Pyloric stenosis is a disease in infants that develops when the pylorus muscle of their stomach becomes abnormally thick. The thickness of the pylorus muscle does not allow food to proceed further for digestion, ultimately causing vomiting. Several factors contribute to the development of pyloric stenosis. Surgery is the primary and most effective treatment for this condition.

What is Pyloric Stenosis?

Pyloric stenosis, also known as hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, involves the abnormal enlargement and thickening of the pylorus muscle at the stomach’s outlet. This thickened muscle creates a blockage that prevents food from moving into the small intestine. As a result, food accumulates in the stomach and sometimes the esophagus, leading to symptoms such as projectile vomiting after feeding. Other symptoms include dehydration, weight loss, and constant hunger despite vomiting. The food starts accumulating in the stomach and the esophagus. Due to indigestion of food, infants develop symptoms of severe nausea and vomiting after every feed. They lose weight and get dehydrated. Infants with pyloric stenosis mostly feel hungry all day.

Infants with pyloric stenosis typically appear healthy at birth, as the condition generally develops between 2 to 6 weeks of age and is uncommon after 6 months.1Garfield, K., & Sergent, S. R. (2023). Pyloric Stenosis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Causes of Pyloric Stenosis

The stomach has two types of muscles: Circular and Longitudinal. Excessive thickening of both of these muscles makes the antrum of the stomach small and narrow. As a result, food cannot pass freely from the antrum to the small intestine. The stomach’s mucosa also thickens, and in severe cases, the abdomen becomes distended due to the accumulation of food in it.

The causes of this condition are multiple. Some infants develop stenosis due to environmental factors, while others have hereditary causes.

One reason is nitric oxide synthase deficiency. The deficiency leads to a lack of nitric oxide in the stomach, which acts as a non-cholinergic noradrenergic relaxant for the stomach muscles. Pyloric stenosis develops in the absence of muscle relaxation.

The use of macrolide antibiotics in infants is a significant risk factor behind pyloric stenosis. Studies show that macrolide causes this condition, usually when an infant is exposed in the first 2 weeks of life. Some cases also present a history of macrolide intake by the mother in the first two weeks after giving birth. Moreover, the risk increases in an infant if the mother has diabetes or is a smoker.

An increase in the acidity of the duodenum also contributes to the development of this condition. Due to hyperacidity in the duodenum, there is more contraction of the pylorus muscle, hence, the stenosis.

Some cases are also heritable, but they are not significant causes. Nearly 7% of children get pyloric stenosis if their parents are also affected. Another study shows that pyloric stenosis may develop due to low serum lipids in the body.2Panteli C. (2009). New insights into the pathogenesis of infantile pyloric stenosis. Pediatric Surgery International, 25(12), 1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-009-2484-x

How common is Pyloric Stenosis?

In 1000 live births annually, pyloric stenosis develops in almost 2 to 5 infants, and the ratio is higher in males than females.

Some cases are familial. Concerning race, studies have shown that this condition develops more in the white population, and fewer cases have been seen in Indian, Asian, or Black populations.3Galea, R., & Said, E. (2018). Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: An Epidemiological Review. Neonatal network: NN, 37(4), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1891/0730-0832.37.4.19

Symptoms & Signs

Infants with this condition initially present with non-bilious vomiting as the obstruction lies before the opening of the common bile duct; hence, the bile isn’t involved. In some cases, vomiting becomes projectile. Due to constant vomiting after every feed, the infant feels hungry all day and asks for more feed. When vomiting becomes severe and continues for a more extended period, it may form Mallory-Weiss tears in the esophagus, and the color of the vomiting becomes dark or coffee-colored due to the blood staining.

As vomiting persists, several secondary signs develop, including:

- Weight loss due to insufficient calorie intake.

- Lethargy from decreased energy levels.

- Dehydration is marked by dry skin, poor skin elasticity, sunken fontanelles, and overall tiredness.

