternotomy

Non-Traumatic Causes:

Cases of nontraumatic FES are rare and include the following:

- Fatty Liver

- Acute or chronic pancreatitis

- Therapy with corticosteroid

- Infusion of fat emulsion

- Lymphography

- Hemoglobinopathies

- Sickle cell disease

- Thalassemia

Several risk factors are associated with the development of FES. The following conditions increase the risk of developing FES:

- Being male

- Having a closed fracture

- Having multiple fractures

- Between the ages of 20 and 304Alpert, M., Grigorian, A., Scolaro, J., Learned, J., Dolich, M., Kuza, C. M., … & Nahmias, J. (2020). Fat embolism syndrome in blunt trauma patients with extremity fractures. Journal of Orthopaedics, 21, 475-480.

Pathophysiology of the FES

The particles of fat enter the circulatory system and damage the capillary beds. The embolized fat within these capillaries leads to tissue damage and triggers a systemic inflammatory response. The pulmonary system is most commonly affected by the damage, but fat emboli can also lodge in the microcirculatory systems of the skin, heart, eyes, and brain.5Timon, C., Keady, C., & Murphy, C. G. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome–a qualitative review of its incidence, presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal, 15(1), 1.

Generally, two theories for FE formation are known. These are biochemical and mechanical theories.

Mechanical Theory:

After a traumatic injury, fat particles are directly released into the circulation from the bone marrow. Fat globules are released due to elevated pressure in the medullary cavity, which causes the release of fat globules into the venous system. The medullary cavity is the central cavity of the bone where the bone marrow is stored. Veins carry the blood to the right heart. From the heart, the blood is then propelled to the lungs for reoxygenation. Fat globules may become lodged in the pulmonary circulation, obstructing the small vessels.

They may also pass from the lung circulation and back into the left ventricle. From here, it can also be pumped through the body through systemic circulation. If a significant portion of the capillary network in the lungs (around 80%) becomes obstructed by fat globules, the resulting back pressure on the right side of the heart increases its workload, potentially leading to acute right heart failure.6Bajraktari, M., Naco, M., Huti, G., Arapi, B., & Domi, R. (2022). Fat Embolism Syndrome Without Bone Fracture: Is It Possible? Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 10(C), 331-335..

Biochemical Theory:

After a long bone injury, inflammation causes the bone marrow to release fatty acids into the venous circulation. These fatty acids, along with the inflammatory response, cause damage to the capillary beds in organs, particularly the lungs. This theory also explains the non-traumatic origins of Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES).7Ali, Z., kTroncoso, J. C., & Redding‐Ochoa, J. (2024). Fat embolism syndrome associated with atraumatic compartment syndrome of the bilateral upper extremities: An unreported etiology. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 69(2), 718-724.

Symptoms of FES

FES usually develops within two to three days after a traumatic injury in any of the major bones. It can also occur as soon as 12 hours after that injury, and the main symptoms of FES include:

Changes in Mental State

FES can affect the functioning of your brain. It can cause confusion, headaches, unresponsiveness, slow response, and personality changes. It can also involve seizures and eventually a state of coma.

Respiratory Distress or Trouble in Breathing

Fast breathing (Tachypnea) or struggling to breathe (Dyspnea) is a common symptom of FES. These symptoms develop earlier than all other symptoms. In severe cases, respiratory failure can also occur.

Petechial Rash

Petechiae are small bruise-like rash-like spots on the skin. These rashes occur when blood vessels like capillaries break or burst. Such spots generally appear on your arms, chest, neck, and head. These can also occur on the inner sides of your mouth and the inner side of your eyelids.8Kwon, J., & Coimbra, R. (2023). Fat embolism syndrome after trauma: What you need to know. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 10-1097.

Some other common symptoms include:

- Fever

- Increased heart rate (Tachycardia)

- Jaundice (It is a liver disorder that causes the yellowing of the whites of your eyes and your skin)

- Changes in vision

Clinicians also test for some clinical signs, and these signs include:

- Low oxygen saturation in blood

- Renal problems

- Fat in urine (Faturia)

- Anemia

- Low platelet count and some other variations in the blood chemistry.

Diagnosis of FES

The doctor makes a diagnosis based on your symptoms and physical examination. The physical examination involves examining the body and symptoms of potential medical complications. The clinical identification of shortness of breath, petechial rash, and cognitive impairment within the first few days following trauma, long-bone fractures, or intramedullary surgery is key to recognizing Fat Embolism Syndrome.

Laboratory Tests:

A complete blood count and lipid profile blood tests are usually performed. These tests look for some critical changes in the blood chemistry. CBC typically shows anemia and thrombocytopenia. Arterial blood gas (ABG) may show low oxygen levels (hypoxemia). Ventilation-perfusion mismatch is a hallmark of FES. These tests will also detect traces of fat particles in the urine, sputum, or blood. Sputum is the mucus you cough out.

