Anthrax is a severe infectious disease. The bacteria Bacillus anthracis causes this disorder. B. anthracis is a small, encapsulated, facultatively anaerobic or aerobic, gram-positive, and spore-forming bacterium. It is a rod-shaped bacterium with square ends. It typically measures 3 to 5 micrometers long and 1 to 1.2 micrometers wide and often appears in long chains resembling bamboo stalks.1Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

The bacteria produce toxins for their clinical virulence. These toxins include protective antigen (PA), edema factor (EF), and lethal factor (LF), which contribute to disease severity. The name of the disorder comes from the Greek word ‘anthrakis,’ which refers to a necrotic lesion observed in cutaneous form. The disease can affect the skin and internal organs, presenting prodromal symptoms such as sweating, nausea, vomiting, and fever.2Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity. When inhaled, the bacteria can be fatal, leading to respiratory failure and hemodynamic collapse. However, symptoms typically appear within 1 to 7 days but can be delayed for up to 60 days due to spore dormancy.3Zacchia, N.A. and K. Schmitt, Medical spending for the 2001 anthrax letter attacks. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 2019. 13(3): p. 539-546.

The disease occurs worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the estimated annual global incidence ranges between 2,000 and 20,000 cases, primarily in regions where livestock vaccination is inadequate. There are four types of anthrax: cutaneous, injection, gastrointestinal, and inhalational anthrax. The mortality rates vary depending on the type.4Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

Causes & Transmission

Bacillus anthracis spores contaminate soil and remain viable in the environment for decades, particularly in endemic regions. Animal anthrax cases commonly occur in the summer and early fall, especially in areas where environmental conditions favor spore activation. Herbivores contract the infection by ingesting or inhaling spores while grazing. The most frequently affected mammals include domestic sheep, cattle, goats, wild deer, and antelopes.

Humans acquire anthrax through contact with infected animals, handling contaminated hides, butchering infected livestock, or consuming undercooked or raw meat. Infection occurs through skin contact, ingestion, or inhalation of spores. While inhalational anthrax can also occur in industrial settings where spores become aerosolized, there is no evidence of direct human-to-human transmission of the disease.

Mechanism of Infection

Livestock become infected by ingesting or inhaling anthrax spores while grazing in contaminated areas. Once inside the body, the spores germinate, and the bacteria multiply in the bloodstream, leading to systemic infection. Infected animals shed bacteria through their feces, urine, and other bodily fluids. Carcasses of animals that die from anthrax contain large amounts of bacteria, which sporulate upon exposure to oxygen.5Kamal, S., et al., Anthrax: an update. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine, 2011. 1(6): p. 496-501. Once formed, anthrax spores contaminate surrounding soil, water, and vegetation, perpetuating the disease cycle.

Humans acquire anthrax through various routes. The cutaneous form occurs when spores enter the skin through cuts or abrasions, often due to handling infected animals or contaminated products. The inhalational form results from breathing in aerosolized spores, while the gastrointestinal form develops after consuming undercooked contaminated meat.

Inside the human body, spores are taken up by macrophages and transported to lymph nodes, where they germinate and release toxins. The toxins disrupt blood vessels, cause hemorrhage, and lead to sepsis, resulting in severe clinical symptoms.6Williamson, E.D. and E.H. Dyson, Anthrax prophylaxis: recent advances and future directions. Frontiers in microbiology, 2015. 6: p. 1009.

Types of Anthrax

The four types are as follows:

Cutaneous Anthrax:

