Psittacosis is a zoonotic bacterial infectious disease. An obligate intracellular organism, Chlamydia psittaci, causes this disorder. Other names for this disorder are ornithosis and parrot fever. Its transmission occurs after contact with the infected birds. It can cause a broad range of symptoms, from mild flu-like illness to severe pneumonia. Birds are the major epidemiological reservoirs of the disorder. Researchers have identified and documented this disease process in 467 different species of birds.1Stewardson, A.J. and M.L. Grayson, Psittacosis. Infectious Disease Clinics, 2010. 24(1): p. 7-25.

Psittacosis can affect people of any age and gender. Its incidence peaks in middle age, usually aged 35 to 55 years. The reported incidence of psittacosis in the United States is 0.01 per 100,000 population.2Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019. It has been reported worldwide and is usually sporadic, while outbreaks have also been reported. The outbreaks are associated with veterinary facilities, poultry farms, and pet shops.3Stewardson, A.J. and M.L. Grayson, Psittacosis. Infectious Disease Clinics, 2010. 24(1): p. 7-25.

Causes

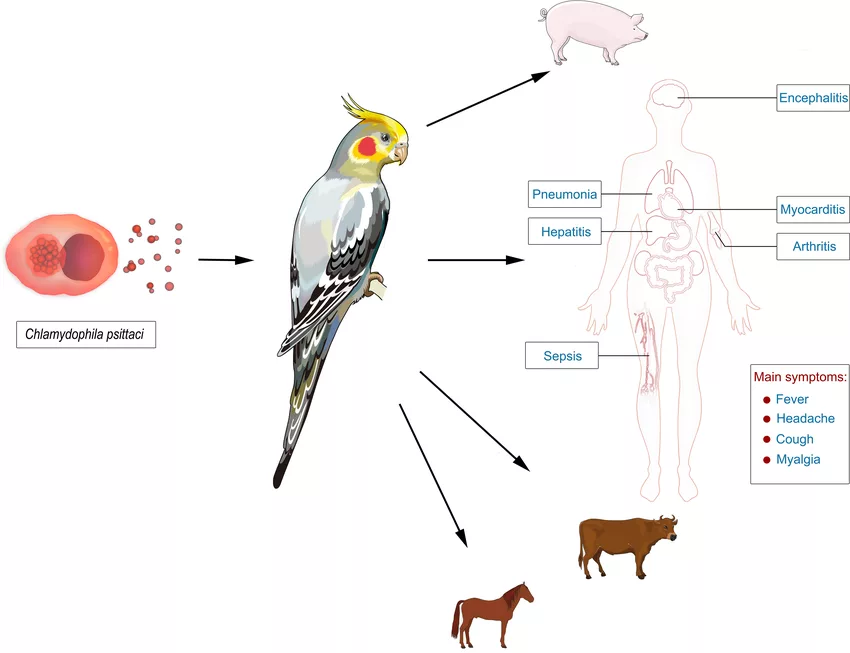

C. psittaci is an obligate, intracellular, gram-negative bacterium. It possesses multiple genotypes. Each genotype is associated with a specific animal host, which can later transmit the infection to humans. Contact with birds is the primary risk factor for psittacosis in humans, although indirect exposure to contaminated environmental factors—such as secretions, urine, and feces of infected birds—can also lead to infection.4Balsamo, G., et al., Compendium of measures to control Chlamydia psittaci infection among humans (psittacosis) and pet birds (avian chlamydiosis), 2017. Journal of avian medicine and surgery, 2017. 31(3): p. 262-282.

Parrots, budgies, parakeets, and cocktails are the most common birds that are the source of this disease. Poultry birds, including turkeys, ducks, and chickens, have also been linked to outbreaks, particularly in poultry farms.5Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.6McGovern OL, Kobayashi M, Shaw KA, Szablewski C, Gabel J, Holsinger C, Drenzek C, Brennan S, Milucky J, Farrar JL, Wolff BJ, Benitez AJ, Thurman KA, Diaz MH, Winchell JM, Schrag S. Use of Real-Time PCR for Chlamydia psittaci Detection in Human Specimens During an Outbreak of Psittacosis – Georgia and Virginia, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Apr 9;70(14):505-509. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7014a1. PMID: 33830980; PMCID: PMC8030988.

