Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a rare genetic condition where white blood cells, known as phagocytes, cannot effectively destroy certain bacteria and fungi. This makes individuals with CGD prone to recurrent, severe, and sometimes life-threatening infections.

What is Chronic Granulomatous Disease?

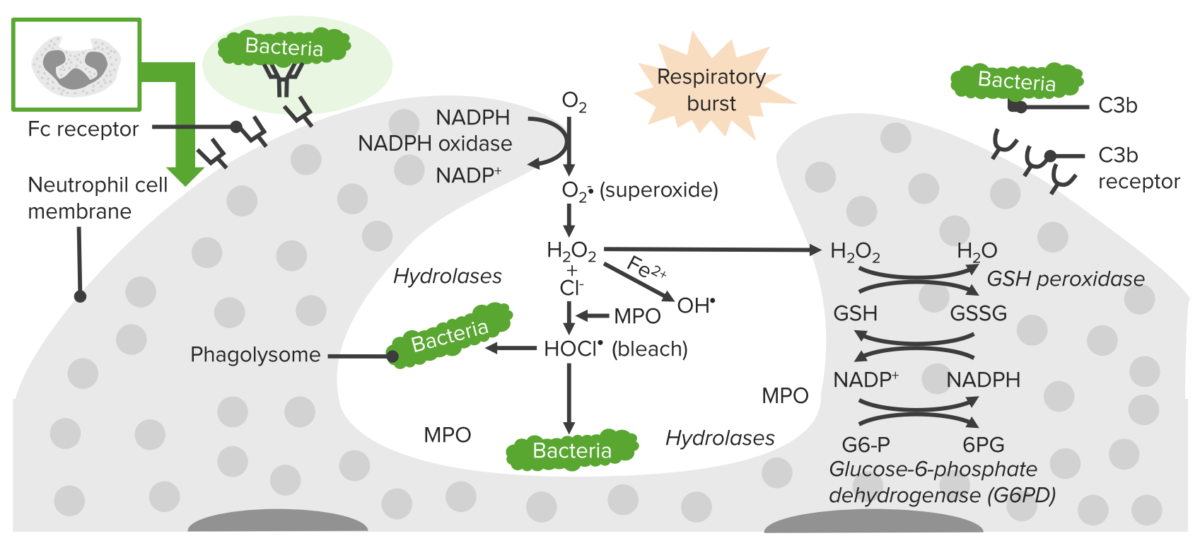

CGD is a rare, inherited primary immunodeficiency disorder caused by mutations in one of the five genes that encode components of the NADPH oxidase complex. This complex is crucial for generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) during a process called the respiratory burst, which enables phagocytic white blood cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, to kill certain bacteria and fungi. In individuals with CGD, mutations disrupt this process, leaving phagocytes unable to eliminate catalase-positive pathogens effectively.

As a result, people with CGD are highly susceptible to recurrent and severe bacterial and fungal infections, such as those caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Aspergillus species, and Burkholderia cepacia. They may also develop chronic inflammatory complications, including CGD colitis, due to dysregulated immune responses. However, the introduction of azole antifungals and the deployment of standard antibiotic prophylaxis have significantly increased overall survival.1 Yu, H. H., Yang, Y. H., & Chiang, B. L. (2021). Chronic Granulomatous Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 61(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08800-x

Causes of Chronic Granulomatous Disease

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is caused by mutations in the CYBA, CYBB, NCF1, NCF2, or NCF4 genes, which encode proteins that are essential components of the NADPH oxidase enzyme complex.2Leiding, J. W., & Holland, S. M. (2020). Chronic granulomatous disease. Stiehm’s Immune Deficiencies, 829-847.

This enzyme is critical for the immune system’s phagocytes, which use it to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide, to kill invading bacteria and fungi. These ROS are toxic to pathogens and play a crucial role in preventing infections. In addition, NADPH oxidase helps regulate the functioning of immune cells, ensuring a balanced immune response.

Mutations associated with CGD render the NADPH oxidase complex inactive or dysfunctional, leading to the production of defective or absent protein components. This impairs the phagocytes’ ability to eliminate pathogens and control inflammation, making individuals with CGD more vulnerable to recurrent infections and severe inflammatory complications.

In some cases, the genetic cause of CGD remains unknown, suggesting the possibility of mutations in other yet-to-be-identified genes.

Symptoms of CGD

Various bacteria and fungi, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Serratia marcescens, Burkholderia cepacia, Nocardia species, and Aspergillus species, can potentially trigger infections in individuals with CGD. These infections typically manifest in various body parts, including the lungs, skin, lymph nodes, liver, and intestines, among others. In individuals with chronic granulomatous diseases, these infections can result in the formation of granulomas, which are lumps filled with phagocytic cells. These granulomas have the potential to block the colon or urinary system and can lead to the development of abscesses, or boils, in areas like the lungs, liver, spleen, bones, or skin. Granulomas can sometimes even progress to a condition resembling inflammatory bowel disease, akin to Crohn’s disease.

