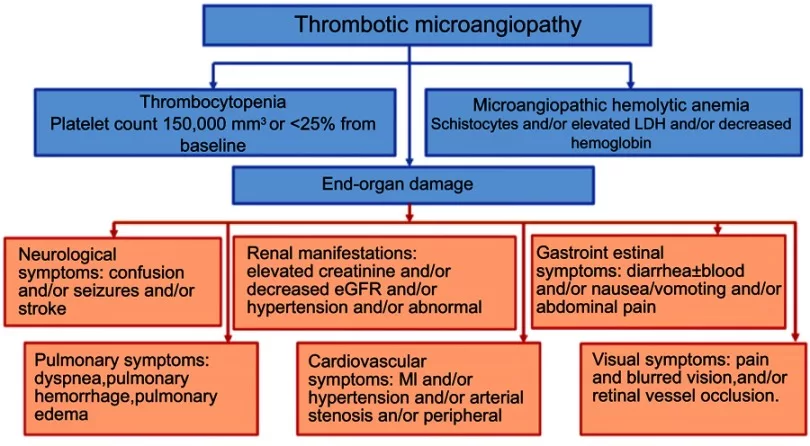

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a rare yet potentially serious disorder characterized by damage to the kidney’s blood vessels. It is a type of thrombotic microangiopathy in which lesions form in the small blood vessels. The disease is called a syndrome because it is a combination of:

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (breakdown of red blood cells due to narrowing of vessels)

- Acute kidney injury (especially in children)

The overall prevalence of HUS is estimated to be approximately 2-3 cases/100,000 people.1Aldharman, S. S., Almutairi, S. M., Alharbi, A. A., Alyousef, M. A., Alzankrany, K. H., Althagafi, M. K., … & Jamil, S. F. (2023). The prevalence and incidence of hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review. Cureus, 15(5). It is a major cause of acute kidney injury in children. There are multiple causes of HUS but E. Coli infection is the most prevalent. The most common symptoms include confusion, abdominal pain/cramping, urinary abnormalities, diarrhea, hypertension, etc. Treatment involves symptomatic management, antibiotics, and blood transfusions. Despite the seriousness of the disease, most patients make a full recovery with optimum treatment.

Types Of Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

There are different types of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Diagnosing the exact type is crucial for the correct therapy.

Typical HUS

Also known as Shiga toxin-associated HUS, typical HUS is the most common type of HUS, comprising about 90% of the cases. The main cause of typical HUS is Shiga toxin produced by Escherichia coli bacteria (Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli). Most victims are children younger than 5 years.

In several cases, typical hemolytic uremic syndrome develops after bowel (intestine) infection. Therefore, a typical initial presentation of the condition is bloody diarrhea, which develops 2-3 days after bacterial exposure. Symptoms of HUS usually develop 3-10 days after onset of diarrhea.2Joseph, A., Cointe, A., Mariani Kurkdjian, P., Rafat, C., & Hertig, A. (2020). Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: A narrative review. Toxins, 12(2), 67.

In several cases, typical hemolytic uremic syndrome develops after bowel (intestine) infection. Therefore, a typical initial presentation of the condition is bloody diarrhea, which develops 2-3 days after bacterial exposure. Symptoms of HUS usually develop 3-10 days after onset of diarrhea.2Joseph, A., Cointe, A., Mariani Kurkdjian, P., Rafat, C., & Hertig, A. (2020). Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: A narrative review. Toxins, 12(2), 67.

Atypical HUS

The atypical type of hemolytic uremic syndrome is rare and only 5-10% of cases of HUS are atypical. You inherit the atypical type from your parents. This particular type is the result of genetic mutation in the alternative complement pathway.3Harboe, M., & Mollnes, T. E. (2008).The alternative complement pathway revisited. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 12(4), 1074-1084.

The complement system is your body’s front line of defense working for the immune system (complements the body’s army against infection). It activates specific proteins that defend your body against foreign pathogens and helps the body heal after infection/injury.

Genetic mutation in this efficient pathway causes devastating effects such as activation of the coagulation cascade and vessel damage. These steps manifest as thrombotic microangiopathy and thereby; hemolytic uremic syndrome. You can find the usual symptoms of low platelet count, low levels of RBCs, and acute kidney failure. Additionally, you can observe hypertension in such patients (that worsens quickly).