Modes of Transmission

The various modes of transmission are as follows:

Transmission from Bird to other Birds:

Researchers regard psittacosis as an avian chlamydiosis in birds. Infected birds can shed Chlamydia psittaci bacteria through their feces, respiratory secretions, and feather dust for an extended period, sometimes even months. The bacteria remain viable in dried feces and dust, allowing for airborne transmission. While some birds may develop partial immunity, reinfection is possible, especially under stress or compromised health conditions.7Balsamo, G., et al., Compendium of measures to control Chlamydia psittaci infection among humans (psittacosis) and pet birds (avian chlamydiosis), 2017. Journal of avian medicine and surgery, 2017. 31(3): p. 262-282.

Transmission from Birds to Humans:

Humans primarily contract C. psittaci by inhaling aerosolized particles from contaminated bird droppings, feather dust, or respiratory secretions. Handling infected bird tissues in the laboratory can also play a part in transmitting the disease. However, some people experience the symptoms without having a bird exposure history. Sometimes, even momentary exposures can cause symptoms.8Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

Person to Person Transmission:

Researchers believed that psittacosis can hardly be transferred via direct human-to-human contact. While there have been isolated reports suggesting the possibility, no conclusive evidence has confirmed sustained person-to-person spread.9Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.10Wallensten A, Fredlund H, Runehagen A. Multiple human-to-human transmission from a severe case of psittacosis, Sweden, January-February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014 Oct 23;19(42):20937. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.42.20937. PMID: 25358043.

Life Cycle of C. psittaci

C. psittaci has a developmental cycle with two forms. This organism has a larger metabolically active intracellular reticulate body in addition to an extracellular infectious elementary body. After exposure to a host’s eukaryotic cell, the infectious elementary body becomes endocytosed into the cell. It happens after the interaction of the bacterium with the cell membrane receptor of the host cell. Hence evading the response of the host immune system.

The endocytosed elementary body increases in size, forming a metabolically active reticulate body that undergoes binary fission utilizing ATP from the host cell. As the infection progresses, RBs reorganize into intermediate forms before converting back into EBs. These newly formed EBs are released through cell lysis, allowing the bacteria to spread and infect new host cells, continuing the cycle. They propagate the cycle of the disease and spread through the hematogenous route to the other organ systems.11Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.

Pathophysiology/Pathogenesis

The exact pathophysiology is not fully elucidated. However, studies suggest that the infection primarily begins in alveolar epithelial cells, triggering an immune response. The initial infection initiates a complex host response, leading to an influx of neutrophils. The response is mediated through chemokine release (more significantly, interleukin-8). It leads to the activation of the reactive oxygen species and an inflammatory cascade. This activation triggers further recruitment and accumulation of immune cells and phagocytes from the bloodstream to the infection site.

All this process results in the breakdown of the alveolar-capillary membrane and tissue damage and enables the hematogenous spread of the bacterium. Infected individuals may experience impaired oxygen exchange, leading to hypoxemia, reduced lung compliance, and alveolar hypoventilation.12Knittler, M.R., et al., Chlamydia psittaci: New insights into genomic diversity, clinical pathology, host-pathogen interaction, and anti-bacterial immunity. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2014. 304(7): p. 877-893.

Symptoms of Psittacosis

The onset of the symptoms is sudden. The common symptoms include:

- Headache

- Fever

- Diarrhea

- Nausea

- Cough

- Myalgia

Other signs include:

- Mild neck stiffness

- Altered mental status

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Photophobia

- Pharyngitis13Stewardson, A.J. and M.L. Grayson, Psittacosis. Infectious Disease Clinics, 2010. 24(1): p. 7-25.

Psittacosis can affect several organs and organ systems. The clinical manifestations of different psittacosis in different organ systems are as follows:

Cardiac Manifestations:

They are rare but can include:

- Pericarditis

- Aortitis

- Culture-negative endocarditis

- Myocarditis

Respiratory Manifestations:

- Pneumonia

- Respiratory failure

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Septic shock

Manifestations of the Central Nervous System:

- Meningoencephalitis

- Transverse myelitis

- Status epileptics

- Guillian-Barre syndrome

- Cerebellar ataxia

- Cranial nerve palsies

Hematological Manifestations:

- Hemophagocytic syndrome

- Splenomegaly

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Gastrointestinal or Renal Manifestations

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatitis

- Acute interstitial nephritis

- Glomerulonephritis

- Acute renal failure

Rheumatological Manifestations:

- Polyarteritis

- Reactive arthritis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of psittacosis involves several methods due to the non-specific symptoms of the disease.

Clinical Considerations:

The healthcare provider first looks at the symptoms of the condition. Diagnosis mostly depends on taking a detailed history involving the medical history and travel history. The clinician will perform a thorough patient interview involving an occupational history, hobbies, travel history, and a strong suspicion of getting an infection.