During a physical examination, a physician may detect a hard, movable, olive-shaped mass in the infant’s right upper abdomen. This mass, typically 1–2 cm in diameter, represents the hypertrophied pylorus. It is best palpated when the stomach is empty, either after vomiting or following the insertion of a nasogastric tube to evacuate gastric contents.

Moreover, infants with this condition show observable signs of dehydration, such as dry skin, depressed fontanelle, poor skin turgor, and tiredness.4Shaoul, R., Enav, B., Steiner, Z., Mogilner, J., & Jaffe, M. (2004). Clinical presentation of pyloric stenosis: the change is in our hands. The Israel Medical Association journal: IMAJ, 6(3), 134–137 In some infants, visible peristaltic waves can be observed just before vomiting, as the stomach muscles attempt to push food past the obstruction.

These symptoms, particularly the combination of projectile vomiting, dehydration, and the palpable olive-shaped mass, are classic diagnostic features of pyloric stenosis.

Diagnosis of Pyloric Stenosis

Pyloric stenosis in infants is easily diagnosed by taking a history of the symptoms and looking for observable signs such as vomiting, weight loss, dehydration, dry skin, and lethargy. Proper palpation of the abdomen also reveals the presence of an olive-shaped mass, which eases the diagnosis.

In addition to history and physical examination, some other modalities that are used to diagnose are:

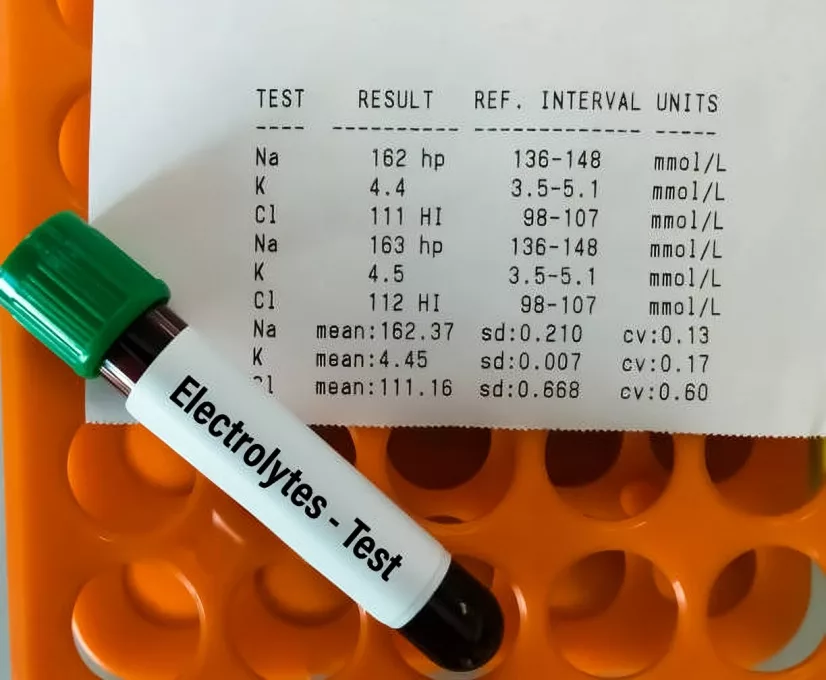

Electrolytes:

Due to severe vomiting, the infants lose most of the hydrochloric acid from their bodies. As a result, the kidney compensates for it by conserving the hydrogen ions in the body and losing the potassium at the expense of hydrogen ions. That’s why the classic laboratory findings of infants with pyloric stenosis are hypochloremic hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. Nowadays, this condition is diagnosed and treated early, which is why this finding is present in less than 50% of cases. Infants who face delayed treatment for pyloric stenosis develop an electrolyte imbalance in their bodies. Some infants also develop hypernatremia or hyponatremia and increased bilirubin due to severe dehydration. 5Touloukian, R. J., & Higgins, E. (1983). The spectrum of serum electrolytes in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Journal of pediatric surgery, 18(4), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80188-

Ultrasonography:

