Bladder Fistula is a pathological condition characterised by the formation of an abnormal connection between the urinary bladder and another organ or structure. This aberrant communication allows urine to leak into the adjacent organs from the bladder. This leak led to a variety of distressing clinical symptoms and significant morbidity. The common organ and anatomical structures include the bowel (enterovesical fistula), vagina (vesicovaginal fistula), or the colon (colovesical fistula). They are relatively rare, and their incidence increases with age and in populations with a high prevalence of pelvic surgeries. The aetiology of bladder fistula is diverse, and diagnosis involves a series of clinical evaluations, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. The management depends upon the underlying cause, location, and severity of the fistula. Bladder fistula represents a significant clinical challenge due to its varied presentation and impact on the patient’s well-being.

Types of Bladder Fistula

The types of bladder fistula are:

1) Enterovesical Fistula (EVF):

EVF characterises an abnormal connection between your bladder and the intestine. This type is uncommon but can result in substantial morbidity and may markedly affect your quality of life. Its incidence is estimated to be one in every 3000 surgical hospital admissions.1Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

Colovesical Fistula:

Colovesical fistula is the common subtype of EVF. It is frequently situated between the bladder dome and the sigmoid colon. The aetiology, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and management of colovesical fistulas are the same as those of EVF.2Seeras, K., et al., Colovesicular fistula. 2018.

Rectovesical Fistula (RVF)

A less common EVF subtype, RVF, is a communication between the rectum and the bladder. It is often linked to pelvic surgery, radiation therapy, Crohn’s disease, or rectal cancer.

2) Vesicovaginal Fistula:

It is an aberrant communication between the bladder and the vagina. It results in a constant leakage of urine through the vagina.3Malik, M.A., et al., Changing trends in the etiology and management of vesicovaginal fistula. International Journal of Urology, 2018. 25(1): p. 25-29. Its incidence is uncommon in developed countries, while it has a much higher prevalence in the underdeveloped parts of the world. At least three million women living in developing countries encounter the unrepaired vesicovaginal fistula. Due to obstructed labour, estimates suggest that 30,000 to 130,000 cases occur each year in Africa alone.4Medlen, H. and H. Barbier, Vesicovaginal fistula. 2020.

Ureterovaginal Fistula (UVF)

A subtype of VVF, this involves the ureter rather than the bladder connecting to the vagina. It usually results from surgical injury during gynecological procedures like hysterectomy.

Urethrovaginal Fistula

Another VVF subtype, this connects the urethra to the vagina and may result from obstetric trauma, catheter-related injury, or pelvic surgery.

Vesicouterine Fistula (VUF)

A rare variant of VVF, VUF is a connection between the bladder and uterus, most often occurring after cesarean sections or uterine surgeries.

Causes of Bladder Fistula

The causes of bladder fistula vary according to its type.

Causes of EVF

Colovesical fistula, the most common subtype of enterovesical fistula (EVF), has its own distinct set of causes. The following are the key causes of EVF, including those specific to colovesical fistula:

- Diverticulitis is the most common cause of a fistula. It refers to the inflammation or bulging of pouches (diverticula) in the wall of the large intestine. It accounts for approximately 65-79% of fistula cases.

- The possibility of developing EVF in the presence of Diverticulitis is between one and four percent.5Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- Abscess and phlegmon are subsequent risk factors in addition to diverticulum. They can contribute to the development of Fistulas by promoting localized inflammation and tissue erosion.

- Cancer is the second most common source of EVF in 10-20% of the cases.6Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- Crohn’s disease is another common cause of developing fistulas in 5-7% of cases of EVF.7Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

Besides CVF, other EVF causes include:

- Mackel’s diverticulum: A congenital outpouching in the small intestine, usually located in the ileum.

- Genitourinary coccidioidomycosis: A fungal infection caused by the fungus Coccidioides immitis.

- Pelvic actinomycosis: A rare but severe infection caused by the bacteria Actinomyces israelii.

- Appendicitis: An inflammation and infection in your appendix.

- Advanced-stage bladder and colon cancer can account for up to 1/5th of all cases.8Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- Lymphoma can also cause EVF, although it is rare.