Laboratory Tests:

The laboratory tests include the following:

Blood Tests

The initial phase of the infection reports a slight decrease in leukocyte count. The acute phase represents leukopenia, and hemolysis can lead to anemia.

Liver Function Tests

Liver function tests indicate high levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Additionally, they also indicate elevated levels of C-reactive protein.14Longbottom, D. and L. Coulter, Animal chlamydioses and zoonotic implications. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 2003. 128(4): p. 217-244.

Culture Method

The culture method is the most accurate and specific method for diagnosing this disease. However, isolation of C. psittaci requires biosafety as there is a significant risk of transmission by laboratory workers. Isolations can be through respiratory tract secretions such as throat swabs and sputum.15Favaroni, A., et al., Pmp repertoires influence the different infectious potential of avian and mammalian Chlamydia psittaci strains. Frontiers in microbiology, 2021. 12: p. 656209.

Serology

Serological tests can confirm the suspected cases of psittacosis. The most common serological tests are micro-immunofluorescent antibody tests (MIF) and complement fixation (CF). MIF is more specific and sensitive for diagnosing C. psittaci than CF.16Mi, H., H. Li, and J. Yu, Psittacosis. Radiology of Infectious Diseases: Volume 2, 2015: p. 207-212.

Imaging Tests:

Chest X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) help diagnose the disease. Most patients exhibit abnormal chest X-rays involving pleural effusions and migratory infiltrates. MRI diagnoses the neurological issues associated with the disease.17Mi, H., H. Li, and J. Yu, Psittacosis. Radiology of Infectious Diseases: Volume 2, 2015: p. 207-212.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR):

PCR helps identify the source of infection by genotyping and helps rapidly detect psittacosis patients. It is a highly sensitive method for detecting the acute phase of the disease.18Nieuwenhuizen, A.A., et al., Laboratory methods for case finding in human psittacosis outbreaks: a systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2018. 18: p. 1-16.

Treatment & Management of Psittacosis

Antibiotics are the primary treatment of psittacosis. The most commonly prescribed antibiotics are doxycycline and tetracycline, typically for 10 to 14 days. In cases where oral administration is not possible, intravenous doxycycline is recommended at a dose of 100 mg.19Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

Treatment for Infants & Pregnant Women

For infants, the clinicians recommend azithromycin. For pregnant patients, the recommended antibiotics are azithromycin (five-day course) and erythromycin (seven-day course). Healthcare providers can also recommend fluoroquinolones, which are less efficient than azithromycin and tetracyclines.20Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

Differential Diagnosis

Several disorders might have symptoms similar to parrot fever or psittacosis. These include

- Influenza

- Tularemia

- Legionella pneumonia

- Mycoplasma pneumonia

- Typhoid fever

- Q fever

- Viral pneumonia

- Fungal infection

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Bird Flu (Avian Influenza)

- Brucellosis

Psittacosis Vs. Bird-Flu

The major diagnostic difference between Bird Flu and Psittacosis lies in their causative agents (virus vs. bacterium), transmission sources (poultry vs. pet birds), and symptom profiles.

| Bird Flu | Psittacosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Causative Agent | Influenza A virus (H5N1, H7N9, etc.) | Chlamydia psittaci (bacterium) |

| Transmission | Primarily through infected poultry | Through infected pet birds (e.g., parrots) |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches | Fever, cough, headache, myalgia, diarrhea |

| Liver Involvement | Rare | Common (elevated liver enzymes) |

| Neurological Impact | Rare | Can include encephalitis, seizures |

| Diagnosis | RT-PCR, viral cultures | Serology, PCR, culture, imaging |

| Treatment | Antiviral drugs (e.g., oseltamivir) | Antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline, azithromycin) |

| Complications | Respiratory failure, pneumonia | Pneumonia, organ damage (liver, CNS) |

Prognosis

With proper antibiotic treatment, the cure rate for psittacosis is reported to be around 94.23%. The mortality rate is low (approximately 1% or less) when appropriate treatment is administered. However, untreated psittacosis can lead to significant complications. Gestational psittacosis, though rare, can cause both maternal and fetal mortality.21Li, X., et al., Clinical, radiological and pathological characteristics of moderate to fulminant psittacosis pneumonia. PLoS One, 2022. 17(7): p. e0270896.22Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.

