Sideroblastic Anemia (SA) is a blood disease characterized by defective iron incorporation into heme during erythropoiesis, leading to iron accumulation in the mitochondria of developing red blood cells. There are different forms of SA, all defined by the presence of ring sideroblasts (erythroblasts with perinuclear iron-engorged mitochondria) in the bone marrow.

The condition can be hereditary or acquired, depending on specific genetic mutations and their effect on heme biosynthesis, mitochondrial function, or iron-sulfur cluster formation. Unlike iron deficiency anemia, this anemia is associated with normal to elevated iron levels.1Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024. The researchers codified this condition as a class of anemia in 1960, although they first recognized it in the 1940s. It is a rare disease. It can affect many people, from infants to middle-aged and older people. Due to low incidence and prevalence, no statistical data on its epidemiology exists.2Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

Etiology of Sideroblastic Anemia

People may be born with sideroblastic anemia, which is called congenital anemia. They can also develop SA when they get exposed to certain medications, minerals, and metals or have a related condition (acquired SA).

Congenital Sideroblastic Anemia:

Congenital SA occurs as a result of some kinds of genetic abnormalities. The genetic abnormalities affect the synthesis of heme, mitochondrial synthesis, and iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis. There are three types of congenital SA. Most congenital SA cases are microcytic, but some specific mutations can also lead to normocytic or macrocytic anemia in rare cases.

Types of Congenital SA:

There are three types of congenital SA. These are:

X-Linked SA

X-linked SA, caused by mutations in the ALAS2 gene, is the most common hereditary form of SA. This condition results in mature red blood cells that are smaller than normal and appear pale, leading to iron accumulation in the body. A defect in ALAS2 impairs ALA formation, resulting in heme deficiency.3Furuyama, K. and K. Kaneko, Iron metabolism in erythroid cells and patients with congenital sideroblastic anemia. International Journal of Hematology, 2018. 107: p. 44-54.

Autosomal Recessive SA (ARCSA)

It is common among infants and young children. ARCSA happens when excessive iron accumulates in the blood. It is a serious and life-threatening disorder and is the second most common form of SA.

Mitochondrial-Linked SA

Some cases of SA result from mitochondrial mutations, including mutations in the MT-ATP6 gene. These mutations affect mitochondrial function, disrupting heme synthesis and leading to anemia. However, this form is much rarer than X-linked SA.4. Ducamp S, Fleming MD: The molecular genetics of sideroblastic anemia. Blood 133:59–69, 2019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-08-815951

Acquired Sideroblastic Anemia:

Acquired SA can arise from both primary and secondary causes.

Primary Causes

The primary causes include:

- Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): MDS is a group of blood cancers affecting the bone marrow’s normal blood cell production.

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN): MPN is a group of rare blood cancers that cause the bone marrow to produce too many blood cells.

Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS), now classified as MDS with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS), is the most common form of acquired SA. In MDS-RS, 15% or more of erythroid precursors in the bone marrow are ring sideroblasts. The cases of MDS-RS evolve in one of two ways:

- Category 1: They remain low-risk MDS with an expected lifespan.

- Category 2: They progress to high-grade MDS.

The majority of MDS-RS cases fall into the first category, while the second category includes only seven to ten percent of patients.5Patnaik, M.M. and A. Tefferi, Refractory Anemia with Ring Sideroblasts (RARS) and RARS with Thrombocytosis (RARS-T)–“2019 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-stratification, and Management”. American journal of hematology, 2019. 94(4): p. 475.

Secondary Causes

Secondary SA refers to SAs that may develop due to the following reasons:

- Excessive use of alcohol is the most common cause of acquired SA. Anemia in patients with excessive alcohol consumption is multifactorial.

- Zinc toxicity is another important cause. Zinc affects how your body uses iron and absorbs copper. Overdose of supplements, including zinc, can lead to zinc toxicity.

- Arsenic poisoning and lead poisoning can also cause the disease.

- Copper helps in creating an enzyme that protects against iron overload. The deficiency of copper can lead to defective enzyme function, which can lead to SA.

- Vitamin B helps in developing hemoglobin and helps carry oxygen; a deficiency of this vitamin can lead to SA.

- Certain medications can also lead to SA. These drugs include:

1. Chloramphenicol

2. Isoniazid

3. linezolid - Other drugs include:

1. Pyrazinamide

2. Cycloserine

3. Penicillamine

4. Melphalan

5. Fusidic acid

6. Triethylenetetramine dihydrochloride

7. Busulfan6Rodriguez-Sevilla, J.J., X. Calvo, and L. Arenillas, Causes and pathophysiology of acquired sideroblastic anemia. Genes, 2022. 13(9): p. 1562.

Secondary-acquired SA can be reversed entirely after eliminating the underlying cause.7Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

Clinical Presentation of Sideroblastic Anemia

The most common symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Headache

- Malaise

- Palpitations

- Pale skin

- Dizziness

- Abnormal heart rhythms

Children suffering from SA often develop severe symptoms. These symptoms include:

- Developmental delay

- Exertional dyspnea

- Feeding intolerance

- Irritability

- Jaundice

- Growth retardation

- Vertigo

Diagnosis of Sideroblastic Anemia

Sideroblastic Anemia is primarily a laboratory diagnosis.