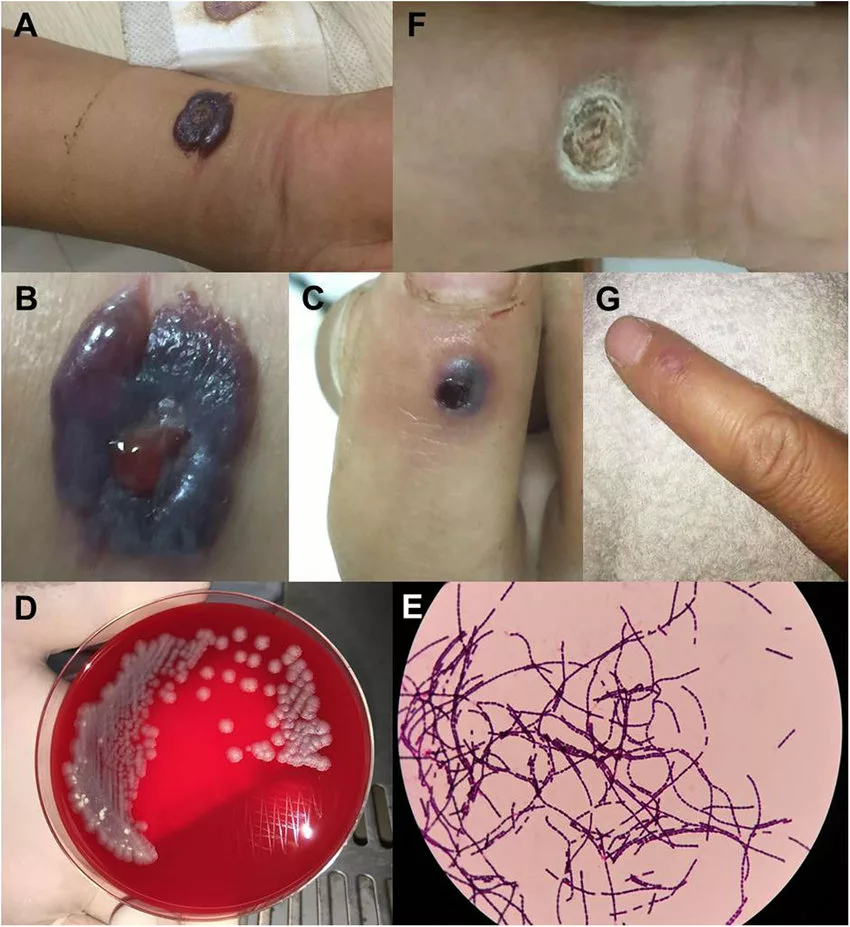

It is the most common type and occurs when B. anthracis spores enter through broken skin, typically from handling infected animals or contaminated animal products. It accounts for more than 95% of human cases.7Doganay, M., G. Metan, and E. Alp, A review of cutaneous anthrax and its outcome. Journal of infection and public health, 2010. 3(3): p. 98-105. It is characteristically a local skin infection that often occurs on the hands, arms, neck, and face. The lesion starts as a pruritic papule. It then progresses to a vesicle and into the typical black necrotic eschar. Moderate cutaneous anthrax has a <2% mortality rate upon adequate treatment. On the other hand, the mortality rate can be high (30% ) if localized infections advance to their systemic form.8Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Injection Anthrax:

This one is a comparatively new form of the infection. It occurs exclusively in drug users, and its cases have been reported only in Europe. Symptoms resemble severe soft tissue infections but lack the characteristic black eschar of cutaneous anthrax. It can lead to deep tissue infections (myositis, necrotizing fasciitis), which may lead to sepsis and multi-organ failure. The mortality rate of injection anthrax is about 25%, however, but in rare cases, it can exceed 90%.9Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax:

This form is caused by ingestion of spores from undercooked contaminated meat.The gastrointestinal type occurs when the spores of anthrax germinate in and affect the lower gastrointestinal tract of humans. It results in gastrointestinal problems such as bloody diarrhea. The estimated mortality rate of this type of anthrax is around 74%. However, healthcare providers can substantially mitigate mortality rates with early and appropriate treatment.10Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Inhalational Anthrax:

It results from the inhalation of aerosolized spores. It leads to the accumulation of bacterial spores in the alveoli of the lungs. Immune cells engulf spores and transfer them to the regional lymph nodes, where they germinate. It multiplies and starts producing toxins. Symptoms start mild (fever, cough, fatigue) but rapidly progress to severe respiratory distress, sepsis, and shock. The mortality rate of inhalational anthrax is around 72%.11Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Symptoms of Anthrax in Animals

The clinical course of this infection in animals varies from acute to chronic presentations. The acute form can affect herbivores without any previous signs of the infection. The symptoms of acute form in animals include:

- Dyspnea

- Shaking

- Staggering

- Collapse

- Convulsive movements

- Partial rigor mortis

- Dark, tar-like discharge from the vulva

- Dark blood in the nostrils and mouth

- A sudden increase in the temperature

- Depression

- Respiratory problems

- Cardiac problems

In horses and pigs, the symptoms include:

- Fever

- Edema

- Lethargy

- Anorexia

- Petechial hemorrhages on the skin

- Subcutaneous edema (localized) is most prevalent in the chronic type.12Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

Symptoms of Anthrax in Humans

Symptoms of this infection vary with its different types.

