Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a parasitic disease caused by blood flukes from the Schistosoma genus. These parasites develop in freshwater snails and release cercariae (larvae). When your skin comes in contact with the contaminated water, these parasites can move into your body and can live there for years. Once inside the body, the parasites migrate to blood vessels, primarily affecting the bladder, intestines, and liver. Chronic infection can lead to severe complications such as liver fibrosis, portal hypertension, and bladder cancer. The three primary species of schistosomes that can affect humans are S. japonicum, S. haematobium, and S. mansoni.1Gryseels, B., Polman, K., Clerinx, J., & Kestens, L. (2006). Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet, 368(9541), 1106-1118.

It is an endemic disease in several countries in tropical and subtropical areas.2Colley, D. G., Bustinduy, A. L., Secor, W. E., & King, C. H. (2014). Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet, 383(9936), 2253-2264. However, It can also occur in non-endemic areas. The disease is among the most prevalent and predominant human parasitic contagions. The estimated population affected worldwide by schistosomiasis is 230 to 250 million annually. Every year, this disease can cause 280,000 deaths, and around 779 million humans are at risk.3Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

What are Schistosomes?

Schistosomes are small, cylindrical parasitic worms, typically 7–20 mm long, with a greyish or white appearance. They have a complex tegument that protects them from the host’s immune defenses and aids nutrient absorption. These worms possess well-developed reproductive organs, a blind digestive tract, and two terminal suckers—an oral sucker for feeding and a ventral sucker for attachment to host tissues.

Types of Schistosomiasis

There are three main types of Schistosomiasis:

Urinary or Vesical Schistosomiasis:

S. haematobium causes this condition. This form targets the venous plexus of the bladder and urogenital organs. In its severe form, it can cause the following complications:

- Female infertility

- Spontaneous abortions

- Sexually transmitted disorders

- Obstruction in the urinary tract

- Chronic kidney disorders

- Renal failure

It is endemic in the countries of the Middle East and Africa.4Lackey, E. K., & Horrall, S. Continuing Education Activity.

Intestinal or Manson’s Schistosomiasis

S. mansoni causes this disease. It is endemic to the Caribbean, Northern South America, Africa, and the Middle East. It can lead to the following complications:

- Abdominal pain and diarrhea

- Blood in stool (hematochezia)

- Liver enlargement

- Portal hypertension5Lambertucci, J. R. (2010). Acute schistosomiasis mansoni: revisited and reconsidered. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 105, 422-435.

Eastern or Japonica Schistosomiasis

S. japonicum causes this chronic type of schistosomiasis. It is most common in southern China, Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand. In its most severe forms, it is characterized by:

- Ascites (abdominal fluid accumulation)

- Portal hypertension

- Liver fibrosis

- Oesophageal varices

It can also lead to death.6Ohta, N. (2004). Centenary symposium to celebrate the discovery of Schistosoma japonicum, Part 2. 31 March, 2003. Kurume, Japan.

Pathophysiology or Life Cycle of Schistosome

The life cycle of Schistosoma occurs in two hosts: the snails and mammals. Asexual reproduction occurs in snails, and sexual reproduction occurs in mammals. The schistosome eggs are discharged with urine or feces, depending on the species. These eggs hatch and release miracidia under suitable conditions. Miracidia swim and enter specific snail intermediate hosts. The stages of flatworm in the snail include:

- Generations of sporocysts

- Sporocysts multiply and grow into cercariae.

The mammalian hosts of schistosomes include humans, dogs, and mice. These parasites grow, mature, and lay eggs in their mammalian hosts. Snails can shed hundreds of cercariae daily. After being eliminated from the snail, these infective cercariae swim and infect the human host.

After penetration, the cercariae shed forked tails and develop into schistosomulae. The schistosomulae travel through the venous circulation and reach the lungs. From the lungs, they migrate into the heart, stay in the liver, and develop there. When they are mature, schistosomula depart from the liver via the portal vein system. Female and male worms reside and copulate in the mesenteric venules. The locations of the adult worms vary by species. S. mansoni occurs in the inferior mesenteric veins (dispiriting the large intestine). The S. japonicum is usually found in the superior mesenteric veins (draining the small intestine). The S. haematobium inhabits the vesicular and pelvic venous plexes of the bladder. The species’ eggs move progressively and are eliminated in the water, and the life cycle begins again.7Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

Causes of the Infection & Transmission

Schistosomiasis transmission occurs when people come into contact with freshwater contaminated by schistosome larvae, typically during agricultural, domestic, or recreational activities. The parasite, which develops in freshwater snails, can penetrate human skin but cannot be transmitted directly from person to person, as schistosomiasis requires the environmental lifecycle in snails to infect new hosts. Irrigation and Dam projects are the potential sites for schistosomiasis outbreaks. Moreover, seasonal migration of employees and movement of the infected population can cause the spread of schistosomiasis.8Mohamed, I., Kinung’hi, S., Mwinzi, P. N., Onkanga, I. O., Andiego, K., Muchiri, G., … & Olsen, A. (2018). Diet and hygiene practices influence morbidity in schoolchildren living in Schistosomiasis endemic areas along Lake Victoria in Kenya and Tanzania—A cross-sectional study. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 12(3), e0006373.