Causes of VVF

Vesicovaginal fistula most commonly occurs due to gynecological or obstetrical injury. Its causes are classified into acquired and congenital forms.

Acquired Form:

Acquired form of the fistula can result due to the following reasons:

- Malignancy

- Radiations

The miscellaneous acquired causes include:

- Retroperitoneal surgery

- Pelvic surgery (Hysterectomy)

- Gynecologic and urologic instrumentation

- Sexual trauma

- Inflammatory and infectious diseases

- Vaginal laser procedures

- Vaginal foreign bodies

- External violence

Congenital Form:

The congenital form of vesicovaginal fistula is very rare and usually occurs in association with urogenital tract malformations.

However, in clinical practice—particularly in developing countries—fistulas often labeled as “congenital” are more accurately described as obstetric fistulas caused by prolonged obstructed labor and pressure necrosis. These are often seen in young women with limited access to proper obstetric care. Key risk factors in these cases include:

- Malnourishment

- Poor socioeconomic status

- Early marriage

- Childbearing

- Low literacy rates

- Inadequate obstetrical care

Symptoms of Bladder Fistula

Patients with enterovesical fistula, including colovesical fistula, often with the following lower urinary tract symptoms:

- Pneumaturia (passage of gas during urination)9Scozzari, G., A. Arezzo, and M. Morino, Enterovesical fistulas: diagnosis and management. Techniques in coloproctology, 2010. 14: p. 293-300.

- Fecaluria (presence of fecal matter in the urine)

- Frequent urination

- Urgency to urinate

- Hematuria (blood in urine)

- Suprapubic pain

- Recurring urinary tract infection (UTI)

Physical signs that may also accompany EVF include:

- Malodorous (very unpleasant-smelling) urine

- Debris in the urine

- Fever

- Abdominal pain

- Pelvic abscess (in more severe or chronic cases)

- Abdominal mass

In the case of vesicovaginal fistula, symptoms are more gynecological in nature and commonly include:

- Leaking urine in the vagina

- Changed the color and smell of the vaginal fluid

- Urinary incontinence or uncontrolled urine flow

- Vaginal irritation or discomfort (in some cases)

- Ureterovaginal fistula may cause flank pain, hydronephrosis, and urinary leakage without urge.

- Urethrovaginal fistula often leads to dribbling of urine, dysuria, and post-void leakage.

- Vesicouterine fistula may present with cyclical hematuria (menouria) and absence of vaginal bleeding (amenorrhea), especially if it develops after a cesarean section.

Diagnosis of Bladder Fistula

Diagnosing an EVF can pose a very significant task. To date, there is no agreement on a clear and precise gold standard for the workup of EVF. The diagnosis involves a combination of physical symptoms, imaging studies, and other diagnostic tests.

The diagnosis of this fistula type is based on the following steps:

History & Physical Examination:

The healthcare provider first considers the patient’s history on suspicion of a vesicovaginal fistula. Mostly, the cases are asymptomatic; however, symptom development following recent surgery is evaluated explicitly in symptomatic cases. The healthcare provider may ask you about the history of any cancer radiation, obstructed delivery, or trauma.

Pelvic examination under anesthesia is often paired with a dye test. In this test, the bladder is filled with a colored solution—such as indigo carmine, methylene blue, or sterile infant formula—and tampons or gauze sponges are placed in the vagina. If blue staining appears, it suggests leakage from the bladder into the vaginal canal, confirming a vesicovaginal fistula. Coughing during the test may help provoke leakage if not immediately visible.10Chen, Y.B., et al., Approach to ureterovaginal fistula: examining 13 years of experience. Urogynecology, 2019. 25(2): p. e7-e11.

The Poppy Seed Test:

It includes an oral intake of poppy seeds (50 grams) mixed in yoghurt or a beverage. Poppy seeds are not digested and should not appear in the urine under normal conditions. Their presence in urine within 48 hours strongly suggests communication between the bowel and bladder.11Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.12Kwon, E.O., et al., The poppy seed test for colovesical fistula: big bang, little bucks! The Journal of Urology, 2008. 179(4): p. 1425-1427.