Secondary HUS

When hemolytic uremic syndrome co-exists with co-morbidities, the condition is called secondary HUS. It arises secondary to some underlying condition (mostly infection). Streptococcus pneumonia infection is the most prevalent cause of secondary HUS in children (5-15% of all cases).

Pregnancy-Associated Atypical HUS (p-aHUS)

A rare type of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome is pregnancy-associated HUS. The disease is characterized by typical symptoms of acute kidney injury, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. However, it is a life-threatening condition that requires quick diagnosis and prompt treatment. Diagnosing pregnancy-associated HUS is tricky as it mimics different diseases of pregnancy and postpartum.4Gupta, M., Govindappagari, S., & Burwick, R. M. (2020). Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 135(1), 46-58. Reports suggest that p-aHUS affects 1/25,000 pregnancies (mostly during the postpartum period).5Saad, A. F., Roman, J., Wyble, A., & Pacheco, L. D. (2016). Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. American Journal of Perinatology Reports, 6(01), e125-e128.

In a reported case of p-aHUS, symptoms appeared at 26.3 weeks of gestation with typical presentations of the hemolytic syndrome. In addition to this, the patient suffered from septic shock and neurological alterations. Therefore, doctors advise immediate diagnosis and treatment in all cases of pregnancy-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome.6Barrera‐Hoffmann, C., Mariaca‐Ortíz, Y., Ruiz‐Villa, J. G., Cuevas‐Cruz, L. E., López‐Mendoza, M. D. R., & Briones‐Garduño, J. C. (2024). Pregnancy‐associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Case report. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research.

In a reported case of p-aHUS, symptoms appeared at 26.3 weeks of gestation with typical presentations of the hemolytic syndrome. In addition to this, the patient suffered from septic shock and neurological alterations. Therefore, doctors advise immediate diagnosis and treatment in all cases of pregnancy-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome.6Barrera‐Hoffmann, C., Mariaca‐Ortíz, Y., Ruiz‐Villa, J. G., Cuevas‐Cruz, L. E., López‐Mendoza, M. D. R., & Briones‐Garduño, J. C. (2024). Pregnancy‐associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Case report. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research.

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Symptoms

There are multiple manifestations of the disease. Some symptoms are tolerable, while others can be life-threatening.

Diarrhea:

A significant number of patients report bloody diarrhea (loose stools with blood). Initially, diarrhea was considered a must symptom of E.coli infection and hemolytic uremic syndrome. However, later on, doctors found out that patients may suffer from HUS without showing signs of diarrhea. Therefore, the terms “diarrhea positive HUS” and “diarrhea negative HUS” came into use. Though the terminology is not in use anymore, it signifies the number of HUS cases suffering from diarrhea.7Viteri, B., & Saland, J. M. (2020). Hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatrics In Review, 41(4), 213-215. Usually, bloody diarrhea is seen 2-3 days after pathogen exposure.

Even today, medical practitioners use the term diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome to explain the thrombotic microangiopathic syndrome characterized by nausea, vomiting, and blood diarrhea in adults.8Pandey, Y., Atwal, D., & Sasapu, A. (2019). Diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in adults: two case reports and review of the literature. Cureus, 11(4).

Gastrointestinal Symptoms:

In addition to bloody diarrhea, HUS patients experience other gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain. Mostly, headaches and abdominal pains accompany feelings of nausea and vomiting.9Tome, J., Maselli, D. B., Im, R., Amdahl, M. B., Pfeifle, D., Hagen, C., & Halland, M. (2022). A case of hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli after pericardiectomy. Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology, 1-5. These are common HUS symptoms in multiple clinical cases of HUS.10Borkowska, A., Sobstyl, A., Chałupnik, A., Chilimoniuk, Z., Dobosz, M., & Marosz, S. (2020). Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS)–case report. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 10(9), 431-435. Abdominal pain occurs in around 29% of cases. There may also be cramping and bloating in the stomach area.

Headache:

One of the most prevalent symptoms of the Hemolytic syndrome is headache. Several times, patients present to the ER with complaints of headache and nausea. One time, a 28-year-old female patient presented with a headache and blurred vision. Investigations revealed thrombocytopenia and uncontrolled hypertension. The hike in blood pressure and acute kidney injury persisted despite rapid blood pressure control maneuvers. The patient was quickly diagnosed as an atypical HUS patient. Quick treatment saved her life.11Fakhouri, F., Schwotzer, N., & Frémeaux-Bacchi, V. (2023). How I diagnose and treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 141(9), 984-995. Therefore, experts advise doctors to consider headaches an evident HUS symptom.