Signs & Symptoms of Schistosomiasis

Initial signs and symptoms include a rash or itchiness. Later symptoms of acute schistosomiasis (those that develop within 14 to 84 days) include:

- Headache

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Rash

- Myalgia

- Cough

- Respiratory symptoms.9Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

Intestinal schistosomiasis can cause:

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Blood in the stool (hematochezia)

- Liver enlargement (hepatomegaly)

- Enlargement of spleen

The signs of urogenital schistosomiasis are:

- Hematuria (blood in the urine)

- Damage to the kidneys

- Bladder cancer

- Dysuria

In females, this disease can cause:

- Genital lesions

- Vaginal pain

- Bleeding

- Miscarriage

- Ectopic pregnancies10Laxman, V. V., Adamson, B., & Mahmood, T. (2008). Recurrent ectopic pregnancy due to Schistosoma hematobium. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28(4), 461-462.

In chronic schistosomiasis, the symptoms include:

- Liver fibrosis

- Bladder cancer

- Seizures

- Paralysis

- Portal Hypertension11Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

Diagnosing schistosomiasis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, epidemiological history, and laboratory tests.

Clinical Evaluation & Epidemiological History

The healthcare provider will first look for clinical signs. Exposure history is also essential. The provider will ask questions about travel to endemic areas, involvement in freshwater activities, and history of swimming or bathing in contaminated areas.

Laboratory Tests

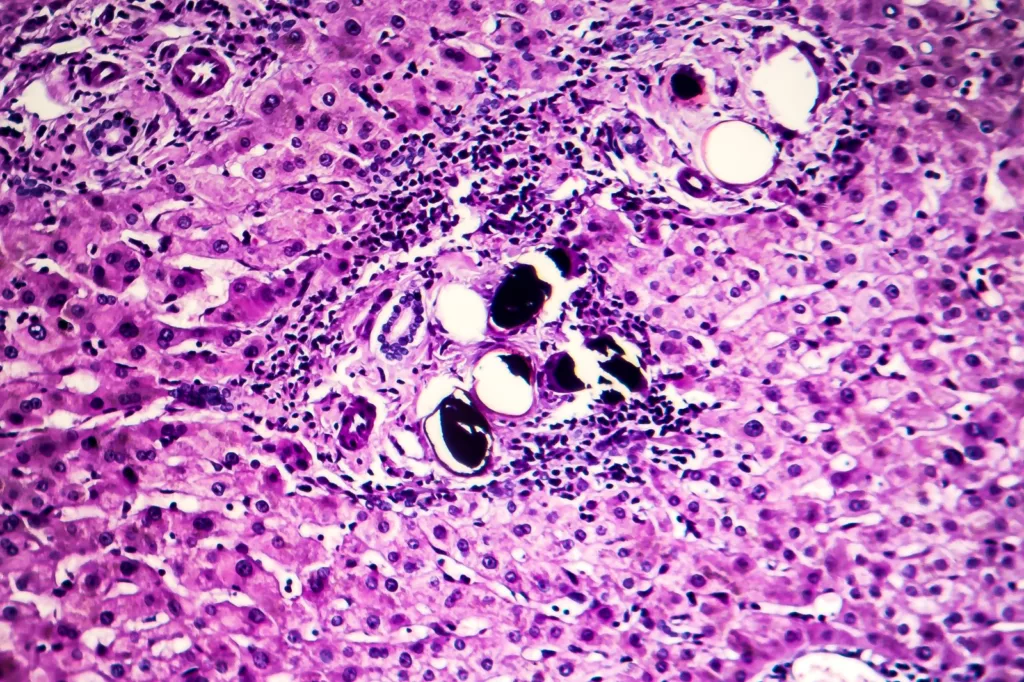

Microscopic Examination:

The most common diagnostic method involves examining stool or urine for eggs under a microscope. Microscopic egg counts help determine the load of infection.

Miracidia Hatching Test (MHT)

The collected samples are placed in a suitable environment that can stimulate hatching. After the incubation period, the investigator examines the sample microscopically to observe the miracida.

Kato-Katz Stool Examination

This test requires a light microscope and three slides. The stool sample is transferred to the microscopic slide, which is then covered with cellophane soaked in glycerine. The investigator examines the sample for eggs. In this test, eggs per gram of stool can be counted.

Formal Ether Concentration Technique (FECT)

The FECT stool sample test uses a centrifugal apparatus. This technique concentrates the eggs, making them easier to detect under the microscope. The stool sample and the additives are placed in a gauze in the funnel and centrifuged at 1000 g for about 3 minutes. Then, the investigator covers the supernatant with the help of a glass cover. The sediment for eggs is examined under the microscope.12Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

Serological Examination

Blood tests can detect antigens and antibodies related to the infection. Elevated eosinophilia indicates acute schistosomiasis. Elevated liver and renal function tests are an indication of chronic schistosomiasis. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test can identify the exposure. However, it can not differentiate between active and inactive infection.13Nour, N. M. (2010). Schistosomiasis: health effects on women. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 3(1), 28.

