Hereditary Hemochromatosis is an inherited iron overload disorder characterized by excessive iron absorption due to hepcidin deficiency. There are four different types of hereditary hemochromatosis, classified based on age of onset and genetic factors. Early symptoms of the condition are typically mild, but they can become severe as the disease progresses. These symptoms are affected by lifestyle and environmental factors. As it is a genetic disorder, gene mutation is the main cause of this syndrome. Diagnosis is made through several tests, and treatment of this ailment requires the removal of excess iron from the body.1Kowdley, K. V., Brown, K. E., Ahn, J., & Sundaram, V. (2019). ACG clinical guideline: hereditary hemochromatosis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 114(8), 1202-1218.

What is Hereditary Hemochromatosis?

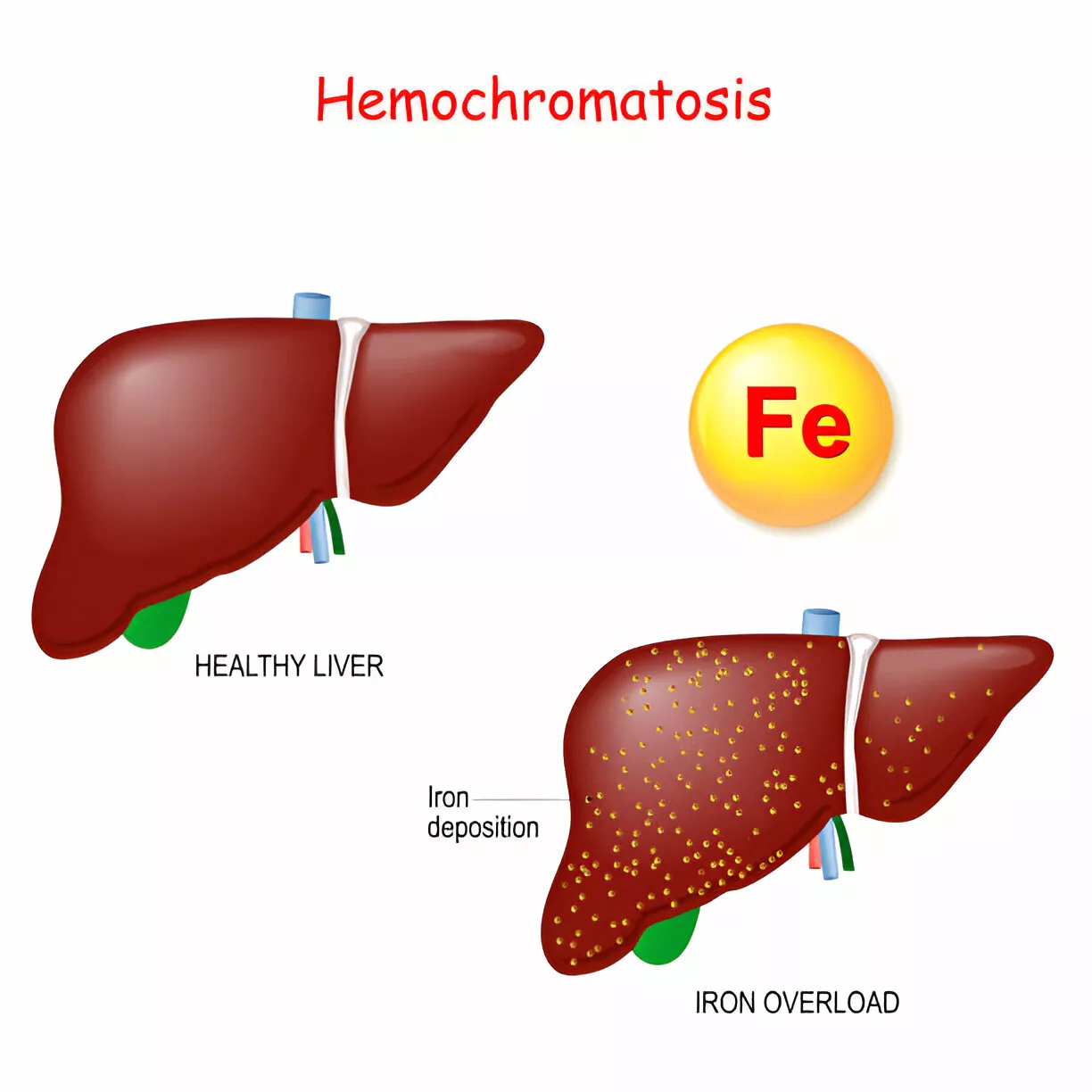

Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder in which too much iron builds up in the body. While iron is essential for body function, too much of it can be harmful. The excess iron deposits in the parenchymal cell lead to cellular dysfunction. The most commonly involved organs are the pituitary gland, skin, heart, joints, liver, and pancreas. The regulation of iron levels in the body primarily occurs through intestinal absorption.2Kane, S. F., Roberts, C., & Paulus, R. (2021). Hereditary hemochromatosis: rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 104(2), 263-270..

HH is the most prevalent autosomal recessive disorder among white individuals, affecting approximately 1 in every 300 to 500 people.3Adams PC. Epidemiology and diagnostic testing for hemochromatosis and iron overload. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015 May;37 Suppl 1:25-30. This disease’s highest prevalence occurs in people with Scandinavian and Irish ancestry. However, this mutation is rare in the people of Africa, Asia, Pacific, and Hispanic Islander ancestry. The prevalence of hereditary hemochromatosis in men and women is equal.4Kowdley, K. V., Brown, K. E., Ahn, J., & Sundaram, V. (2020). ACG Clinical Guideline: Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Clinical Liver Disease, 16(5), 177-177.

Pathophysiology of Hereditary Hemochromatosis

Hereditary hemochromatosis is a genetic disorder that occurs when the body’s ability to sense and regulate iron levels is impaired. Normally, the hormone hepcidin helps control iron absorption and release from cells. In people with hereditary hemochromatosis, the body does not produce enough hepcidin in response to high iron levels. As a result, too much iron is absorbed from the intestines and released from cells, leading to increased iron in the bloodstream and accumulation in various organs. This iron overload can cause damage to tissues over time. The exact processes that affect hepcidin production in this disorder are still being studied.5Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L., Świątczak, M., Sikorska, K., Starzyński, R. R., Raczak, A., & Lipiński, P. (2021). Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical implications of hereditary hemochromatosis—the cardiological point of view. Diagnostics, 11(7), 1279..

