Infant Botulism is an intestinal toxemia that results from the ingestion of spores of the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. C. botulinum is a gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus. The estimated lethal dose for humans is in the nanogram per kilogram range (ng/kg), highlighting the extreme potency of the toxin.1Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

Infants below the age of one year and those exposed to the environmental spores of the bacterium or honey have the highest risk of contracting the disease due to the immature gut microbiota. Around 100 cases of infant botulism are reported annually in the United States. Health authorities strongly advise against feeding honey to infants under one year. Up to 20% of infant botulism cases in the United States have been linked to honey consumption.2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Infant Botulism FAQs. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/infant-botulism.html3Pickett, J., & Berg, B. (1992). Infant botulism: A public health perspective. American Public Health Association.

The first and most consistent symptom is constipation, followed by progressive muscle weakness, starting with poor feeding, weak cry, facial weakness, and eventually descending flaccid paralysis. In severe cases, respiratory muscles may be affected, necessitating mechanical ventilation.

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, and prompt treatment with Botulism Immune Globulin Intravenous (BIG-IV) significantly improves outcomes. Parental awareness is crucial, as infants cannot communicate symptoms, and early signs are often subtle.

Causes of Infant Botulism

-

Children develop infant botulism when they ingest spores of the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Honey is one of the best-known sources of these spores, which is why it is not recommended for babies under one year of age. While milk itself is not a direct cause, contaminated feeding practices or utensils might introduce spores. In most cases, however, experts are unable to trace the exact source of infection.

- A, B, and E are known to cause illness in humans. Among these, Types A and B are responsible for nearly all reported cases of infant botulism.4Lyons-Warren, A.M., S.R. Risen, and G. Clark, Infant Botulism With Asymmetric Cranial Nerve Palsies. Pediatric Neurology, 2019. 92: p. 71-72.

- To survive in the harsh environment, the bacteria change into a spore form. Once inside the infant’s immature gut, the spores germinate into active bacteria, begin to multiply, and release toxins that enter the baby’s bloodstream and ultimately disrupt their nervous system.

Pathophysiology

C. botulinum produces several subtypes of botulinum toxin. Each subtype is associated with a distinct bacterial strain. The neurotoxin produced by the active form is highly potent, and it induces descending paralysis. This toxin enters the presynaptic nerve terminals and then inhibits the release of acetylcholine by blocking the calcium channels. The disruption reduces the availability of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. This reduced availability led to flaccid paralysis. In most cases, the bulbar muscles (those involved in facial expression and swallowing) are affected before the limb muscles. Older children have sufficient gastric acidity to prevent spore germination. Hence, infant botulism occurs exclusively in younger children due to their reduced gastric acidity.

Symptoms of Infant Botulism

The incubation period ranges from 3 to 30 days. The peak onset typically occurs between three and four months of age. The initial symptoms, such as diarrhoea and vomiting, show gastrointestinal involvement.

The classical clinical features of the condition include:

- Constipation (often the first and most consistent symptom)

- Choking or gagging while feeding

- Poor feeding and weak sucking reflex

- Ptosis (eyelid drooping)

- Hypotonia (floppy limbs or weak muscle tone)

- Lethargy or listlessness

- Lack of facial expressions

- Changes in bowel movement

- Irritability

- Seizures (rare)

- Weak cry

- Respiratory distress

- Hypotension (In severe cases)

- Cranial nerve abnormalities (e.g., poor eye movement)5Midura, T.F., Update: infant botulism. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1996. 9(2): p. 119-125.6Cox, N., and R. Hinkle, Infant botulism. American family physician, 2002. 65(7): p. 1388-1393.

These signs reflect the descending progression of paralysis, starting from the cranial nerves and moving downward. Early recognition and prompt treatment are essential to prevent respiratory failure and other complications.

Diagnosis of Infant Botulism

Infants can not tell their symptoms or answer questions about their feelings. Therefore, diagnosis relies heavily on caregiver observations and clinical suspicion by the healthcare provider. The physician uses a combination of clinical findings, physical examination, and diagnostic testing to confirm the diagnosis.

Physical Examination:

- Many mothers notice poor suck and ineffective feeding, often associated with breast engorgement due to reduced feeding.

- The mental status of such infants is usually preserved.