History & Physical Examination:

The condition needs a thorough physical examination. The physical findings indicative of SA include:

- Conjunctival pallor

- Tachycardia

- Pale skin

- Bronze-colored skin due to iron overload

- Severe chronic forms of SA associated with MDS will represent mild hepatosplenomegaly.

- People with syndromic hereditary SA can present deafness and uncontrolled diabetes.

- Younger patients with a family history will represent hereditary types of SA. Older patients usually represent acquired SA.

- Clinicians will review all the potential social exposures, such as work-related exposures, surgical procedures, social exposures, use of medications, and consumption of alcohol. They will look for the past medical history of cancer and familial hematologic malignancies. Additionally, a history of gastrointestinal surgery or excessive zinc intake can suggest copper deficiency, a well-known cause of acquired SA.8Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

Laboratory Evaluations:

A complete blood count (CBC), peripheral blood smear, and iron studies are necessary for initial assessment. Genetic testing can help identify inherited causes of the disorder.

Blood Tests

CBC evaluates red blood cell production, size, and hemoglobin levels, helping to assess anemia. A comprehensive metabolic panel with vitamin and mineral assessments is necessary to detect deficiencies contributing to SA. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) helps differentiate between different types of SA.9Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

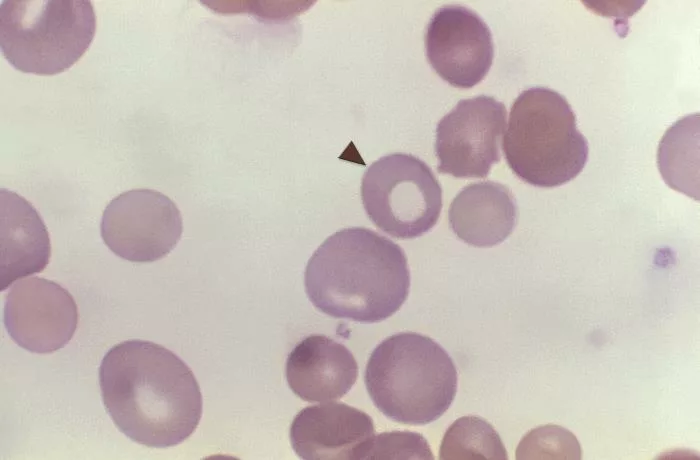

Peripheral Blood Smear

The health care provider will examine the blood smear under a microscope to identify the characteristics and features (morphology of red blood cells, whether hypochromic or microcytic.10Camaschella, C. Hereditary sideroblastic anemias: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. in Seminars in hematology. 2009. Elsevier.

Iron Studies

These studies assess the extent of iron overload, determining the necessity for phlebotomy and ongoing therapy. Iron studies measure serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin saturation to evaluate iron stores. In individuals with confirmed iron overload, liver biopsy and magnetic resonance imaging accurately assess the severity of the iron stores in the tissues.

Bone Marrow Examination

Bone marrow examination includes bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. During bone marrow aspirations, the providers take a sample of the liquid part of your bone marrow. Prussian blue staining of the bone marrow aspirate smear will show typical ring sideroblasts under the microscope. The sample obtained through bone marrow biopsy also indicates the ring sideroblasts, a hallmark of the SA.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing can identify the specific mutations responsible for SA, helping determine whether the condition is hereditary and potentially transmissible to offspring.

Treatment & Management of Sideroblastic Anemia

Management of the SA depends on the severity of the condition.

Treatment of Sideroblastic Anemia with Mid or Asymptomatic Presentation:

The drugs used to treat this type of SA include:

- Oral pyridoxine (50-100mg/day) can partially or entirely correct anemia, especially X-linked SA.11Camaschella, C. Hereditary sideroblastic anemias: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. in Seminars in hematology. 2009. Elsevier.

- Luspatercept is beneficial in treating congenital SA as it promotes erythroid maturation. The recommended dose of luspatercept is 1 mg/kg after every three weeks.12Van Dijck, R., A.M. Goncalves Silva, and A.W. Rijneveld, Luspatercept as potential treatment for congenital sideroblastic anemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2023. 388(15): p. 1435-1436.

Blood transfusions may be necessary for patients who do not respond adequately to pyridoxine therapy. The providers consider iron chelation for those patients who require chronic transfusions to prevent iron overload.

Treatment of Sideroblastic Anemia with Severe or Symptomatic Presentation:

For severe or symptomatic SA, treatment options include growth factors, hypomethylating agents (HMAs), and novel therapies.

- Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF) and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) help stimulate blood cell production.

- Hypomethylating agents (HMAs), such as decitabine and azacytidine (75 mg/m² for seven days in a 28-day cycle), are used when G-CSF and ESAs fail.13Greenberg, P.L., et al., NCCN Guidelines® insights: myelodysplastic syndromes, version 3.2022: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2022. 20(2): p. 106-117.