Cutaneous Anthrax

- Symptoms begin as a pruritic papule that progresses into a painless ulcer with associated satellite vesicles. Over a few days, it develops a necrotic black center surrounded by non-pitting edema, a hallmark sign.

- Cutaneous anthrax lesions are usually painless, distinguishing them from other infectious lesions.

Injection Anthrax

- Starts with small papules or vesicles at the injection site. These rapidly evolve into painless ulcerative lesions, often without a black eschar.

- Progression is often systemic, leading to severe illness, unlike the more localized cutaneous form.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax

Gastrointestinal anthrax presents oropharyngeal or intestinal symptoms. People with oropharyngeal anthrax develop:

- Oropharyngeal ulcers

- Cervical swellings

- Dysphagia

- Regional lymphadenopathy

People with intestinal anthrax may experience:

- Fever

- Vomiting

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

They may progress to hematemesis (vomiting blood), bloody diarrhea, massive ascites, and septicemia if untreated.

Inhalational Anthrax

Inhalational anthrax presents symptoms in the non-specific prodromal stage, including:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Sweats

- Chest pain

- Malaise

- Non-reproductive cough

A second stage of illness results in:

- Mediastinitis

- Hemorrhagic lymphadenitis

- Bacteremia

- Meningitis in most severe cases

- Respiratory failure

- Hemodynamic collapse13Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.

Risk Factors of Anthrax

People who have to work with animal products such as bone, bone products, skin, hair, meat, and wool are more susceptible to the infection. Veterinarians, animal health officers, livestock workers in prevalent areas, and laboratory workers who handle the samples of this infection are among the high-risk groups. Additionally, people who do not wear footwear while engaging in outdoor activities such as walking or playing in the fields can increase the risk of contracting anthrax spores.14Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

Diagnosis of Anthrax

Early diagnosis is essential for the efficient treatment and management of the disease. The diagnosis includes assessing the patient’s history, clinical symptoms and signs, laboratory inspection, radiological examination, and microbiological testing.

Clinical Assessment:

Healthcare providers first assess the patient’s history for potential exposure to anthrax. Residence in an endemic region and occupations involving animal handling, exposure to sick or dead animals, or contact with contaminated animal products are significant risk factors. Additionally, doctors evaluate symptoms specific to each type of anthrax to guide further testing.

Laboratory Assessment:

The laboratory assessment includes the following tests:

Microbiological Test

Microbiological testing is the gold standard for diagnosing this disease. This test includes culturing blood, lesions, or cerebrospinal fluid specimens. The presence of B. anthracis in the cultures confirms the diagnosis.15Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The healthcare provider uses real-time PCR to diagnose this infection. The presence of B. anthracis DNA in the blood or tissue samples confirms the presence of the bacteria.

Serology

The provider can ask for blood tests for confirmation. Abnormal test results indicate antibodies produced against B. antharcis in the blood. However, this test is more valuable in the later disease course as an increase in the antibody level over time can confirm active infection.

Radiological Examination

Chest X-rays and CT scans can diagnose inhalation anthrax by identifying the pleural effusion and mediastinal widening.16Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Other Diagnostic Modalities:

- Spinal tap for the diagnosis of anthrax meningitis

- Stool tests for diagnosing gastrointestinal anthrax

- Biopsy for cutaneous anthrax

Treatment & Management

Treatment and management of this infectious disease include antibiotics, antitoxin in some cases, and supportive care. Fast treatment with antibiotics can stop the infection from progressing.

Cutaneous Anthrax:

Antibiotic therapy is the primary treatment for this infection. In mild or uncomplicated cases, intramuscular penicillin G or oral antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin or doxycycline are effective monotherapy options. However, in severe or complicated cases, doctors recommend intravenous antibiotic administration. Supportive care includes dressing and covering lesions with a sterile wrap during the acute inflammatory phase. Surgical intervention is generally avoided, as it can lead to bacterial dissemination and poor outcomes.17Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

Injectional Anthrax:

Surgical debridement of infected soft tissues, combined with antibiotic therapy and supportive care, is critical for managing this form of anthrax. Early intervention can be life-saving.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax:

Doctors recommend initial intravenous antibiotic therapy, typically ciprofloxacin or doxycycline, in combination with additional antibiotics such as clindamycin, rifampin, or a carbapenem. Early surgical removal of necrotic intestinal tissue with primary anastomosis may be necessary in severe cases to improve survival outcomes.