Ultrasonography:

Ultrasonography helps in detecting the presence of the fistula. The yield of transabdominal ultrasonography is enhanced via abdominal compression. The ultrasonography discloses an echogenic ‘beak sign’—a classic indicator of EVF showing a tract between the bladder and bowel. It may also show gas or echogenic material in the bladder.13Sutijono, D., Point‐of‐Care Sonographic Diagnosis of an Enterovesical Fistula. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 2013. 32(5): p. 883-885.

Transvaginal ultrasonography visualises the exact size, location, and course of the fistula clearly. Transvaginal sonographic assessment carries a low side effect profile and is well-tolerated. However, their findings depend upon the skills and experience of the operator. Vaginoscopy aid in the visualisation of the opening of the fistula on the vaginal side. Vaginoscopy is an easy-to-perform and well-tolerated procedure.14Medlen, H. and H. Barbier, Vesicovaginal fistula. 2020.

Computed Tomography:

A CT scan is the imaging technique of choice for diagnosing EVF due to its high sensitivity. It provides more details about the fistula itself and also the surrounding tissues. The findings of the CT scan, which are suggestive of EVF, are:

- Air in the bladder (pneumaturia)

- Oral contrast medium in the bladder

- Thickening of the adjacent bowel and bladder walls

- Identification of diverticula or inflammatory masses

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is required in a subtle or difficult-to-diagnose fistula. It offers superior soft-tissue contrast, useful for identifying:

- Fluid-filled or air-filled fistulous tracts

- Associated inflammation or fibrosis

- Anatomical relationships with nearby sphincters and viscera

T1-weighted images and fat-suppressed sequences provide detailed structural insights.

Endoscopy:

Cystoscopy helps identify the site of the fistula. A small area of red, inflamed, in addition to elevated mucosa indicates a possible fistulous tract. Endoscopy also provides information about underlying diseases, such as Crohn’s disease or malignancy. Fistulas can also be an accidental finding during endoscopy performed for other reasons.15Shaydakov, M.E., A. Pastorino, and F. Tuma, Enterovesical fistula. 2018.

Treatment & Management of Bladder Fistula

Treatment and management of bladder fistula include the following approaches.

General Approaches:

The primary goal of treatment is to close the abnormal connection between the bladder and adjacent organs. The treatment strategy depends on the size, location, cause, and the patient’s overall health. If the underlying cause is treatable, it can aid in treating the condition.

Initial Steps:

Once the presence, size, and location of the fistula are confirmed through clinical examination and imaging, the first step is stabilization. Managing acute infections, such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), with antibiotics is also necessary. Temporary urinary catheterization can be used to divert the urine and reduce pressure on the fistula. Treatment of underlying medical conditions like diverticulitis and Crohn’s disease.

Conservative or Non-Surgical Management:

Conservative management involves treating symptoms and addressing any potential complications. Medical therapy includes antibiotics, steroids, total parenteral nutrition, bowel rest, and immunomodulatory drugs.16Yamamoto, T. and M.R. Keighley, Enterovesical fistulas complicating Crohn’s disease: clinicopathological features and management. International journal of colorectal disease, 2000. 15: p. 211-215.

- One common method is placing a transurethral Foley catheter for 2–8 weeks. This helps by continuously draining the bladder, reducing pressure, and allowing the fistula tract to heal. Anticholinergic medications can also be prescribed to reduce bladder spasms, urgency, and leakage, further minimizing irritation.

- Electrocoagulation of the mucosal layer around the fistula, followed by the placement of the transurethral catheter, can also help close the defect. Electrocoagulation involves gently cauterising the damaged mucosal tissue around the fistula to encourage healing. Afterwards, a catheter is placed through the urethra to keep the bladder drained. This process is called fulguration, which can be performed either vaginally or using a cystoscope (a small camera inserted into the bladder). It is a minimally invasive method for treating the fistula.

- Other conservative treatments, such as fibrin glue and other occlusive measures, involve non-operative trials to close the fistula, but they have limited success rates.