The choice of investigation is ultrasonography, as it is a highly specific and sensitive modality. Although this condition is easily diagnosed by the presence of a mass in the abdomen, ultrasound makes the diagnosis more confirmed. Ultrasound helps to see the thickened pyloric muscle in both transverse and longitudinal planes. The essential criteria for naming it pyloric stenosis is the thickness of the pylorus muscle of 3mm or greater and the length of the pylorus of at least 13mm. Ultrasound of pyloric stenosis also shows some other findings, such as the “antral nipple” sign, “shoulder” sign, and the “donut” sign. 6Piotto, L., Gent, R., Taranath, A., Bibbo, G., & Goh, D. W. (2022). Ultrasound diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis – Time to change the criteria. Australasian Journal of ultrasound in medicine, 25(3), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajum.12305

Barium Study:

A barium study is not usually performed these days to diagnose pyloric stenosis. However, it was an essential modality in the past as it shows the “shoulder “sign. This sign is due to the collection of barium behind the obstruction in the antrum of the stomach. Some infants also show the “double track” sign when barium is compressed inside the stomach due to the thickening of the pylorus muscle. However, as seen in many other diseases, the “double track” sign is not specific to pyloric stenosis. 7Arthur, R. J., Ziervogel, M. A., & Azmy, A. F. (1984). Barium meal examination of infants under 4 months of age presenting with vomiting. A review of 100 cases. Pediatric radiology, 14(2), 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01625813

Upper GI Endoscopy:

Endoscopy is helpful in cases where infants don’t present with the typical symptoms of pyloric stenosis, such as vomiting. Upper GI endoscopy also diagnoses complicated cases that are not easily diagnosed by ultrasound and laboratory studies.

Treatment of Pyloric Stenosis

Essential steps for treatment are:

Resuscitation:

Resuscitation is the first step in managing infants with severe pyloric stenosis. Due to vomiting, infants become too dehydrated, and there is a chance that they might get hypovolemic shock. To avoid this condition, early resuscitation with fluids is necessary. Management with fluids corrects the deficiency of fluids and electrolytes and maintains the acid-base balance in their bodies.

The primary fluid used to treat mild or moderate cases of infant dehydration is 5% dextrose in 0.45% normal saline, along with potassium replacement of at least 20mEq/l. After giving intravenous fluid, the infant should be cautiously assessed by checking the urine output and the dehydration status. The ultimate treatment for pyloric stenosis is surgery, so a pediatric surgeon should be consulted after managing the dehydration.8Dalton, B. G., Gonzalez, K. W., Boda, S. R., Thomas, P. G., Sherman, A. K., & St Peter, S. D. (2016). Optimizing fluid resuscitation in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Journal of pediatric surgery, 51(8), 1279–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.01.013

Medical Treatment:

Physicians advise medical treatment for pyloric stenosis in conditions when the surgical option is contraindicated. Nonsurgical management is oral or intravenous atropine sulfate. Although atropine sulfate has a lower success rate than surgery, it may help a little to overcome the severe symptoms.

Intravenous Atropine is given to the infant for at least 10 days in a dose of 0.04 to 0.225mg/kg/day. An oral dose of atropine is 0.08-0.45mg/kg/day for 3 weeks to 4 months.

Atropine sulfate doesn’t cause side effects in many cases, but some may show symptoms like mild facial flushing, increased heartbeat, and raised alanine transaminase in the body.9Owen, R. P., Almond, S. L., & Humphrey, G. M. (2012). Atropine sulfate: rescue therapy for pyloric stenosis. BMJ case reports 2012, bcr2012006489. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006489