Diagnostic Tests:

These tests are required when symptoms of FES affect your heart. These tests include an electrocardiogram (ECG). It measures the electrical activity of the heart. Additionally, a skin biopsy will identify signs of fat particles blocking the skin’s capillaries.9Glazer, J. L., & Onion, D. K. (2001). Fat embolism syndrome in a surgical patient. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 14(4), 310-313.

Imaging Studies:

Physicians can first take X-rays. The chest X-ray typically shows diffuse interstitial markings, pulmonary edema, lung infiltrates, and a “snowstorm” appearance with flake-like pulmonary markings.

After that, a computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of your chest or head will be done. These studies are performed to identify life-threatening problems like pulmonary embolism and stroke. These scans help find these conditions and confirm a diagnosis.

CT scan

The typical manifestations of FES on CT scan are septal thickening and nodular opacities. These suggest fat emboli obstructing the pulmonary vasculature.

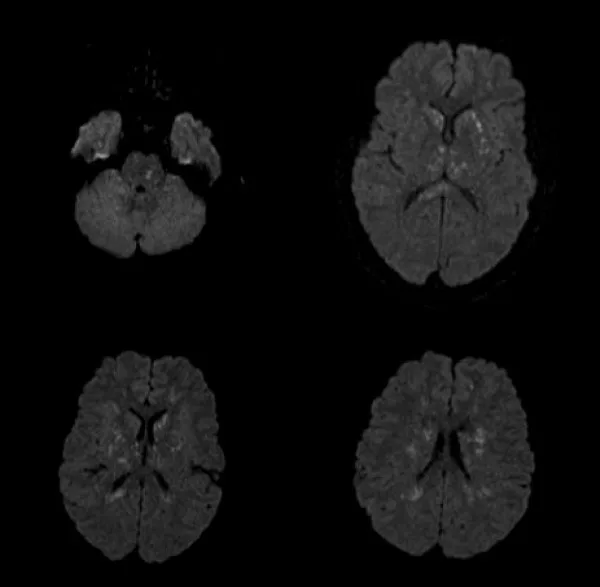

MRI

In cerebral fat embolism, MRI shows multiple, scattered, small, nonconfluent, and hyperintense lesions on T2 weighted scans. These findings are often referred to as the “starfield pattern” and are associated with fat emboli affecting the brain’s microcirculation.10Aravapalli A, Fox J, Lazaridis C. Cerebral fat embolism and the “starfield” pattern: a case report. Cases J. 2009 Nov 19;2:212. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-212. PMID: 19946456; PMCID: PMC2783161.

Criteria for Diagnosing FES:

Three diagnostic criteria can be used for FES. Guard and Wilson’s Criteria (table 1), Lindeque’s criteria, and Schonfeld’s scoring criteria (table 2). Guard and Wilson’s criteria are one of the commonly used criteria for diagnosing FES.11Gurd, A. R. (1970). Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume, 52(4), 732-737.

| Table 1: Guard and Wilson’s Criteria | |

| Major Guard and Wilson’s criteria | Minor Guard and Wilson criteria |

| Cerebral indications in non-head injury cases | Jaundice |

| Respiratory distress | Drop in hemoglobin |

| Petechial Rash | Renal changes |

| Retinal changes | |

| Fever ( > 38.5 o C) | |

| Tachycardia ( > 110 bpm) | |

| Elevated sedimentation rate of erythrocyte | |

| New-onset thrombocytopenia | |

| Fat macroglobulinemia | |

| One or two major and four minor points propose a diagnosis of FES. | |

| Table 2: Lindeque’s Criteria and Schonfeld’s Scoring System | |

| Lindeque’s Criteria | Schonfeld’s Scoring System |

| pO2 < 8 kPa (partial pressure of oxygen) | Petechial rash (five points) |

| pCO2 > 7.3 kPa (partial pressure of carbon dioxide) | Diffused infiltrates on the chest (four points) |

| Respiratory rate > 35 per minute, despite sedation | Hypoxemia (three points) |

| Anxiety, tachycardia, dyspnea 12Lindeque, B. G., Schoeman, H. S., Dommisse, G. F., Boeyens, M. C., & Vlok, A. L. (1987). Fat embolism and the fat embolism syndrome. A double-blind therapeutic study. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume, 69(1), 128-131. | Tachycardia (one point) |

| Fever (one point) | |

| Tachypnea (one point) | |

| Confusion (one point) | |

| Lindegue suggested using respiratory symptoms alone as the diagnostic criteria for FES. This criterion is not widely accepted. | A score greater than five will suggest FES 13Schonfeld, S. A., Ploysongsang, Y., DiLISIO, R. A. L. P. H., Crissman, J. D., Miller, E., Hammerschmidt, D. E., & JACOB, H. S. (1983). Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids: a prospective study in high-risk patients. Annals of Internal Medicine, 99(4), 438-443. |

Treatment of FES

Generally, there is no cure or standard treatment plan for this condition. Treatment of FES includes some medications, operative options, and supporting devices to prevent further complications.