Causes of Hereditary Hemochromatosis

This iron overload in your body can be caused by variations in one of the genes regulating how your body absorbs iron from food. The most commonly involved gene is called HFE (“H” stands for high or hereditary, and “Fe” stands for iron). The most common mutation in this gene is C282Y. Inheriting one copy of the C282Y mutation from each parent (homozygous C282Y) or one C282Y and one H63D mutation (compound heterozygous C282Y/H63D) on chromosome 6 accounts for about 95% of hereditary hemochromatosis cases.

These genetic mutations are typically inherited from both parents.6Test, H. T. U. T. (2023). Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HFE Related). If you inherit one gene, you are unlikely to develop hemochromatosis, but you will be considered a carrier of the mutation. You can pass the altered gene to your children. Your children can develop the condition only if they inherit another altered gene from their other parent. Not everyone who inherits two genes develops complications related to iron overload of hemochromatosis.

Types of Hereditary Hemochromatosis

This condition has the following types:

Type-1:

Type-1 hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common type of this disorder. It is also known as HFE-related hemochromatosis. Type 1 is caused by the H63D and C282Y mutations of the HFE gene on chromosome 6. It is characterized by the excessive intestinal absorption of dietary iron. The onset of this type is after menopause in females, while in men, these symptoms develop between 40 and 60. Mostly, it remains asymptomatic throughout life unless the environmental or genetic factors contribute to excessive iron accumulation.

Type-2:

Type-2 hereditary hemochromatosis, also known as juvenile-onset hemochromatosis, typically presents with symptoms in childhood or early adulthood, often between the ages of 15 and 20. This form of hemochromatosis is associated with mutations in the HJV (hemojuvelin) and HAMP (hepcidin) genes, which play critical roles in regulating iron absorption and metabolism. Iron accumulation at age 20 causes the absence or decreased secretion of sex hormones in the body. Males experience symptoms related to the shortage of sex hormones or delayed puberty. Affected females do not get menstruation on time, or menstruation begins normally but stops after a few years. It is the following subtypes:

- Type 2a: Caused by mutations in the HJV (hemojuvelin) gene.