Complications

Complications of psittacosis occur due to hematogenous spread of C. psittaci to various organ systems. These include:

- Respiratory failure

- Pneumonia

- Hepatitis

- Endocarditis

- Pancreatitis

- Encephalitis

- Multiple organ failure

Prevention & Control

Still, there is no vaccine available to prevent this infection. So, control of the disease is only possible when we can limit the spread of the bacteria. The preventive and control measures are the following:

- Provide proper guidance to the people when dealing with the birds and bird’s houses. It can restrict the spread of the disease.

- Ensure wearing personal protective equipment such as masks, gloves, and gowns while dealing with birds and their cages.

- You must consult the healthcare provider and veterinarians if you have doubts about the bird carrying the infection.

- Educate the people at risk and the healthcare providers about the signs and workup of the disease.

- Educate the public about the proper handling of the birds.

- A combined and coordinated public healthcare personnel and health department effort can aid in educating the industry on maintaining accurate records of all bird-related transactions. This record can identify the source of infection in the future.

- Use appropriate disinfectants on all the exposed surfaces.

- Additionally, quarantine of the exposed and ill bids can limit the spread of the disease.

A Quick Review

Psittacosis is an overlooked zoonotic disease. The most common route of the infection is the inhalation of the excreted substances of the birds. The clinical signs of the disease range from mild to severe complications. Pharmacotherapy is the first-line treatment of psittacosis. Rush immediately to your healthcare provider after exposure to an infected bird.

Refrences

- 1Stewardson, A.J. and M.L. Grayson, Psittacosis. Infectious Disease Clinics, 2010. 24(1): p. 7-25.

- 2Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.

- 3Stewardson, A.J. and M.L. Grayson, Psittacosis. Infectious Disease Clinics, 2010. 24(1): p. 7-25.

- 4Balsamo, G., et al., Compendium of measures to control Chlamydia psittaci infection among humans (psittacosis) and pet birds (avian chlamydiosis), 2017. Journal of avian medicine and surgery, 2017. 31(3): p. 262-282.

- 5Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.

- 6McGovern OL, Kobayashi M, Shaw KA, Szablewski C, Gabel J, Holsinger C, Drenzek C, Brennan S, Milucky J, Farrar JL, Wolff BJ, Benitez AJ, Thurman KA, Diaz MH, Winchell JM, Schrag S. Use of Real-Time PCR for Chlamydia psittaci Detection in Human Specimens During an Outbreak of Psittacosis – Georgia and Virginia, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Apr 9;70(14):505-509. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7014a1. PMID: 33830980; PMCID: PMC8030988.

- 7Balsamo, G., et al., Compendium of measures to control Chlamydia psittaci infection among humans (psittacosis) and pet birds (avian chlamydiosis), 2017. Journal of avian medicine and surgery, 2017. 31(3): p. 262-282.

- 8Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

- 9Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

- 10Wallensten A, Fredlund H, Runehagen A. Multiple human-to-human transmission from a severe case of psittacosis, Sweden, January-February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014 Oct 23;19(42):20937. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.42.20937. PMID: 25358043.

- 11Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.

- 12Knittler, M.R., et al., Chlamydia psittaci: New insights into genomic diversity, clinical pathology, host-pathogen interaction, and anti-bacterial immunity. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2014. 304(7): p. 877-893.

- 13Stewardson, A.J. and M.L. Grayson, Psittacosis. Infectious Disease Clinics, 2010. 24(1): p. 7-25.

- 14Longbottom, D. and L. Coulter, Animal chlamydioses and zoonotic implications. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 2003. 128(4): p. 217-244.

- 15Favaroni, A., et al., Pmp repertoires influence the different infectious potential of avian and mammalian Chlamydia psittaci strains. Frontiers in microbiology, 2021. 12: p. 656209.

- 16Mi, H., H. Li, and J. Yu, Psittacosis. Radiology of Infectious Diseases: Volume 2, 2015: p. 207-212.

- 17Mi, H., H. Li, and J. Yu, Psittacosis. Radiology of Infectious Diseases: Volume 2, 2015: p. 207-212.

- 18Nieuwenhuizen, A.A., et al., Laboratory methods for case finding in human psittacosis outbreaks: a systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2018. 18: p. 1-16.

- 19Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

- 20Kalim, F., et al., An overview of psittacosis. One Health Triad; Aguilar Marcellino, L., Younus, M., Khan, A., Saeed, NM, Abbas, RZ, Eds, 2023: p. 45-52.

- 21Li, X., et al., Clinical, radiological and pathological characteristics of moderate to fulminant psittacosis pneumonia. PLoS One, 2022. 17(7): p. e0270896.

- 22Chu, J., et al., Psittacosis. 2019.