Fever:

Pyrexia (fever) is a classic feature of the vast majority of infectious diseases. Fever and chills are the chief complaints of patients. Around 37% of typical HUS patients suffer from fever and abdominal pain.

Cardiovascular Issues:

Abnormalities in the cardiovascular system are not uncommon in HUS patients (occur in 3-10% of aHUS cases). Children with the atypical type of HUS are more likely to have cardiac involvement. Thrombotic microangiopathy caused by the syndrome leads to diffuse microthrombi, potentially damaging the heart’s microvascular network.

Studies show that the following symptoms are commonly encountered:12Filip, C., Nicolescu, A., Cinteza, E., Duica, G., Nicolae, G., Safta-Baschieru, D., … & Balgradean, M. (2020). Cardiovascular complications of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Maedica, 15(3), 305.

Hypertension

Arterial hypertension is seen in almost half of the cases with cardiovascular complications.

Arrhythmia

There have been multiple cases of heart rhythm abnormalities (mostly rapid heart rates), especially in children.13Kavgacı, A., Leventoğlu, E., Azapağası, E., Serdaroğlu, E., Fidan, K., & Kula, S. (2024). Cardiac Manifestation in a Child With Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Clinical Pediatrics, 00099228231223656. Other complications such as infarcts (due to thrombosis) may lead to sudden death.

Pulmonary Complications:

In addition to the cardiovascular issues, patients may also face pulmonary complications. The microthrombi produced by vessel damage can lead to pulmonary embolism, hemorrhage, etc. This may present as dyspnea (shortness of breath). Additionally, pulmonary arterial hypertension is a serious complication that can lead to death if left untreated/poorly treated.

Skin Changes:

Many patients notice changes in the color of their skin. Some report generalized skin bruising (without any significant cause), while others are worried about skin pallor. Very rarely, HUS leads to skin lesions. However, a clinical study highlighted three cases of skin lesion development attributed to atypical HUS. Dark brown pigmentation of the skin was suspected to be caused by hemolytic microangiopathies.14Ardissino, G., Tel, F., Testa, S., Marzano, A. V., Lazzari, R., Salardi, S., & Edefonti, A. (2014). Skin involvement in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. American journal of kidney diseases, 63(4), 652-655. Skin changes are one of the extra-renal manifestations of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome.15Formeck, C., & Swiatecka-Urban, A. (2019). Extra-renal manifestations of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatric Nephrology, 34, 1337-1348.

CNS Symptoms:

Acute severe neurological involvement is considered the most threatening complication of HUS in children. Encephalopathy, hemorrhagic stroke, and brain infarcts are common issues.16Brown, C. C., Garcia, X., Bhakta, R. T., Sanders, E., & Prodhan, P. (2021). Severe acute neurologic involvement in children with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Pediatrics, 147(3).

Confusion

In the old days, physicians believed there was no link between CNS symptoms and HUS. However, now, it is a fact that CNS presentations like confusion are seen in atypical HUS patients.17Berger, B. E. (2019). Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a syndrome in need of clarity. Clinical Kidney Journal, 12(3), 338-347.

Seizures

Neurological symptoms like seizures may indicate underlying hemolytic uremic syndrome. Children with atypical HUS are prone to having seizures due to HUS.18Chan, S., & Weinstein, A. R. (2019). Seizure as the presenting symptom for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 56(4), 441-443.

Stroke

Hemorrhagic stroke is a rare manifestation of atypical HUS. There have been reports of catastrophic hemorrhagic stroke in young female patients. Therefore, timely treatment is a dire need for atypical HUS patients.19Fida, S., & Sharma, S. (2024). Unprecedented Haemorrhagic Stroke: A Rare Manifestation of Atypical Haemolytic Syndrome. Cureus, 16(9).

Encephalopathy

Uremic encephalopathy is a serious manifestation of acute kidney injury. Encephalopathy encompasses a range of conditions that cause brain dysfunction (memory, cognitive loss, confusion, etc.).