- Type 2b: Results from mutations in the HAMP (hepcidin) gene.

Type-3:

Mutations in the transferrin receptor gene cause this type. Type-3 hereditary hemochromatosis symptoms begin before the age of 30 (the onset of this disorder is generally intermediate between type 1 and type 2). In type-3 hereditary hemochromatosis, the reduced expression of hepcidin due to mutation causes increased intestinal iron absorption and excessive release from the spleen. Approximately the number of affected individuals with this condition in the world was only 50, and they were from Italy, Portugal, and Japan.7Kane, S. F., Roberts, C., & Paulus, R. (2021). Hereditary hemochromatosis: rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 104(2), 263-270.

Type-4:

Type 4 of this disease is also known as ferroportin disorder, as it affects the ferroportin. Ferroportin is an iron transport protein needed to export iron from cells to the circulation. It is caused by the mutations of the SLC40A1 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 2. This disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. This type can begin any time from childhood to adulthood (10-80 years). Although this ailment is rare, it is found worldwide.8Palmer, W. C., Zaver, H. B., & Ghoz, H. M. (2020). How I approach patients with elevated serum ferritin. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 115(9), 1353-1355.

Signs & Symptoms of Hereditary Hemochromatosis

The trickiest part about this disorder is that it mostly goes undetected for several years. Its symptoms can be subtle and mimic other conditions as well. The symptoms often develop slowly and may not become apparent until later in life. Common symptoms include:

General Symptoms

Apathy, fatigue, weakness, malaise, and weight loss.

Joint Issues

Decreased grip strength, arthralgia, arthritis, boggy and tender joints. Researchers do not completely understand the causes of joint pain in this condition, but they believe excess iron in the body causes calcium crystals to accumulate in the joint spaces.The commonly affected joints are the knuckles of the 2nd and 3rd fingers of the hands.

Skin Changes

Bronzing, spider angiomas, and jaundice. Along with the pigment melanin, iron in the skin can give a person a tanned appearance. Deposits of iron in the skin can darken it and sometimes cause the skin to look grey. Doctors often refer to hemochromatosis as “bronze diabetes” because it causes characteristic skin discoloration and is associated with diabetes, resulting from iron overload damaging the pancreas.

Heart Problems

Excess iron can cause heart enlargement (Cardiomegaly). It can also interfere with the normal electrical conduction system of the heart and can affect its rhythmic movement. Heart failure is also evident in some severe cases. However, in some rare cases, the first signs of this disorder begin with the heart.9Kane, S. F., Roberts, C., & Paulus, R. (2021). Hereditary hemochromatosis: rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 104(2), 263-270.

Endocrine Issues

This includes Hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus, hypopituitarism, and hypothyroidism. If the excess iron accumulates in the pancreas, it can interfere with insulin production and can lead to diabetes mellitus. Similarly, the deposition of iron in the thyroid gland can lead to hypothyroidism.

Liver Complications

The hepatic complications include Fibrosis, ascites, hepatomegaly, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The liver is the main organ in your body that stores iron. Excessive accumulation of iron in your liver can result in abnormality in the function of the liver and liver fibrosis. At the diagnosis, most of the patients have abnormal liver function. The iron overload can also lead to cirrhosis. Cirrhosis can ultimately result in liver failure or even death. People with cirrhosis are at increased risk of developing liver cancer.

Reproductive

Testicular atrophy, impotence, decreased libido, and amenorrhea.10Salgia, R. J., & Brown, K. (2015). Diagnosis and management of hereditary hemochromatosis. Clinics in liver disease, 19(1), 187-198.

Infections

This condition can raise the risk of infections with certain kinds of bacteria. It happens when an accumulation of iron disrupts the immune system’s ability to fight off certain types of bacteria.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis begins with a detailed history and examination. A healthcare provider will assess the patient’s symptoms, family history, and any signs consistent with iron overload, such as diabetes, skin changes, or joint pain. Definitive diagnosis involves a series of tests. These diagnostic tests help differentiate this condition from other ailments and can also aid in determining the severity of the disorder and its complications.