The main goal of the treatment options is to provide some supportive care. It means treatment options focus on managing symptoms and underlying effects rather than the disease.

Pharmacological Intervention:

Possible medications used for FES include:

Corticosteriod Therapy

Corticosteroids decrease inflammation in the body. Methylprednisolone is the most prescribed steroid. Physicians often recommend them to lessen inflammation in the lungs, which might make breathing easier. However, it is not a standard treatment option.

Supportive Treatments:

Supportive treatments focus on managing the symptoms of the condition. Some supportive treatments can help alleviate or reduce the risk of FES.

Oxygen

Increasing the oxygen supply to the patients means the lungs and heart do not have to work hard. It can prevent the effects of FES. Oxygen supply is one of the easiest and fastest treatments for respiratory problems.

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

It is a process that pulls the blood out of the body. This process requires a particular sequence of devices. These devices add oxygen and remove carbon dioxide. After that, the blood travels backward into your body. ECMO allows the lungs to rest and heal, which is especially beneficial for patients experiencing severe respiratory failure, such as from Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES).14Momii K, Shono Y, Osaki K, Nakanishi Y, Iyonaga T, Nishihara M, Akahoshi T, Nakashima Y. Use of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for perioperative management of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by fat embolism syndrome: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Feb 26;100(8):e24929. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024929. PMID: 33663129; PMCID: PMC7909122.

Ventilation

The ventilator performs the function of breathing, so you do not have to. It is the most common part of management, particularly for people who suffer from life-threatening breathing difficulties. The process begins with intubation, which involves inserting a tube down your windpipe and attaching it to the ventilator. The patients are usually sedated during the process to help keep them comfortable.

Complications of FES

FES typically does not have any direct complications. The most severe cases can result in long-term side effects on your lungs, brain, and eyes. Some evidence suggests that FES can put you at a higher risk for complications like deep vein thrombosis. The most complications include:

- Pulmonary edema

- Cardiac arrest

- Septic shocks

- Long-term neurological damage

- Chronic lung diseases

- Renal dysfunction

- Respiratory distress

Complications can vary among individuals. You can consult your clinician about the possible side effects specific to your case. Healthcare providers are an excellent source of information. The healthcare providers can tailor that information according to your circumstances and case details. Once you have completely recovered from FES, there are no more long-term complications.

Prevention

Doing your best to avoid broken bones is the best step in preventing FES. In case of any traumatic injury, surgical fixation will help in preventing FES from occurring.

Surgical Fixation:

Early surgical fixation of long bone fractures can decrease the incidence of FES. The use of internal fixation devices can also reduce the incidence. Surgical techniques used to reduce embolisms include:

- Making a hole in the cortex (reduces intramedullary pressure).

- Venting of the femur

- Leveraging bone marrow before fixation (reduces marrow embolization)

- Use of tourniquets

- Use of a bone vacuum

Yet, there is not enough evidence to support a clear reduction of FES with these surgical techniques.15Kwiatt, M. E., & Seamon, M. J. (2013). Fat embolism syndrome. International journal of critical illness and injury science, 3(1), 64-68.

Prevention Tips:

Remove slipping hazards from your home, make sure your shoes fit properly, and practice balance-improving exercises such as yoga. But if bones do break and you need orthopedic surgery, keep these things in mind.

- If you have a broken long bone, limit your movement. The more immobile you are, the lower your chances of developing FES.

- If you need surgery to fix the broken bone, it should be performed earlier. Surgery that starts within 24 hours of the bone breakage carries less risk of FES.

- The use of prophylactic steroids is effective in preventing FES in orthopedic surgery.

Fat Embolism Syndrome Vs. Pulmonary Embolism

You can spot the difference between an FES and a pulmonary embolism in their definitions.

An embolism is a blockage in the blood vessels caused by one or more fat particles. This occurs due to air bubbles, blood lumps, and when fat particles circulate in the bloodstream.

Fat embolism is an obstruction in the blood vessels due to the fat particles.

A pulmonary embolism is a blockage or obstruction in the lungs’ blood vessels. 16Konstantinides, S. V., Barco, S., Lankeit, M., & Meyer, G. (2016). Management of pulmonary embolism: an update. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 67(8), 976-990.