Renal Failure (Severe Symptoms):

The main target of the disorder is the kidneys. Therefore, the greatest implications are seen in renal health and function. Typical HUS is notorious for causing acute kidney injury in 70% of the patients. However, with timely treatment, 70-85% of such patients recover proper kidney function. On the other hand, atypical HUS has poor outcomes, with around 50% of patients progressing to end-stage renal disease (and/or associated irreversible brain damage). Unfortunately, renal damage proves to be fatal for about 25% of the patients. Renal consequences of hemolytic uremic syndrome include:

Urine abnormalities

Many patients report a reduced urine volume (oliguria). There can be a mixing of blood with urine, a condition called hematuria.

Uremia

When the kidney loses its function, there is an increase in waste products and toxins within the body i.e., uremia.

Edema

Progressive kidney failure leads to fluid buildup, especially in the legs, feet, and ankles (pedal edema). However, this is a rare finding.

What Causes Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome?

Infection:

The most prevalent type of HUS, typical HUS, results from bacterial infection. Specific strains of the Escherichia coli (Shiga toxin-producing E. Coli or STEC) bacteria cause disease in children and adults. E. coli 0157: H7 is a major cause of the disease as it produces Shiga toxin.

This toxin enters your bloodstream and induces cytotoxic effects, destroying red blood cells and damaging your kidneys. Another Shiga toxin-producing strain that can cause HUS is E. coli 026: H11. Shiga toxin has two disease-causing subtypes, Stx 1 and Stx 2. The latter type is notorious for causing a more severe form of disease. Thus, people affected with Stx 2 require better treatment and renal replacement therapy.

This toxin enters your bloodstream and induces cytotoxic effects, destroying red blood cells and damaging your kidneys. Another Shiga toxin-producing strain that can cause HUS is E. coli 026: H11. Shiga toxin has two disease-causing subtypes, Stx 1 and Stx 2. The latter type is notorious for causing a more severe form of disease. Thus, people affected with Stx 2 require better treatment and renal replacement therapy.

Some non-STEC infections can also contribute to HUS. The most common examples include:

- Shigella dysenteriae

- Streptococcus pneumonia

- Salmonella typhi

How Can You Get Infected With Shiga-Toxin Producing E. Coli (STEC)?

You are likely to become a victim of the merciless STEC bacteria if you eat undercooked meat or drink unpasteurized milk. Uncooked ground beef20Barlow, R. S., Gobius, K. S., & Desmarchelier, P. M. (2006). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef and lamb cuts: results of a one-year study. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 111(1), 1-5. and unpasteurized raw milk may contain harmful pathogens, including STEC.21Artursson, K., Schelin, J., Lambertz, S. T., Hansson, I., & Engvall, E. O. (2018). Foodborne pathogens in unpasteurized milk in Sweden. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 284, 120-127. Eating contaminated fruits and vegetables (without properly washing them) may also land you in trouble.

Is Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Contagious?

The disease (HUS) itself isn’t contagious. However, the bacteria E. coli is contagious and can cause HUS. You can acquire the disease-causing bacteria if you come in contact with a contaminated person’s body (or feces).

Genetic Mutations:

Around fifty mutations have been identified in connection with hemolytic uremic syndrome.

However, experts believe that a major cause of atypical HUS is a mutation in the CFH gene that leads to abruptions in the alternative complement pathway. This particular gene encodes for factor H which is a main regulatory protein of the alternative complement pathway. Sometimes, a second inciting agent (such as an infection) acts as a trigger for faults in the complement system.

However, experts believe that a major cause of atypical HUS is a mutation in the CFH gene that leads to abruptions in the alternative complement pathway. This particular gene encodes for factor H which is a main regulatory protein of the alternative complement pathway. Sometimes, a second inciting agent (such as an infection) acts as a trigger for faults in the complement system.

Secondary To Other Conditions:

Medicines/drugs

Different types of drugs can contribute to secondary HUS. Anti-malaria drugs like quinine and immunosuppressants (such as interferons, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, etc.) may lay the foundation for HUS.

Cancer Therapy

Anti-cancer chemotherapy drugs like bleomycin, cisplatin, carfilzomib, etc. can cause secondary hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Drug abuse

Overuse and abuse of drugs like cocaine, oxymorphone (morphine), and ecstasy (pills) can trigger HUS.

High-Risk Groups:

The following individuals are at a greater risk of developing HUS:

- Infants and children under the age of 5.

- People with a family history of atypical HUS.

- Inhabitants of areas with prevalent E. coli infection.

- Immunocompromised patients (mostly patients on immunosuppressants).

How To Diagnose Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome?