Genetic Tests:

Genetic testing is required to reveal the HFE C282Y variant linked with hereditary hemochromatosis. Another variant seen in some rare cases is the H63D, as mentioned above. However, genetic testing has been reported to be very controversial and has limited relevance to H63D with this condition.11Salgia, R. J., & Brown, K. (2015). Diagnosis and management of hereditary hemochromatosis. Clinics in liver disease, 19(1), 187-198.

Blood Tests:

Two blood tests are recommended to assess the amount of excess iron in the body. These are:

Ferritin Level Testing

When the body stores iron, ferritin levels increase. The levels of this protein do not upsurge until iron stores are too high. In the early course of hemochromatosis, this test can be normal. Elevated ferritin levels, typically above 200 ng/mL in females and 300 ng/mL in males, can support the diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis. However, it’s important to note that elevated ferritin levels alone are not definitive for diagnosis and should be interpreted with other tests and clinical evaluations.12Brissot, P., Pietrangelo, A., Adams, P. C., De Graaff, B., McLaren, C. E., & Loréal, O. (2018). Hemochromatosis. Nature reviews Disease primers, 4(1), 1-15.

Transferrin Saturation

The transferrin saturation test assesses the amount of iron bound to transferrin, which rises as the iron store rises. A value higher than 45% should be taken as an indicator for further evaluation. This is the most sensitive test for hemochromatosis diagnosis. “Total iron binding capacity (TIBC)” also measures the same. Once blood tests confirm excess iron in the body, some other tests are required to determine the amount of iron deposited in tissues such as the heart and liver.

Liver Biopsy:

This test is not required in many simple cases. Although less common, a liver biopsy can assess the degree of iron accumulation in the liver and detect any liver damage or fibrosis.

Transient Elastography

This is a non-invasive method. It is mainly used to determine the extent of cirrhosis.