Depending on which gene is faulty, CGD patients may also experience diabetes, autoimmune illness, cardiac or renal issues, or both. However, to determine whether phagocytes are working normally and producing hydrogen peroxide, particular blood tests are used to diagnose CGD. It’s also common for people with CGD to experience skin, liver, stomach and intestines, brain, and eye infections.3Mortaz, E., Azempour, E., Mansouri, D., Tabarsi, P., Ghazi, M., Koenderman, L., … & Adcock, I. M. (2019). Common infections and target organs associated with chronic granulomatous disease in Iran. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology, 179(1), 62-73 Symptoms associated with infections include:

- Fever.

- Pleuric Chest pain.

- Swollen and sore lymph nodes.

- An ongoing runny nose.

- Skin irritation may include a rash, swelling, or redness.

- Mouth ulcers.

Moreover, gastrointestinal problems may include:

- Vomiting.

- Diarrhea.

- Epigastric pain.

- Bloody stool.

- A painful pocket of pus near the anus.

How is Chronic Granulomatous Disease Diagnosed?

Diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) involves a comprehensive clinical evaluation, which includes a detailed patient history assessment. To diagnose CGD, your doctor may request several tests, including:

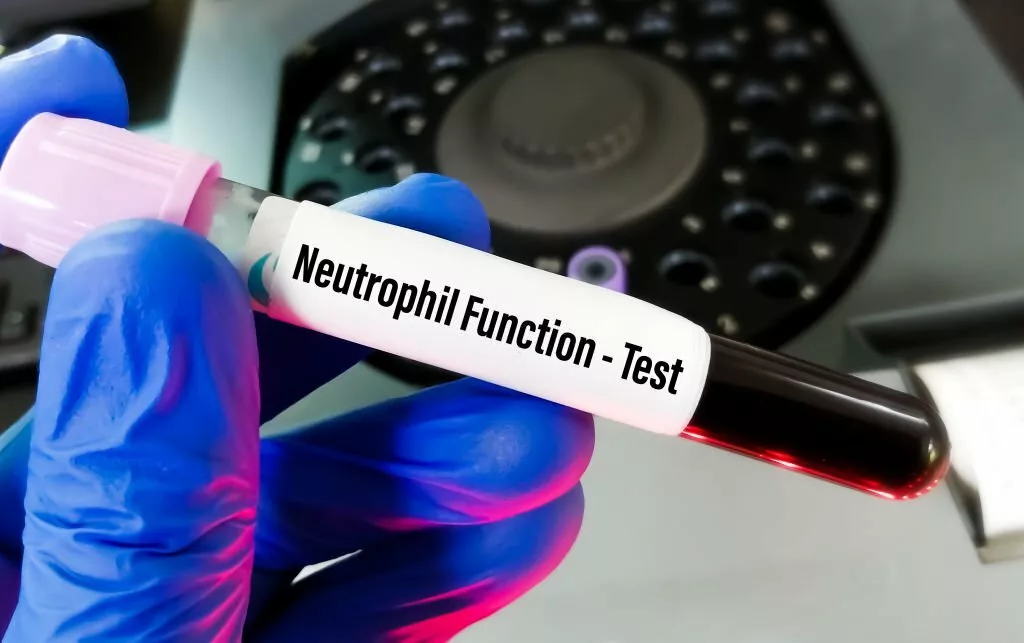

Neutrophil Function Tests

To determine how efficiently a particular kind of white blood cell known as a neutrophil is working, your doctor may do a dihydro rhodamine 123 (DHR) test or other tests. Physicians typically use this test to identify CGD.4Roos, D., & Boer, M. (2014). Molecular diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 175(2), 139-149

NBT Slide Test

Another diagnostic tool is the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) slide test, where NBT is combined with white blood cells, and their activation should induce a reaction, turning NBT into a deep blue color. Failure of this reaction suggests inadequate oxidant production by the white blood cells.

Genetic testing

To establish the existence of a particular genetic change that causes chronic granulomatous disease, your doctor might ask for a genetic test.5Gao, L. W., Yin, Q. Q., Tong, Y. J., Gui, J. G., Liu, X. Y., Feng, X. L., … & Jiang, Z. F. (2019). Clinical and genetic characteristics of Chinese pediatric patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 30(3), 378-386

Prenatal Testing

If one of your children has already been diagnosed with CGD, medical professionals might use prenatal testing to diagnose.