History & Physical Examination:

Your healthcare provider will start with your medical history. Abdominal cramping and painful diarrhea are common initial complaints of young patients (1-10 days after exposure).

A family history of hemolytic uremic syndrome and a physical examination of the patient are important.

Diagnostic Tests:

If your doctor suspects hemolytic uremic syndrome, he may order the following tests:

Urine Analysis

Professionals look for blood cells and protein in a provided sample of urine.

Stool test

You will be given a container to collect feces. Lab technicians then detect the presence of the bacteria E. coli 0157 in the sample to diagnose typical HUS.

Blood test

Your doctor will most likely order multiple blood tests to diagnose the hemolytic syndrome.

- A complete blood count (CBC) reveals a reduced red blood cell and a raised white blood cell count.

- Platelet count is reduced.

- Blood clotting profiles may reveal changes in prothrombin and thromboplastin time.

- Blood smear shows broken down, fragmented red blood cells.

Genetic Testing

This is a type of blood cell in which lab technicians determine the tendency of a patient to inherit HUS due to their genetic makeup. This is mostly done in suspected aHUS cases.

Very rarely, a kidney biopsy is performed to investigate kidney function in adult patients with advanced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Sometimes doctors order a Coombs Test to rule out kidney failure due to some other causes. Coombs test is negative for hemolytic uremic syndrome and a positive Coombs test generally indicates underlying auto-immune hemolytic anemia.

Differential Diagnosis:

Shigella dysenteriae is known to produce Shiga toxin and causes a disease similar to HUS. However, Shigella infection is much more severe and has a higher fatality rate than HUS. Other conditions similar to HUS include:

- Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Purpura (TTP)

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)

- HELLP syndrome (in pregnant women)

- Systemic Vasculitis

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Treatment

Loss of body fluid volume is a grave consequence of the disorder. Therefore, the main of supportive therapy is to replenish fluids. Doctors usually employ the following therapies:

IV Fluid Therapy

Healthcare professionals maintain an IV line to replenish and keep you hydrated. Some patients may also require parenteral nutrition (feeding through a tube).