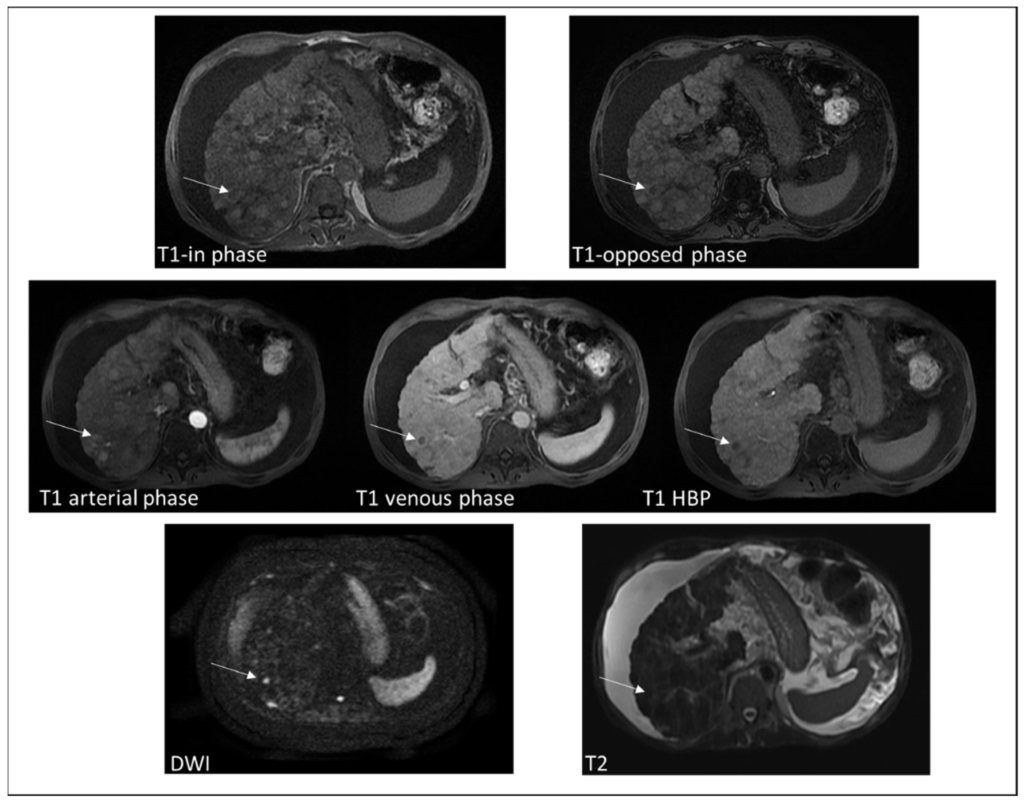

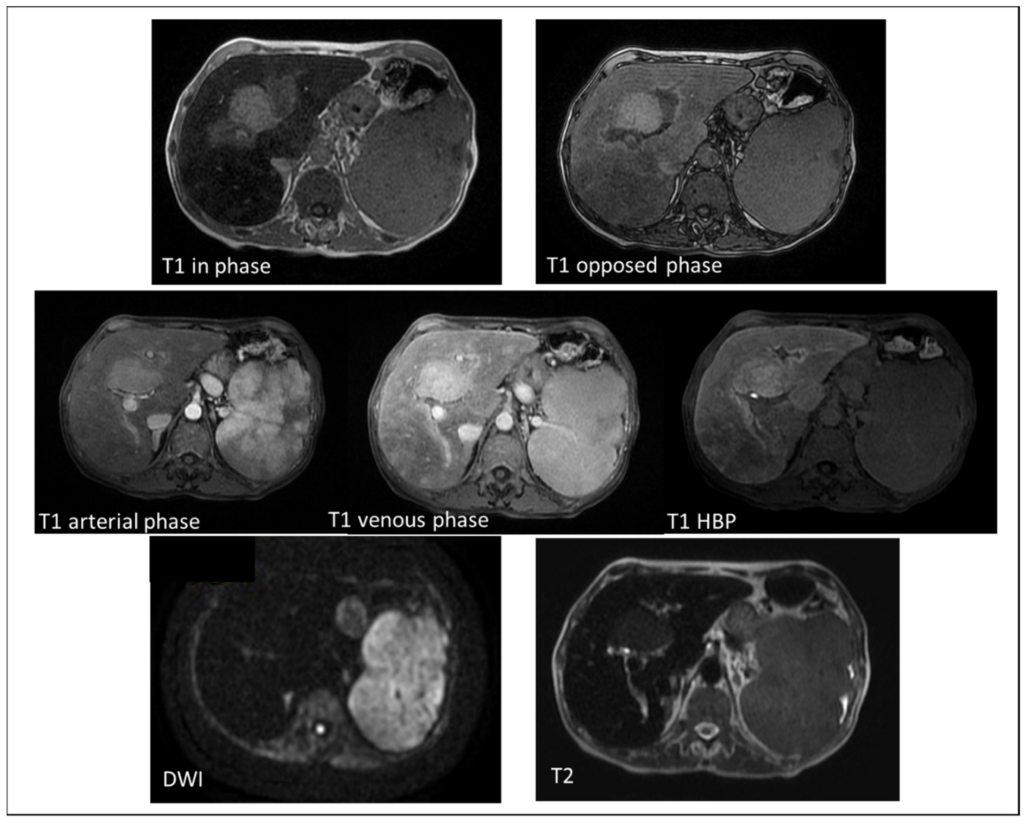

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI techniques, such as T2*, R2, and R2*, are useful for assessing iron accumulation in the body. MRI is commonly employed to visualize and evaluate iron deposits in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. These imaging methods can provide detailed information about the extent and distribution of iron overload in various organs, such as the liver and heart.

Hereditary Hemochromatosis Treatment

The good news is that this condition is manageable with proper treatment. Treatment of hereditary hemochromatosis involves different therapies and modifications. Let’s talk about them one by one.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Some lifestyle changes can aid in treating this disorder:

- Vitamin C increases iron absorption, so avoid using vitamin C supplements

- Try to avoid multivitamins that contain iron and iron supplements, as these can increase your body’s iron level.