- The doctor can observe a decreased anal sphincter tone and diminished deep tendon reflexes.

- Sensation remains intact despite profound hypotonia (it might be challenging to assess due to the weak muscles).

- The key diagnostic clues can include hoarse or weak cry, poor suck, constipation, hypotonia, and symmetrical descending weakness. A few additional findings include a diminished gag reflex and significant head lag.

- Muscular fatigue can aid in diagnosis. There is a sluggish pupillary response to light (after repetitive light exposure for a few minutes in a dark room).7Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

Laboratory Tests:

A definitive diagnosis is made through toxin detection or isolation of C. botulinum from clinical specimens. These include:

Direct Toxin Essay

The examiner performs this procedure on gastric contents, serum, or stool. They collect the stool samples using an enema and store them in a sterile container without any preservatives. The assay uses techniques such as mouse bioassay and mass spectrometry to detect botulinum toxin types.

Microbiological culture or Polymerase Chain Reaction

The faecal specimen is cultured in specialized media to isolate C. botulinum. The passed stool is the most preferred specimen for culturing and investigating the toxin. In the case of a constipated child, performing colonic irrigation with limited amounts of sterile saline is necessary. The examiner collects a 25 mL effluent or 25 g stool sample in a sterile container and refrigerates it.8Midura, T.F., Update: infant botulism. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1996. 9(2): p. 119-125.

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) detects C. botulinum DNA and can confirm the presence of spores within 24–72 hours.9Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

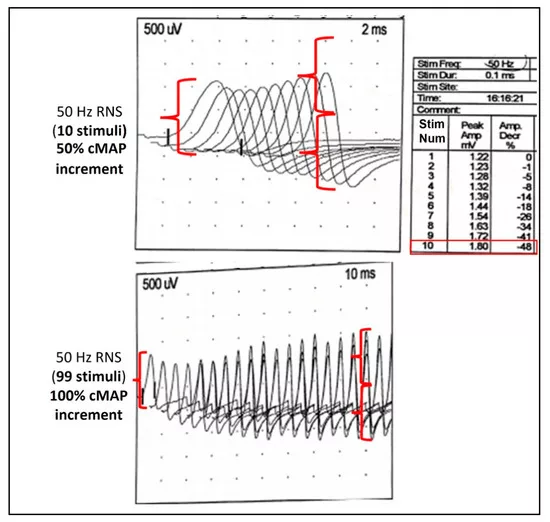

Electrodiagnostic Testing:

Researchers propose standardized electrodiagnostic testing, particularly electromyography (EMG), in infants with suspected infant botulism. EMG results can be normal in the early stages of the disease; hence, additional serial testing may be necessary.

Researchers have identified a diagnostic triad on EMG that supports the diagnosis.10Gutierrez, A.R., J. Bodensteiner, and L. Gutmann, Topical review: electrodiagnosis of infantile botulism. Journal of Child Neurology, 1994. 9(4): p. 362-366. This triad includes:

- Decreased amplitude of compound muscle action potential in at least two muscle groups. It will indicate reduced muscle response due to impaired acetylcholine release.

- Tetanic and post-tetanic facilitation in neuromuscular transmission.

- Prolonged post-tetanic facilitation lasting more than 120 seconds without post-tetanic exhaustion. This finding distinguishes botulism from other neuromuscular disorders.11Rosow, L.K. and J.B. Strober, Infant botulism: review and clinical update. Pediatric Neurology, 2015. 52(5): p. 487-492.

Treatment & Management of Infant Botulism

Infant botulism is a treatable condition. It’s better for your child if the treatment starts as soon as possible.

Immediate Actions:

Infant botulism is a medical emergency, and early recognition and immediate intervention are crucial to prevent life-threatening complications. The doctors usually do not wait for laboratory confirmation to start the therapy.

BabyBIG:

Intravenous Botulism Immune Globulin (marketed as BabyBIG) is an FDA-approved antitoxin for infants.12Arnon, S.S., Creation and development of the public service orphan drug Human Botulism Immune Globulin. Pediatrics, 2007. 119(4): p. 785-789.