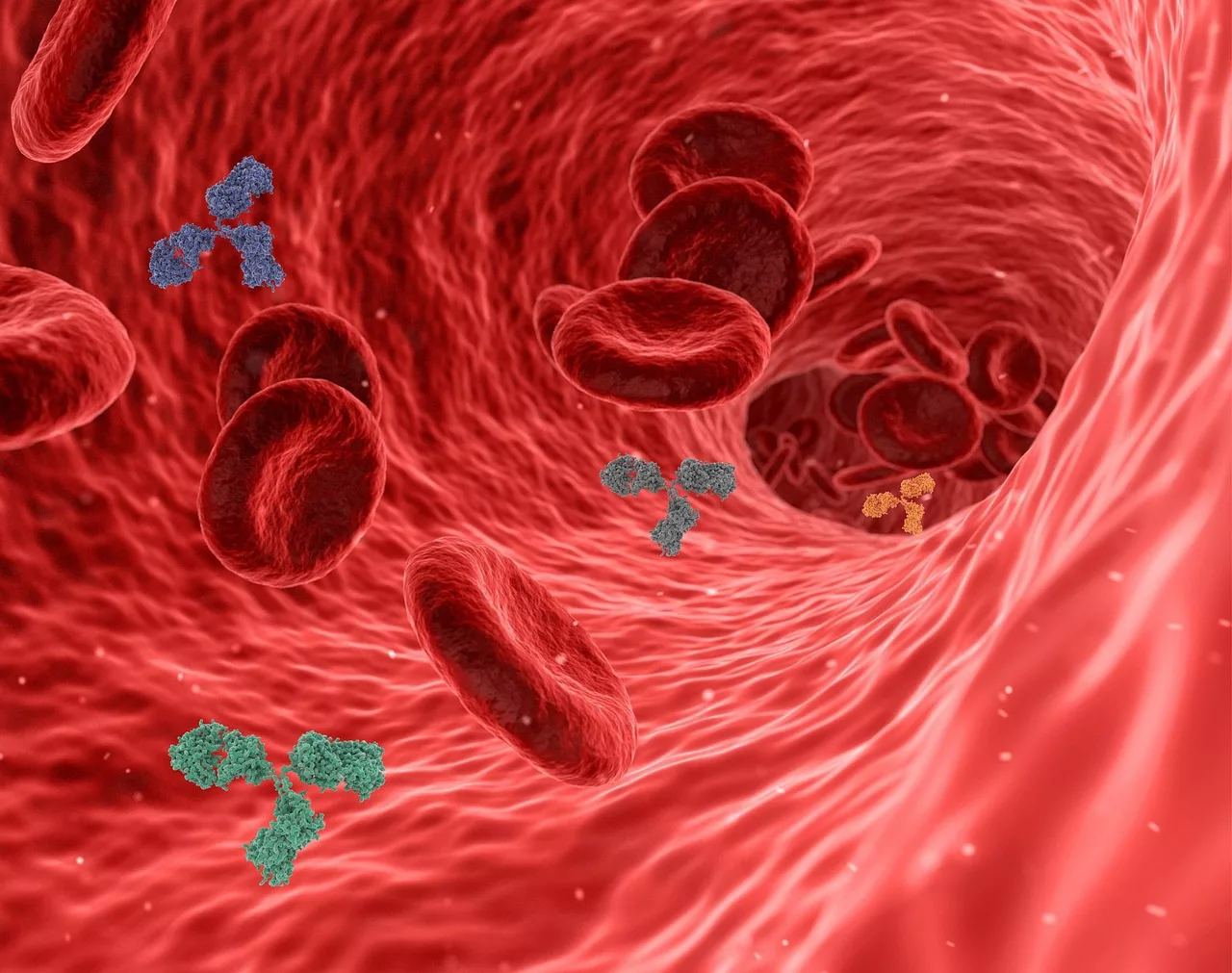

Blood Transfusion

As hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia ensue with HUS, blood transfusion is necessary to maintain normal blood count and alleviate symptoms (like shortness of breath, tachycardia, and bruising).

Medications

Doctors usually advise anti-motility agents (to manage diarrhea) and antibiotics (in typical STEC-induced HUS cases). In most cases, healthcare providers advise 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy.

In atypical HUS patients, the main aim of treatment is to prevent end-stage renal disease. Therefore, the first line of therapy is eculizumab or ravulizumab (monoclonal antibodies targeting specific complement system components). Modern studies show patient preference for ravulizumab over eculizumab.22Mauch, T. J., Chladek, M. R., Cataland, S., Chaturvedi, S., Dixon, B. P., Garlo, K., … & Wang, Y. (2023). Treatment preference and quality of life impact: ravulizumab vs eculizumab for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 12(9), e230036. These drugs are effective in managing the disease, and the majority of doctors advocate their use.

An important point to note here is that these monoclonal antibodies increase your chances of meningococcal and pneumococcal disease. Therefore, doctors strictly advise getting vaccinations before the start of therapy.

Patients with poor renal function are advised of dialysis.

How Good Is The Treatment Prognosis & Patient Recovery?

Recovery from hemolytic uremic syndrome is good, and treatment prognosis is good for the typical type. As per estimations, more than 80% of patients with HUS make complete recovery, while around 25% of adults develop long-term kidney insufficiency. Advancements in antibody therapy (eculizumab, etc.) have reduced HUS-related death from 30-50% in children down to 9%, and in adults, the numbers have successfully fallen from 60% to 15%.23Palma, L. M. P., Vaisbich-Guimarães, M. H., Sridharan, M., Tran, C. L., & Sethi, S. (2022). Thrombotic microangiopathy in children. Pediatric Nephrology, 37(9), 1967-1980.

How Can I Prevent HUS?

You can adopt the following steps to prevent exposure to STEC and, consequently, HUS:

- Thoroughly wash your utensils and hands (with soap) before consuming food.

- Avoid drinking unpasteurized drinks and eating uncooked/undercooked meat.

- Avoid swimming in a public pool if you have diarrhea.

Final Word

Hemolytic uremic syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by a breakdown of blood cells due to endothelial (vessel) damage in the kidneys. It compromises kidney function and leads to complications in multiple systems. Bloody diarrhea, headache, fever, cardiac symptoms, skin changes, and renal failure are the most evident symptoms. Typical HUS is caused by specific E. coli bacteria (STEC) strains, while atypical type is inherited from parents. Shiga toxin from STEC destroys vessels. Most victims are children below 5 years of age. Treatment involves fluid replacement therapy, blood transfusions, antibiotics, and dialysis (in severe kidney failure). Treatment prognosis is good, and most patients make a full recovery.