- Raw fish and shellfish have certain bacteria that can cause infections in people suffering from hemochromatosis.

- Avoid alcohol completely if you already have a liver disease and you are a hemochromatosis patient.

Phlebotomy:

Phlebotomy is the primary treatment for managing iron overload. This involves the periodic removal of blood to reduce iron levels. Initially, you may need to have a pint of blood removed once or twice a week. During the procedure, a healthcare provider inserts a needle into a vein in your arm and collects blood into a bag. As your iron levels decrease, the provider will reduce the frequency of your phlebotomy sessions, depending on how quickly your iron levels normalize. However, phlebotomy may not be suitable if you have certain conditions like heart disease or anemia.

Iron Chelation Therapy:

In cases where phlebotomy is not suitable, such as with certain medical conditions, iron chelation therapy may be used. This involves using medications that bind to excess iron and help remove it from the body.

Surgical Therapy:

Liver transplantation is considered for patients who develop end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma liver disease. This will normalize hepcidin secretion and avoid the recurrence of hepatic iron overload.13Bardou‐Jacquet, E., Philip, J., Lorho, R., Ropert, M., Latournerie, M., Houssel‐Debry, P., … & Brissot, P. (2014). Liver transplantation normalizes serum hepcidin levels and cures iron metabolism alterations in HFE hemochromatosis. Hepatology, 59(3), 839-847. Regular monitoring of iron levels through blood tests is essential to ensure effective management. Monitoring for complications, such as diabetes, liver disease, and heart problems, is also crucial.

Conclusion

Living with hereditary hemochromatosis needs lifestyle adjustments and ongoing monitoring. You need to stay vigilant about your health. This genetic disorder requires awareness, early detection, and active management. Always remember! Knowledge is a power when it comes to hereditary hemochromatosis. So, stay tuned, stay informed, stay proactive, and take charge of your health journey.

Refrences

- 1Kowdley, K. V., Brown, K. E., Ahn, J., & Sundaram, V. (2019). ACG clinical guideline: hereditary hemochromatosis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 114(8), 1202-1218.

- 2Kane, S. F., Roberts, C., & Paulus, R. (2021). Hereditary hemochromatosis: rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 104(2), 263-270.

- 3Adams PC. Epidemiology and diagnostic testing for hemochromatosis and iron overload. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015 May;37 Suppl 1:25-30.

- 4Kowdley, K. V., Brown, K. E., Ahn, J., & Sundaram, V. (2020). ACG Clinical Guideline: Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Clinical Liver Disease, 16(5), 177-177.

- 5Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L., Świątczak, M., Sikorska, K., Starzyński, R. R., Raczak, A., & Lipiński, P. (2021). Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical implications of hereditary hemochromatosis—the cardiological point of view. Diagnostics, 11(7), 1279.

- 6Test, H. T. U. T. (2023). Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HFE Related).

- 7Kane, S. F., Roberts, C., & Paulus, R. (2021). Hereditary hemochromatosis: rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 104(2), 263-270.

- 8Palmer, W. C., Zaver, H. B., & Ghoz, H. M. (2020). How I approach patients with elevated serum ferritin. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 115(9), 1353-1355.

- 9Kane, S. F., Roberts, C., & Paulus, R. (2021). Hereditary hemochromatosis: rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 104(2), 263-270.

- 10Salgia, R. J., & Brown, K. (2015). Diagnosis and management of hereditary hemochromatosis. Clinics in liver disease, 19(1), 187-198.

- 11Salgia, R. J., & Brown, K. (2015). Diagnosis and management of hereditary hemochromatosis. Clinics in liver disease, 19(1), 187-198.

- 12Brissot, P., Pietrangelo, A., Adams, P. C., De Graaff, B., McLaren, C. E., & Loréal, O. (2018). Hemochromatosis. Nature reviews Disease primers, 4(1), 1-15.

- 13Bardou‐Jacquet, E., Philip, J., Lorho, R., Ropert, M., Latournerie, M., Houssel‐Debry, P., … & Brissot, P. (2014). Liver transplantation normalizes serum hepcidin levels and cures iron metabolism alterations in HFE hemochromatosis. Hepatology, 59(3), 839-847.