- Imetelstat, a telomerase inhibitor, is a promising new treatment for MDS-related SA.14Platzbecker, U., et al., Imetelstat in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have relapsed or are refractory to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (IMerge): a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 2024. 403(10423): p. 249-260.

Preventive Measures

You cannot avoid congenital SA, but you can prevent acquired SA by following simple things.

- Limit your alcohol consumption.

- Avoid accidental exposures to arsenic and lead.

- Try to limit the intake of iron-rich foods. Adequate intake of essential nutrients is necessary.

- Educating patients and caregivers about the disease. Educating people about the triggers and their complications is a plus point for effective prevention and management of the disorder.

Complications Associated with Sideroblastic Anemia

SA can lead to iron overload, which accumulates in organs and increases the risk of complications such as cirrhosis and fibrosis.

In rare cases, patients may also develop:

- Endocrine dysfunction (e.g., diabetes mellitus)

- Cardiomyopathy due to iron deposition in the heart

- Hepatomegaly (enlarged liver)

- Leukopenia (low white blood cell count)

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

- Vascular complications such as clotting disorders15Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

Prognosis

The prognosis of SA varies according to the underlying cause. Adequate pyridoxine supplementation and management of iron overload can significantly improve outcomes in X-linked SA. However, co-occurring mutations can influence the prognosis. In the case of secondary acquired SA, the prognosis can be favorable after the discontinuation of the causative toxic agents or drugs.

Sideroblastic Anemia vs. Thalassemia

SA and Thalassemia are disorders that affect red blood cell production. They differ in their causes and characteristics. The key differences are in the Table.

| Sideroblastic Anemia | Thalassemia |

| Sideroblastic anemia is a rare disorder in which bone marrow produces ring sideroblasts instead of producing healthy red blood cells. | Thalassemia is an inherited disorder affecting alpha or beta-globin chain synthesis, leading to defective erythropoiesis. |

| Genetic SA

It occurs due to genetic mutations affecting mitochondrial function or heme synthesis. Acquired SA They can be acquired through certain metals, drugs, and medications and be part of MDs. |

Alpha-Thalassemia

Mutations affecting the α globin chain production cause alpha-thalassemia. Beta-Thalassemia Mutations affecting the β-globin chain production cause beta-thalassemia. |

| The most common symptoms include fatigue, headache, and weakness. | Symptoms range from mild anemia to severe transfusion-dependent anemia. |

| Diagnosis includes bone marrow examination. | Diagnosis includes hemoglobin electrophoresis.16Cattivelli, K., et al., Ringed sideroblasts in β‐thalassemia. Pediatric blood & cancer, 2017. 64(5): p. e26324. |

Final Remarks

SA occurs due to ineffective erythropoiesis. It encompasses both inherited and acquired conditions. Impaired heme synthesis in these conditions leads to the accumulation of ring sideroblasts in the bone marrow. The treatment regimens focus on addressing the underlying causes. Supportive care can manage mild to moderate symptoms of the disorder. However, there is no curative therapy for congenital forms of SA except for STEM cell transfusions. People with a family history of it are more vulnerable to the disease.

Refrences

- 1Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

- 2Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

- 3Furuyama, K. and K. Kaneko, Iron metabolism in erythroid cells and patients with congenital sideroblastic anemia. International Journal of Hematology, 2018. 107: p. 44-54.

- 4. Ducamp S, Fleming MD: The molecular genetics of sideroblastic anemia. Blood 133:59–69, 2019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-08-815951

- 5Patnaik, M.M. and A. Tefferi, Refractory Anemia with Ring Sideroblasts (RARS) and RARS with Thrombocytosis (RARS-T)–“2019 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-stratification, and Management”. American journal of hematology, 2019. 94(4): p. 475.

- 6Rodriguez-Sevilla, J.J., X. Calvo, and L. Arenillas, Causes and pathophysiology of acquired sideroblastic anemia. Genes, 2022. 13(9): p. 1562.

- 7Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

- 8Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

- 9Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

- 10Camaschella, C. Hereditary sideroblastic anemias: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. in Seminars in hematology. 2009. Elsevier.

- 11Camaschella, C. Hereditary sideroblastic anemias: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. in Seminars in hematology. 2009. Elsevier.

- 12Van Dijck, R., A.M. Goncalves Silva, and A.W. Rijneveld, Luspatercept as potential treatment for congenital sideroblastic anemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2023. 388(15): p. 1435-1436.

- 13Greenberg, P.L., et al., NCCN Guidelines® insights: myelodysplastic syndromes, version 3.2022: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2022. 20(2): p. 106-117.

- 14Platzbecker, U., et al., Imetelstat in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have relapsed or are refractory to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (IMerge): a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 2024. 403(10423): p. 249-260.

- 15Ashorobi, D. and A. Chhabra, Sideroblastic anemia. StatPearls [Internet], 2024.

- 16Cattivelli, K., et al., Ringed sideroblasts in β‐thalassemia. Pediatric blood & cancer, 2017. 64(5): p. e26324.