Refrences

- 1Aldharman, S. S., Almutairi, S. M., Alharbi, A. A., Alyousef, M. A., Alzankrany, K. H., Althagafi, M. K., … & Jamil, S. F. (2023). The prevalence and incidence of hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review. Cureus, 15(5).

- 2Joseph, A., Cointe, A., Mariani Kurkdjian, P., Rafat, C., & Hertig, A. (2020). Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: A narrative review. Toxins, 12(2), 67.

- 3Harboe, M., & Mollnes, T. E. (2008).The alternative complement pathway revisited. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 12(4), 1074-1084.

- 4Gupta, M., Govindappagari, S., & Burwick, R. M. (2020). Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 135(1), 46-58.

- 5Saad, A. F., Roman, J., Wyble, A., & Pacheco, L. D. (2016). Pregnancy-associated atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. American Journal of Perinatology Reports, 6(01), e125-e128.

- 6Barrera‐Hoffmann, C., Mariaca‐Ortíz, Y., Ruiz‐Villa, J. G., Cuevas‐Cruz, L. E., López‐Mendoza, M. D. R., & Briones‐Garduño, J. C. (2024). Pregnancy‐associated atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Case report. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research.

- 7Viteri, B., & Saland, J. M. (2020). Hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatrics In Review, 41(4), 213-215.

- 8Pandey, Y., Atwal, D., & Sasapu, A. (2019). Diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in adults: two case reports and review of the literature. Cureus, 11(4).

- 9Tome, J., Maselli, D. B., Im, R., Amdahl, M. B., Pfeifle, D., Hagen, C., & Halland, M. (2022). A case of hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli after pericardiectomy. Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology, 1-5.

- 10Borkowska, A., Sobstyl, A., Chałupnik, A., Chilimoniuk, Z., Dobosz, M., & Marosz, S. (2020). Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS)–case report. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 10(9), 431-435.

- 11Fakhouri, F., Schwotzer, N., & Frémeaux-Bacchi, V. (2023). How I diagnose and treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 141(9), 984-995.

- 12Filip, C., Nicolescu, A., Cinteza, E., Duica, G., Nicolae, G., Safta-Baschieru, D., … & Balgradean, M. (2020). Cardiovascular complications of hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Maedica, 15(3), 305.

- 13Kavgacı, A., Leventoğlu, E., Azapağası, E., Serdaroğlu, E., Fidan, K., & Kula, S. (2024). Cardiac Manifestation in a Child With Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Clinical Pediatrics, 00099228231223656.

- 14Ardissino, G., Tel, F., Testa, S., Marzano, A. V., Lazzari, R., Salardi, S., & Edefonti, A. (2014). Skin involvement in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. American journal of kidney diseases, 63(4), 652-655.

- 15Formeck, C., & Swiatecka-Urban, A. (2019). Extra-renal manifestations of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatric Nephrology, 34, 1337-1348.

- 16Brown, C. C., Garcia, X., Bhakta, R. T., Sanders, E., & Prodhan, P. (2021). Severe acute neurologic involvement in children with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Pediatrics, 147(3).

- 17Berger, B. E. (2019). Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a syndrome in need of clarity. Clinical Kidney Journal, 12(3), 338-347.

- 18Chan, S., & Weinstein, A. R. (2019). Seizure as the presenting symptom for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 56(4), 441-443.

- 19Fida, S., & Sharma, S. (2024). Unprecedented Haemorrhagic Stroke: A Rare Manifestation of Atypical Haemolytic Syndrome. Cureus, 16(9).

- 20Barlow, R. S., Gobius, K. S., & Desmarchelier, P. M. (2006). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef and lamb cuts: results of a one-year study. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 111(1), 1-5.

- 21Artursson, K., Schelin, J., Lambertz, S. T., Hansson, I., & Engvall, E. O. (2018). Foodborne pathogens in unpasteurized milk in Sweden. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 284, 120-127.

- 22Mauch, T. J., Chladek, M. R., Cataland, S., Chaturvedi, S., Dixon, B. P., Garlo, K., … & Wang, Y. (2023). Treatment preference and quality of life impact: ravulizumab vs eculizumab for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 12(9), e230036.

- 23Palma, L. M. P., Vaisbich-Guimarães, M. H., Sridharan, M., Tran, C. L., & Sethi, S. (2022). Thrombotic microangiopathy in children. Pediatric Nephrology, 37(9), 1967-1980.