Molecular Examination

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a highly specific and sensitive method for detecting schistosome eggs, making it particularly useful in low-intensity infections where other diagnostic methods may fall short.14He, P., Gordon, C. A., Williams, G. M., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Hu, J., … & McManus, D. P. (2018). Real-time PCR diagnosis of Schistosoma japonicum in low transmission areas of China. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 7(01), 25-35.

Treatment of Schistosomiasis

Treatment attempts are made by controlling the infection through chemotherapy. Anthelmintics are the most commonly recommended treatment for schistosomiasis.

Medication For Schistosomiasis

Praziquantel is the most cost-effective medicine for treating this infection. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a single dose of 40 mg/kg to persons of every age. The drug is in pill form, and you can take it with food or water. Praziquantel, in this dosage, can effectively kill adult worms. It also prevents the release of eggs. However, it does not kill immature worms present in the body. So, to increase its effectiveness, this treatment needs to be repeated every two to four weeks.15Zwang, J., & Olliaro, P. L. (2014). Clinical efficacy and tolerability of praziquantel for intestinal and urinary schistosomiasis—a meta-analysis of comparative and non-comparative clinical trials. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(11), e3286.

You may have side effects from the medication or the infection itself. These might include headache, stomach pain, nausea, fever, itching, or malaise. Contact your provider about any other symptoms that seem to be getting worse. Also, consult a healthcare provider before taking any medication for this condition.

Management & Prevention of Schistosomiasis

People with severe symptoms require additional management techniques.

- Follow-up after the treatment is essential to ensure the clearance of the infection and to monitor any additional complications resulting from the treatment.

- Integration of schistosomiasis control with other health interventions can also be beneficial.

- Research into the development of a vaccine for schistosomiasis is ongoing. It would provide long-term protection from infection.

- Snail management is also helpful. Controlling the population of snails that host the schistosomiasis parasite can help reduce the spread of the disease. This control is often done using chemicals called molluscicides, which kill snails. However, because these chemicals can also harm other organisms and disrupt ecosystems, this approach is challenging to manage effectively without causing environmental harm.

Some other management options include:

- Improvement of water sanitary system

- Making positive behavioral and social changes regarding hygiene.

The preventive measures can be the following:

Environmental Management

Building and maintaining safe and clean latrines can reduce human contact with contaminated water. Every person should have access to sanitation facilities and clean water to minimize the risk of infection. Improve water management strategies to reduce the population of intermediate hosts.

Community Awareness

- Spread awareness about the importance of avoiding interaction with contaminated water.

- Promote using safe water sources.

- Avoid swimming or washing in potentially infected water.

- Use of restrooms instead of open defecation.

- Educate communities about schistosomiasis, its lifecycle, and transmission routes.

Screening & Preventive Treatment

- Conducting regular screening in endemic areas. It will help identify people with active infection.

- Treatment with praziquantel in high-risk areas, especially school-aged children, can avoid the prevalence of the ailment.

Final Remarks

Schistosomiasis is a significant health concern, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. For effective control and management, it is essential to understand its pathology, epidemiology, and preventive strategies. Immediately rush to your healthcare provider if you suspect the infection. Moreover, continued public health research efforts are crucial to combat this neglected disease.

Refrences

- 1Gryseels, B., Polman, K., Clerinx, J., & Kestens, L. (2006). Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet, 368(9541), 1106-1118.

- 2Colley, D. G., Bustinduy, A. L., Secor, W. E., & King, C. H. (2014). Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet, 383(9936), 2253-2264.

- 3Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

- 4Lackey, E. K., & Horrall, S. Continuing Education Activity.

- 5Lambertucci, J. R. (2010). Acute schistosomiasis mansoni: revisited and reconsidered. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 105, 422-435.

- 6Ohta, N. (2004). Centenary symposium to celebrate the discovery of Schistosoma japonicum, Part 2. 31 March, 2003. Kurume, Japan.

- 7Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

- 8Mohamed, I., Kinung’hi, S., Mwinzi, P. N., Onkanga, I. O., Andiego, K., Muchiri, G., … & Olsen, A. (2018). Diet and hygiene practices influence morbidity in schoolchildren living in Schistosomiasis endemic areas along Lake Victoria in Kenya and Tanzania—A cross-sectional study. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 12(3), e0006373.

- 9Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

- 10Laxman, V. V., Adamson, B., & Mahmood, T. (2008). Recurrent ectopic pregnancy due to Schistosoma hematobium. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28(4), 461-462.

- 11Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

- 12Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: life cycle, diagnosis, and control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5-9.

- 13Nour, N. M. (2010). Schistosomiasis: health effects on women. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 3(1), 28.

- 14He, P., Gordon, C. A., Williams, G. M., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Hu, J., … & McManus, D. P. (2018). Real-time PCR diagnosis of Schistosoma japonicum in low transmission areas of China. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 7(01), 25-35.

- 15Zwang, J., & Olliaro, P. L. (2014). Clinical efficacy and tolerability of praziquantel for intestinal and urinary schistosomiasis—a meta-analysis of comparative and non-comparative clinical trials. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(11), e3286.