It is a highly effective antitoxin that neutralizes the circulating botulinum toxin. It also prevents further nerve damage; however, it cannot reverse existing paralysis. This single-dose treatment is administered over 30 minutes. It is more effective when administered within 24 hours of symptom onset.13Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

It has the benefits of reducing the duration of hospitalization, intensive care, and mechanical ventilation. The cost of a single dose is approximately $43,000, though hospitals often access it through specialized public health programs.14Gooding, N., R. Kayani, and L. Whitehead, O5 Treatment of infantile botulism with botulism immune globulin (BabyBIG). 2019, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Antibiotics:

Antibiotics are not recommended for treating infant botulism. In particular, aminoglycosides must be avoided because they can worsen neuromuscular weakness. If there is an accompanying wound infection, metronidazole or penicillin G may be considered.

Supportive Care:

Supportive care is also essential. It is often provided in the intensive care unit.

- For respiratory support, doctors closely monitor breathing for signs of respiratory arrest and hypoventilation. If the child’s respiratory muscles are affected, he/or she may require mechanical ventilation.

- Suctioning for airway management to clear the secretion and prevent aspiration.

- Nutritional support, including tube feeding and IV fluids, is necessary in cases of impaired swallowing.

- Continuous monitoring of vital signs and for secondary infections or complications is required.

Prevention of Infant Botulism

There is no way to prevent infant botulism with certainty, as botulism-causing spores are widespread. However, the following measures can help:

- Avoid unproven home remedies for infants.

- Avoid non-pasteurised foods for infants.

- Do not feed honey or products containing honey to infants under the age of one year.

Prognosis & Differential Diagnosis

Early diagnosis and intervention with human BIG-IV can lead to a favorable prognosis. Most infants recover completely within several months to about a year. After hospitalization, a regular follow-up with the neurologist is necessary. The mortality rate for this condition is less than 1% in the United States.15Rosow LK, Strober JB. Infant botulism: review and clinical update. Pediatric Neurology. 2015 May;52(5):487-492. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.01.002.

The differential diagnosis of this condition presents overlapping features such as altered mental status, weakness, and hypotonia. The differential diagnosis of infant botulism includes:

- Congenital myopathy

- Myasthenia gravis

- Leigh disease

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Sepsis

- Inborn errors of metabolism

- Severe dehydration

Complications of Infant Botulism

The severe cases of infant botulism can lead to:

- Urinary retention due to autonomic dysfunction.

- Aspiration, apnea, and respiratory failure due to progressive neuromuscular weakness.

- These complications can lead to death without timely intervention.

Final Remarks

Infant botulism is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. The use of BIG-IV has substantially decreased mortality and hospital costs. Prompt recognition, timely intervention, and supportive care can help infants recover fully. However, parents must be advised on safe food handling practices.

Refrences

- 1Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

- 2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Infant Botulism FAQs. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/infant-botulism.html

- 3Pickett, J., & Berg, B. (1992). Infant botulism: A public health perspective. American Public Health Association.

- 4Lyons-Warren, A.M., S.R. Risen, and G. Clark, Infant Botulism With Asymmetric Cranial Nerve Palsies. Pediatric Neurology, 2019. 92: p. 71-72.

- 5Midura, T.F., Update: infant botulism. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1996. 9(2): p. 119-125.

- 6Cox, N., and R. Hinkle, Infant botulism. American family physician, 2002. 65(7): p. 1388-1393.

- 7Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

- 8Midura, T.F., Update: infant botulism. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1996. 9(2): p. 119-125.

- 9Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

- 10Gutierrez, A.R., J. Bodensteiner, and L. Gutmann, Topical review: electrodiagnosis of infantile botulism. Journal of Child Neurology, 1994. 9(4): p. 362-366.

- 11Rosow, L.K. and J.B. Strober, Infant botulism: review and clinical update. Pediatric Neurology, 2015. 52(5): p. 487-492.

- 12Arnon, S.S., Creation and development of the public service orphan drug Human Botulism Immune Globulin. Pediatrics, 2007. 119(4): p. 785-789.

- 13Ngoc L. Van Horn, M.S., Infantile Botulism. 2025.

- 14Gooding, N., R. Kayani, and L. Whitehead, O5 Treatment of infantile botulism with botulism immune globulin (BabyBIG). 2019, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

- 15Rosow LK, Strober JB. Infant botulism: review and clinical update. Pediatric Neurology. 2015 May;52(5):487-492. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.01.002.