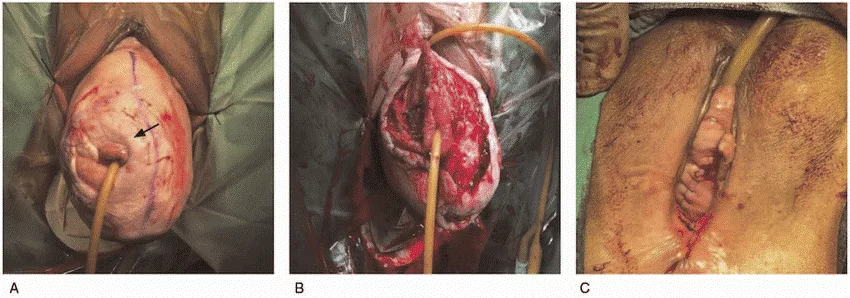

Surgical Approach:

If conservative management is unsuccessful, surgical intervention can be considered. This usually involves the removal of the damaged part of the bowel where the fistula is located. Sometimes, the surgeon uses tissue grafts from nearby areas to strengthen the repair. In conditions such as diverticular disease or mild Crohn’s disease, limited resection may be sufficient. In malignancy-related fistulas or radiation-induced damage, more extensive surgical removal may be necessary. Right after surgery, a catheter is kept in the bladder for a few weeks to help in healing the area.17Kaimakliotis, P., et al., A systematic review assessing medical treatment for rectovaginal and enterovesical fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2016. 50(9): p. 714-721.

Supportive Care:

- Surgeons perform cystography before removing the catheter to determine the integrity of the repair.

- They recommended pelvic rest for six to eight weeks postoperatively.

- Analgesics and stool softeners to reduce discomfort during recovery.

- Ongoing follow-up is needed to monitor for recurrence or complications, especially in patients with underlying malignancy or prior pelvic radiation.

Complications and Prognosis

Untreated and inadequately managed bladder fistula can lead to several complications, which include:

- Recurrent UTIs

- Abscess formation

- Skin breakdown or irritation

- Malignancy

- Electrolyte imbalance and dehydration

- Social and psychological impact

The prognosis for bladder fistula is generally very favourable when treated and managed in a timely manner. However, the prognosis can be less favorable in the following cases:

- Large or complex fistulas

- Poor general health

- Uncontrolled comorbidities

- Underlying malignancy and prior radiation therapy

Final Thought

Infections or surgical interventions can cause bladder fistulas. They cause an irregularity in the connection between the bladder and other organs, such as the bowel, vagina, and colon. The common symptoms include UTIs, urine that smells like stool, and gas that passes through the urethra. Changes in bowel habits, unexplained weight loss, and stomach pain are rare symptoms. Rush to your healthcare provider immediately if you experience any of these symptoms.

Refrences

- 1Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- 2Seeras, K., et al., Colovesicular fistula. 2018.

- 3Malik, M.A., et al., Changing trends in the etiology and management of vesicovaginal fistula. International Journal of Urology, 2018. 25(1): p. 25-29.

- 4Medlen, H. and H. Barbier, Vesicovaginal fistula. 2020.

- 5Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- 6Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- 7Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- 8Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- 9Scozzari, G., A. Arezzo, and M. Morino, Enterovesical fistulas: diagnosis and management. Techniques in coloproctology, 2010. 14: p. 293-300.

- 10Chen, Y.B., et al., Approach to ureterovaginal fistula: examining 13 years of experience. Urogynecology, 2019. 25(2): p. e7-e11.

- 11Golabek, T., et al., Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013. 2013(1): p. 617967.

- 12Kwon, E.O., et al., The poppy seed test for colovesical fistula: big bang, little bucks! The Journal of Urology, 2008. 179(4): p. 1425-1427.

- 13Sutijono, D., Point‐of‐Care Sonographic Diagnosis of an Enterovesical Fistula. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 2013. 32(5): p. 883-885.

- 14Medlen, H. and H. Barbier, Vesicovaginal fistula. 2020.

- 15Shaydakov, M.E., A. Pastorino, and F. Tuma, Enterovesical fistula. 2018.

- 16Yamamoto, T. and M.R. Keighley, Enterovesical fistulas complicating Crohn’s disease: clinicopathological features and management. International journal of colorectal disease, 2000. 15: p. 211-215.

- 17Kaimakliotis, P., et al., A systematic review assessing medical treatment for rectovaginal and enterovesical fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2016. 50(9): p. 714-721.