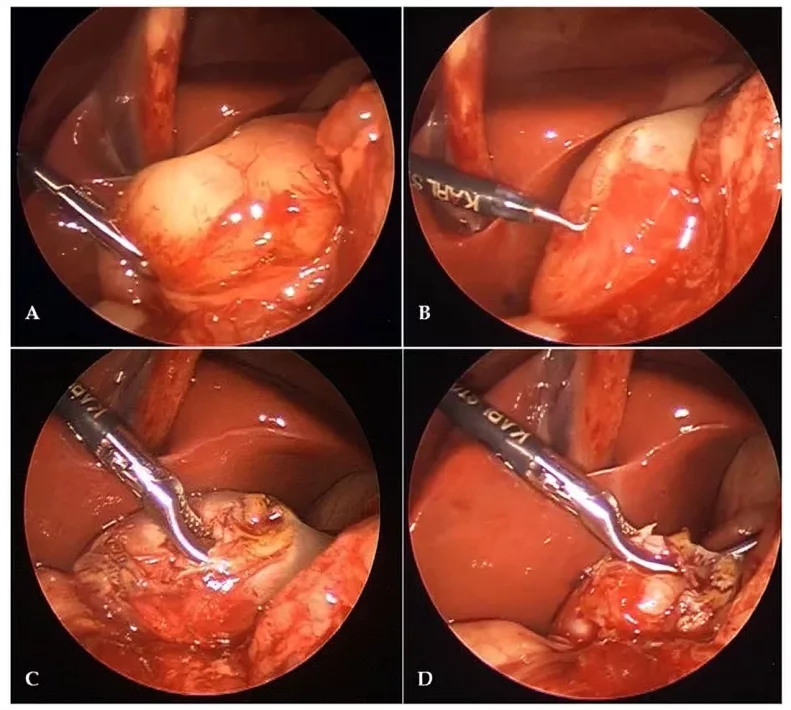

Surgical Management:

Pyloromyotomy is the surgical management of pyloric stenosis. The surgeon removes the mass at the antro-pyloric junction, which is the leading cause of obstruction in pyloric stenosis. The stomach’s mucosa remains intact in pyloromyotomy.

In the past, surgery was done by making a right upper quadrant transverse incision. Surgeons compared the pros and cons of different incisions for open and laparoscopic surgery.

Studies have proved that the laparoscopic procedure is far better than the open one as it has fewer complications, less time consumption, is less costly, and fewer hospital stays. However, some reviews still suggest a higher risk of mucosal injury in laparoscopy procedures than in open surgery.10White, J. S., Clements, W. D., Heggarty, P., Sidhu, S., Mackle, E., & Stirling, I. (2003). Treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a district general hospital: a review of 160 cases. Journal of pediatric surgery, 38(9), 1333–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00391-9

Aftercare of infants after Surgery

After pyloromyotomy, intravenous fluids should be continued as long as the infant is under the effects of anesthesia.

Continuous vomiting after surgery might cause discomfort in the patient and anxiety for his attendants. Therefore, Intravenous therapy should be given after 4-8 hours of anesthesia to avoid vomiting or regurgitation. If the patient continues to vomit even after 5 days of surgery, further investigation should be done to rule out the cause.

Furthermore, the infants should be continuously observed for surgical complications such as bleeding or infection.

Difference between Pyloric Stenosis & Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux is the backward flow of food from the stomach to the esophagus due to a faulty lower esophageal sphincter. It results in heartburn and regurgitation. On the other hand, pyloric stenosis is a thickening of the pylorus muscle, and it causes projectile vomiting. Reflux disease doesn’t result in vomiting.

Causes are various, while the closure of the sphincter causes reflux disease.

Risk factors of pyloric stenosis are many, including antibiotic use, smoking in pregnancy, and genetics, while risk factors of reflux disease are obesity, pregnancy, and smoking.

Long-term cases of gastroesophageal reflux disease can cause esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. However, severe pyloric stenosis causes shock and dehydration.

Surgery is the most effective management for pyloric stenosis and reflux disease, while lifestyle modifications and medicines like antacids or H2 blockers can treat reflux disease.11Smith, G. A., Mihalov, L., & Shields, B. J. (1999). Diagnostic aids in the differentiation of pyloric stenosis from severe gastroesophageal reflux during early infancy: the utility of serum bicarbonate and serum chloride. The American journal of emergency medicine, 17(1), 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90009-8