Blood clots are the main culprits of pulmonary embolism. But, FES can cause pulmonary embolisms, as well. These embolisms are more life-threatening and present health emergencies. FES is also a source of breathing problems even when it does not cause pulmonary embolisms. While both of these embolisms can cause breathing difficulties, FES has its own set of symptoms. A clear understanding of the differences between these two types of embolisms is crucial for an accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Vs. FES

ARDS is characterized as an acute, inflammatory, diffuse lung injury that poses a significant threat to seriously ill patients. Key features of ARDS include poor oxygenation, pulmonary infiltrates, and an acute onset. In contrast, FES is primarily a clinical problem, while ARDS can be considered a severe complication of FES. The exact pathogenesis of ARDS in the context of FES remains unclear.17Diamond, M., Peniston, H. L., Sanghavi, D. K., & Mahapatra, S. (2024). Acute respiratory distress syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

Conclusion

FES is a rare condition. FES most commonly presents with respiratory distress in patients with orthopedic trauma. There is no specific diagnostic test or criteria for this condition. Different therapies are directed at treating the symptoms of this condition. Early surgical fixation of the bone fractures can reduce the occurrence of FES. Shortness of breath or neurological deficits can occur. Pneumonia and heart failure can also present similar symptoms to FES. However, in these two disorders, symptoms develop slowly. But they can confuse the emergency staff. If you suspect FES in yourself, immediate medical attention is required. Seek emergency care in case of the appearance of severe symptoms.

Refrences

- 1Luff, D., & Hewson, D. W. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome. BJA education, 21(9), 322-328.

- 2Weinhouse, G. L., & Parsons, P. F. G. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome. http..//www. uptodate, com, 2012-10-15/2013-05-20.

- 3Kosova, E., Bergmark, B., & Piazza, G. (2015). Fat embolism syndrome. Circulation, 131(3), 317-320.

- 4Alpert, M., Grigorian, A., Scolaro, J., Learned, J., Dolich, M., Kuza, C. M., … & Nahmias, J. (2020). Fat embolism syndrome in blunt trauma patients with extremity fractures. Journal of Orthopaedics, 21, 475-480.

- 5Timon, C., Keady, C., & Murphy, C. G. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome–a qualitative review of its incidence, presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal, 15(1), 1.

- 6Bajraktari, M., Naco, M., Huti, G., Arapi, B., & Domi, R. (2022). Fat Embolism Syndrome Without Bone Fracture: Is It Possible? Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 10(C), 331-335.

- 7Ali, Z., kTroncoso, J. C., & Redding‐Ochoa, J. (2024). Fat embolism syndrome associated with atraumatic compartment syndrome of the bilateral upper extremities: An unreported etiology. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 69(2), 718-724.

- 8Kwon, J., & Coimbra, R. (2023). Fat embolism syndrome after trauma: What you need to know. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 10-1097.

- 9Glazer, J. L., & Onion, D. K. (2001). Fat embolism syndrome in a surgical patient. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 14(4), 310-313.

- 10Aravapalli A, Fox J, Lazaridis C. Cerebral fat embolism and the “starfield” pattern: a case report. Cases J. 2009 Nov 19;2:212. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-212. PMID: 19946456; PMCID: PMC2783161.

- 11Gurd, A. R. (1970). Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume, 52(4), 732-737.

- 12Lindeque, B. G., Schoeman, H. S., Dommisse, G. F., Boeyens, M. C., & Vlok, A. L. (1987). Fat embolism and the fat embolism syndrome. A double-blind therapeutic study. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume, 69(1), 128-131.

- 13Schonfeld, S. A., Ploysongsang, Y., DiLISIO, R. A. L. P. H., Crissman, J. D., Miller, E., Hammerschmidt, D. E., & JACOB, H. S. (1983). Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids: a prospective study in high-risk patients. Annals of Internal Medicine, 99(4), 438-443.

- 14Momii K, Shono Y, Osaki K, Nakanishi Y, Iyonaga T, Nishihara M, Akahoshi T, Nakashima Y. Use of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for perioperative management of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by fat embolism syndrome: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Feb 26;100(8):e24929. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024929. PMID: 33663129; PMCID: PMC7909122.

- 15Kwiatt, M. E., & Seamon, M. J. (2013). Fat embolism syndrome. International journal of critical illness and injury science, 3(1), 64-68.

- 16Konstantinides, S. V., Barco, S., Lankeit, M., & Meyer, G. (2016). Management of pulmonary embolism: an update. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 67(8), 976-990.

- 17Diamond, M., Peniston, H. L., Sanghavi, D. K., & Mahapatra, S. (2024). Acute respiratory distress syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.