Inhalational Anthrax:

The preferred treatment regimen includes ciprofloxacin or doxycycline, combined with at least one or two additional antibiotics such as rifampin, clindamycin, or meropenem. Patients with respiratory failure may require mechanical ventilation, and pleural space drainage can reduce ventilation duration.18Hendricks, K.A., et al., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel meetings on prevention and treatment of anthrax in adults. Emerging infectious diseases, 2014. 20(2): p. e130687.

For meningoencephalitis caused by anthrax, combination therapy with ciprofloxacin or meropenem plus linezolid is recommended instead of penicillin G and rifampin.19Doganay, M. and G. Metan, Human anthrax in Turkey from 1990 to 2007. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 2009. 9(2): p. 131-140

Precautions & Preventive Measures

If you are traveling to an area known to have this problem, then avoid:

- Eating raw or undercooked meat

- Touching pets and wild animals

- Buying thind made up of animal hide and hairs.

- Get a vaccine.

The vaccine for this infection is effective in preventing the infection. However, it is only available for people between 18 and 65. It is available for people who work in high-risk professions, including veterinarians, farmers, military members, livestock handlers, researchers, and other workers.

Anthrax Vaccine

The Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA) is the most widely used vaccine in the United States. It contains protective antigen (PA) as the primary immunizing component. The vaccination schedule consists of three doses given at zero, two, and four weeks, followed by booster doses at 6, 12, and 18 months. Annual boosters help maintain immunity.

In Russia, healthcare providers use a live spore vaccine (STI) administered in a two-dose regimen. The Anthrax Vaccine Precipitated (AVP) is licensed in the United Kingdom and follows a three-dose schedule with a six-month booster and annual boosters to sustain protection.20Splino, M., et al., Anthrax vaccines. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 2005. 25(2): p. 143-149.

Differential Diagnosis

It varies with its different types. The differential diagnosis of cutaneous anthrax is:

- Spider bite

- Cat Scratch

- Ecthyma gangrenosum

- Staphylococcal skin abscess

The differential diagnosis of inhalational anthrax includes:

- Tularemia

- Pneumonia plague

- Respiratory syncytial virus

- Influenza

- Community-acquired pneumonia

The differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal diagnostic considerations include:

- Bubonic plague

- Ulceroglandular tularemia21Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.

Prognosis

The majority of the cases are cutaneous and they resolve with treatment. When treated promptly with antibiotics, the estimated mortality rate is usually less than 2%. Inhalational anthrax is the most life-threatening form of this infection, which carries a poor prognosis. The reported mortality rate of inhalational anthrax is 50%, even with adequate treatment.22Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.

Final Review

This is a hazardous infectious disease. Its spores are resistant to extreme environments, making it a prospective biological deterrent. Transmission of the bacterial spores can be through soil and aerosols. This infection presents a diverse set of clinical illnesses. It can lead to fetal consequences that are usually difficult to diagnose and treat. Healthcare providers should raise public awareness to help them avoid getting the infection.

Refrences

- 1Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

- 2Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.

- 3Zacchia, N.A. and K. Schmitt, Medical spending for the 2001 anthrax letter attacks. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 2019. 13(3): p. 539-546.

- 4Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

- 5Kamal, S., et al., Anthrax: an update. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine, 2011. 1(6): p. 496-501.

- 6Williamson, E.D. and E.H. Dyson, Anthrax prophylaxis: recent advances and future directions. Frontiers in microbiology, 2015. 6: p. 1009.

- 7Doganay, M., G. Metan, and E. Alp, A review of cutaneous anthrax and its outcome. Journal of infection and public health, 2010. 3(3): p. 98-105.

- 8Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 9Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 10Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 11Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 12Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

- 13Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.

- 14Khairullah, A.R., et al., Anthrax disease burden: Impact on animal and human health. International Journal of One Health, 2024. 10(1): p. 45-55.

- 15Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 16Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 17Bower, W.A., et al., What is anthrax? Pathogens, 2022. 11(6): p. 690.

- 18Hendricks, K.A., et al., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel meetings on prevention and treatment of anthrax in adults. Emerging infectious diseases, 2014. 20(2): p. e130687.

- 19Doganay, M. and G. Metan, Human anthrax in Turkey from 1990 to 2007. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 2009. 9(2): p. 131-140

- 20Splino, M., et al., Anthrax vaccines. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 2005. 25(2): p. 143-149.

- 21Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.

- 22Simonsen, K.A. and J. Snowden, Continuing Education Activity.