Treatment

The goal of CGD treatment is to manage your illness and prevent infections. Treatments could include:

Infection Management

The doctor will take steps to prevent bacterial and fungal infections before they take hold. He may use Itraconazole or a combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole as a form of treatment. If an infection develops, further antibiotics or antifungal medications may be required.6Gennery, A. R. (2021). Progress in treating chronic granulomatous disease. British Journal of Haematology, 192(2), 251-264

Interferon-Gamma

Interferon-gamma injections may occasionally be administered to you, potentially boosting immune system cells that can help you fight infections.7Lugo Reyes, S. O., González Garay, A., González Bobadilla, N. Y., Rivera Lizárraga, D. A., Madrigal Paz, A. C., Medina-Torres, E. A., … & Murata, C. (2023). Efficacy and safety of interferon-gamma in chronic granulomatous disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 43(3), 578-584

Stem Cell Transplantation

A stem cell transplant may cure CGD in some circumstances. Moreover, prognosis, donor availability, and personal preference are a few variables influencing whether stem cell transplantation is chosen as a kind of treatment.8Dedieu, C., Albert, M. H., Mahlaoui, N., Hauck, F., Hedrich, C., Baumann, U., … & Kühl, J. S. (2021). Outcome of chronic granulomatous disease‐Conventional treatment vs stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 32(3), 576-585

Pattern of Inheritance

When CYBB gene mutations cause chronic granulomatous disease, the illness is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. One of the two sex chromosomes, the X chromosome, contains the CYBB gene. One mutated copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to induce the disease in males (who have only one X chromosome). A mutation would need to occur in both copies of the gene in females (who have two X chromosomes) for it to result in the condition.9Kohn, D. B., Booth, C., Kang, E. M., Pai, S. Y., Shaw, K. L., Santilli, G., Armant, M., Buckland, K. F., Choi, U., De Ravin, S. S., Dorsey, M. J., Kuo, C. Y., Leon-Rico, D., Rivat, C., Izotova, N., Gilmour, K., Snell, K., Dip, J. X., Darwish, J., Morris, E. C., … Net4CGD

Males have X-linked recessive illnesses significantly more commonly than females since it is improbable that females will have two mutated copies of this gene. Fathers cannot pass on X-linked qualities to their sons, a trait of X-linked inheritance. Rarely females with one mutated copy of the CYBB gene experience minor signs of chronic granulomatous illness, like an increased propensity for bacterial or fungal infections.

Chronic granulomatous disease occurs when CYBA, NCF1, NCF2, or NCF4 gene mutations lead to an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, where each cell possesses both copies of the affected gene. Each parent of a person with an autosomal recessive disorder carries one copy of the defective gene, although usually, neither parent exhibits the disease’s signs and symptoms. Autosomal recessive diseases affect both males and women equally.

Life Expectancy

Prior to the broad utilization of prophylactic antimicrobial drugs, CGD earned the moniker “fatal granulomatous disease of childhood” due to patients rarely surviving beyond their initial decade. Nowadays, patients live for at least 40 years on average. Respiratory fungal infections are the main killer of CGD patients. The immune system’s functionality correlates with the degree of malfunction in the NOX enzyme, influencing an individual’s survival span.

In summary, Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency disorder resulting from genetic mutations affecting the NADPH oxidase complex. This impairs the immune system’s ability to combat certain infections. CGD can lead to various symptoms and complications, but advances in treatment have significantly improved life expectancy, with an average survival beyond 40 years. The disease’s inheritance pattern varies based on the affected gene, either X-linked recessive or autosomal recessive. Early diagnosis and effective management are key to improving the quality of life for individuals with CGD.

Refrences

- 1Yu, H. H., Yang, Y. H., & Chiang, B. L. (2021). Chronic Granulomatous Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 61(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08800-x

- 2Leiding, J. W., & Holland, S. M. (2020). Chronic granulomatous disease. Stiehm’s Immune Deficiencies, 829-847.

- 3Mortaz, E., Azempour, E., Mansouri, D., Tabarsi, P., Ghazi, M., Koenderman, L., … & Adcock, I. M. (2019). Common infections and target organs associated with chronic granulomatous disease in Iran. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology, 179(1), 62-73

- 4Roos, D., & Boer, M. (2014). Molecular diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 175(2), 139-149

- 5Gao, L. W., Yin, Q. Q., Tong, Y. J., Gui, J. G., Liu, X. Y., Feng, X. L., … & Jiang, Z. F. (2019). Clinical and genetic characteristics of Chinese pediatric patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 30(3), 378-386

- 6Gennery, A. R. (2021). Progress in treating chronic granulomatous disease. British Journal of Haematology, 192(2), 251-264

- 7Lugo Reyes, S. O., González Garay, A., González Bobadilla, N. Y., Rivera Lizárraga, D. A., Madrigal Paz, A. C., Medina-Torres, E. A., … & Murata, C. (2023). Efficacy and safety of interferon-gamma in chronic granulomatous disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 43(3), 578-584

- 8Dedieu, C., Albert, M. H., Mahlaoui, N., Hauck, F., Hedrich, C., Baumann, U., … & Kühl, J. S. (2021). Outcome of chronic granulomatous disease‐Conventional treatment vs stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 32(3), 576-585

- 9Kohn, D. B., Booth, C., Kang, E. M., Pai, S. Y., Shaw, K. L., Santilli, G., Armant, M., Buckland, K. F., Choi, U., De Ravin, S. S., Dorsey, M. J., Kuo, C. Y., Leon-Rico, D., Rivat, C., Izotova, N., Gilmour, K., Snell, K., Dip, J. X., Darwish, J., Morris, E. C., … Net4CGD