Complications of Pyloric Stenosis

Most of the complications are due to severe vomiting, such as electrolyte imbalance, tears in the walls of the esophagus, weight loss, lethargy, stomach irritation, and dehydration. Prolonged cases lead to stunted growth and development of the infant and can also affect brain growth and maturation. Some complications also arise after the surgical procedure ( pyloromyotomy ), like infection, bleeding from the scar, incomplete removal of the mass from the stomach, and mucosal perforation.12Kelay, A., & Hall, N. J. (2018). Perioperative Complications of Surgery for Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Official Journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery … [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie, 28(2), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1637016

Prognosis of Pyloric Stenosis

The prognosis is good as it is completely cured by surgery if diagnosed and treated in the early stages. Death due to this condition is infrequent. The delayed cases might develop hypovolemic shock and severe dehydration.13Muse, A. I., Hussein, B. O., Adem, B. M., Osman, M. O., Abdulahi, Z. B., & Ibrahim, M. A. (2024). Treatment outcome and associated factors of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis at eastern Ethiopia public hospitals. BMC surgery, 24(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02567-

Conclusion

In short, this condition develops due to the thickening of the pylorus muscle. Due to the thickening, food cannot pass quickly to the intestine, leading to projectile vomiting and dehydration. Infants feel a constant hunger due to continuous vomiting, and eventually, they lose weight. Causes are multifactorial, including long-term antibiotic use. Surgery is the only definite management for pyloric stenosis. The success rate is higher if surgery is done in the earlier stage of the disease.

Refrences

- 1Garfield, K., & Sergent, S. R. (2023). Pyloric Stenosis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- 2Panteli C. (2009). New insights into the pathogenesis of infantile pyloric stenosis. Pediatric Surgery International, 25(12), 1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-009-2484-x

- 3Galea, R., & Said, E. (2018). Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: An Epidemiological Review. Neonatal network: NN, 37(4), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1891/0730-0832.37.4.19

- 4Shaoul, R., Enav, B., Steiner, Z., Mogilner, J., & Jaffe, M. (2004). Clinical presentation of pyloric stenosis: the change is in our hands. The Israel Medical Association journal: IMAJ, 6(3), 134–137

- 5Touloukian, R. J., & Higgins, E. (1983). The spectrum of serum electrolytes in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Journal of pediatric surgery, 18(4), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80188-

- 6Piotto, L., Gent, R., Taranath, A., Bibbo, G., & Goh, D. W. (2022). Ultrasound diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis – Time to change the criteria. Australasian Journal of ultrasound in medicine, 25(3), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajum.12305

- 7Arthur, R. J., Ziervogel, M. A., & Azmy, A. F. (1984). Barium meal examination of infants under 4 months of age presenting with vomiting. A review of 100 cases. Pediatric radiology, 14(2), 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01625813

- 8Dalton, B. G., Gonzalez, K. W., Boda, S. R., Thomas, P. G., Sherman, A. K., & St Peter, S. D. (2016). Optimizing fluid resuscitation in hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Journal of pediatric surgery, 51(8), 1279–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.01.013

- 9Owen, R. P., Almond, S. L., & Humphrey, G. M. (2012). Atropine sulfate: rescue therapy for pyloric stenosis. BMJ case reports 2012, bcr2012006489. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006489

- 10White, J. S., Clements, W. D., Heggarty, P., Sidhu, S., Mackle, E., & Stirling, I. (2003). Treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a district general hospital: a review of 160 cases. Journal of pediatric surgery, 38(9), 1333–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00391-9

- 11Smith, G. A., Mihalov, L., & Shields, B. J. (1999). Diagnostic aids in the differentiation of pyloric stenosis from severe gastroesophageal reflux during early infancy: the utility of serum bicarbonate and serum chloride. The American journal of emergency medicine, 17(1), 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90009-8

- 12Kelay, A., & Hall, N. J. (2018). Perioperative Complications of Surgery for Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Official Journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery … [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie, 28(2), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1637016

- 13Muse, A. I., Hussein, B. O., Adem, B. M., Osman, M. O., Abdulahi, Z. B., & Ibrahim, M. A. (2024). Treatment outcome and associated factors of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis at eastern Ethiopia public hospitals. BMC surgery, 24(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02567-